The statue of the slave trader is now on display in a museum, a year after it was pulled down by Black Lives Matter protesters

‘When people die, they enter history. When statues die, they enter art. This botany of death is what we call culture.’ The opening lines of Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet’s 1953 essay-film Les statues meurent aussi (Statues also die) – about African artworks in European museums – came to mind as the statue of slave trader Edward Colston fell in Bristol, UK, last year. As a warning.

Six and a half thousand weeks. Just under 125 years. However you measure the time that elapsed from that bleak November afternoon in 1895 when the statue was erected, what felt certain was that we learned something on 7 June 2020 when it fell. We learned that Colston was not immortalised. Or was he? He lived for 84 years as a man, for 174 years as a ghost, and then for 124 years as a monument. And yet four days later he was winched out of the water, and placed on loan with Bristol Museum. ‘The idea is at the moment just to stabilise him,’ the collections manager told the BBC documentary Statue Wars. When the ‘botany of death’ caught up with Colston, the museum interposed itself. Now the urgent question is: what is being stabilised?

Fallism – the grassroots practice of physically dismantling cultural infrastructure that promotes white supremacy – has been part of anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles since at least the early 1960s, when a ‘statue war’ broke out in Algeria at the moment of independence. The impulse towards preservation was also part of that history from the start. Back then, it operated as a kind of counter-insurgency. Algerians started defacing and destroying plaques and statues that commemorated colonial domination, making that domination and violence persist. The French military responded with a massive salvage operation. More than one hundred monuments were collected, shipped across the Mediterranean, and, as Alain Amato documented in his 1977 book Monuments en exil, re-installed in towns and cities across France. The Enlightenment maxim expressed by Diderot in 1795 hung in the air: ‘My friend, if we love truth more than the fine arts then let us pray to God for iconoclasts’.

Fast-forward to the footage of Colston falling, blindfolded, ropes slung around his shoulders and ankles, rolled along the street, drowned in the harbour, shared across the world. Like any image, and like the statue itself, and like Colston’s role in the enslavement of tens of thousands of African people, this is not a moment frozen in time; it’s still here in the present. Rewind to 1961 when Frantz Fanon described colonialism as ‘a world of statues’. In The Wretched of the Earth, he wrote how each statue never stops representing the exact same message: ‘We are here by the force of bayonets’. We learn from Fanon that every monument to anti-Black violence operates to re-inscribe that violence every day it remains on display. But is Colston still falling? Or did the museum break his fall?

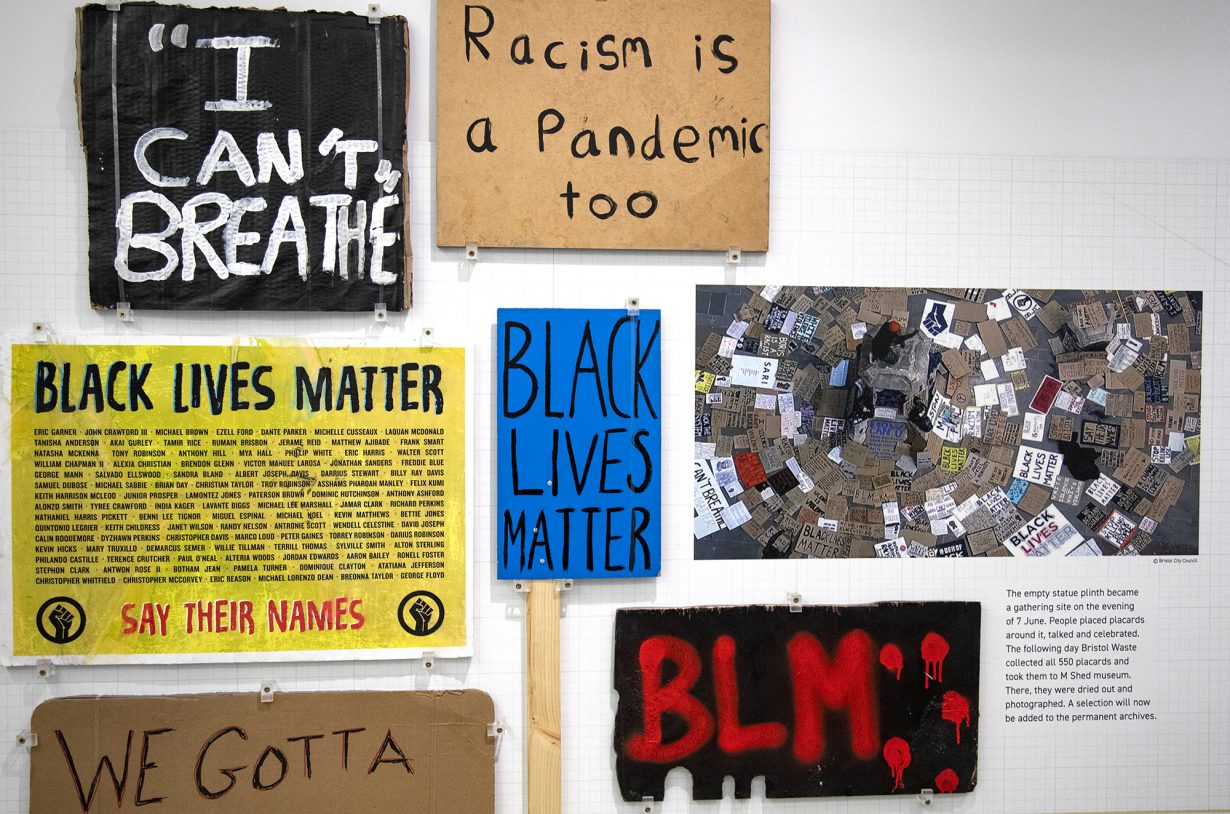

Last Friday afternoon I stood at the empty plinth at Magpie Park, between the traffic of Colston Avenue South and St Augustine’s Parade, a space created in 1892 by the culverting of the River Frome, suspended in paving slabs above the flow of water. I walked the short distance to Bristol’s M-Shed museum, retracing Colston’s short journey last year from one regime of display to another. In a corner of the museum there’s a window onto the city and the harbour and the light streams in. Laid flat, his height (now length) is a surprise – a monstrous 2.565 metres. Museum-goers queued up to gaze at his shoe-buckles, unbuttoned waistcoat, stockings gartered at the knee, hands sprayed red. His cane is still missing, rumoured to have been kept as a protestor’s memento. Sections of his coat are absent too; some bronze chunks perhaps remain in the harbour. A four-year-old boy exclaimed: “It’s that man from the video who fell over!” His dad replied: “Yes that’s right, but remember that he was pushed over”.

It’s not patina. It’s not just another layer in the life history of a Victorian statue. Fallism is removal. Fallism is the unfinished work of abolition. The inverse of conservation. And yet from the Houston Museum of African American Culture in Texas to the Anglo-Boer War Museum in Bloemfontein, South Africa to the Barbados Museum and Historical Society in Bridgetown, many monuments to white supremacy were removed from the streets to museums during 2020. The M-Shed exhibit is framed as ‘the start of a conversation’. The claim by the Telegraph’s art critic Alasdair Sooke that the display is ‘partisan’ is clearly wrong – the M-Shed exhibit is a carefully-curated exercise in balance and listening. But can any curated exhibition be a conversation? Would reclamation, retention, the preferred government ideology of ‘retain and explain’, the gesture of re-contextualizing and re-writing the label, always speak over – or erase – the voices of those who toppled Colston?

Last week in her opening comments for the panel ‘Beyond Museums in the Aftermath of Colston’, Sado Jirde, Director of the Black South West Network, observed that: “This work is really about reclaiming humanity, and we cannot do that in spaces that for so long were committed to dehumanising practices.” Her words chime with Sylvia Wynter’s critique of ‘monohumanism’, which is a critique of the universalist project of liberal humanism that statues like Colston’s embody. The statue is only on loan – it’s not yet accessioned. Its display reminds us that in Bristol and beyond the work of abolition is not over. The work of emancipation is not over. The work of compensation and repair is unfinished. The failure of public process over three decades to see the statue removed was a failure of our models of curatorial expertise, of public ‘engagement’, of authority. The fall remains unfinished.

Does Colston’s provisional preservation repeat the nostalgic counterinsurgency of the French army in Algeria? Or could it catalyse some new form of co-curation that destabilises the statue, and makes the fall rather than the man endure? For this to be possible, the very project of the museum would need to rebuilt from the ground up. But such a rebuilding might be possible at M-Shed if we recognise that the tearing down of Colston represents a new model for curation. This temporary display would be a positive first step in such a process. As someone who lived in Bristol for twelve years – first in in the 1970s and then in the 1990s-2000s – and like many who know this statue, I was moved to tears by visiting. Everyone who cares about racism, empire and slavery should see this exhibit. It should win awards. But that’s hardly the point. This is the kind of exhibit you come away from feeling that you can’t wait for it to be closed. I mean, the kind of exhibit that you come away from wishing to God it had never been necessary to create.

Should Colston now be venerated in the carceral spaces of the museum store for posterity? I’d prefer to see him returned to the bottom of the harbour, sunk forever into the Avon mud and forgotten. But whatever the fate of the statue, let’s keep Colston falling.

Dan Hicks is Professor of Contemporary Archaeology at the University of Oxford and Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum. He is the author of The Brutish Museums (Pluto Press).