From 2011: Vomiting, disjunctive memory, unapologetic pleasure, autobiographical narratives, romantic compulsivity – his work had the lot

I first encountered Marc Camille Chaimowicz in 1976, when he was a tutor and I was a student on the fine-art course at London’s Hornsey College of Art. All the art-school constants applied here: men were proud and virile, and alcohol was drunk and vomited in a year’s recommended-units-per-person each evening. Students wore paint-splattered trousers. Although 1970s feminism was on the move, women were underrepresented as tutors and overrepresented as the objects of sexual attention. Thus did the students and staff of this educational paradise go about the theory and practice of art: by getting smashed and copulating. Oh, and 1970s art was often stern. It was radical and tough and rigorous and committed, as if things weren’t bad enough already.

Chaimowicz was not really of this masculinist world. His was a wandering presence, on the margins but not marginalised. He was, whether amused or appalled by things, unfailingly courteous and affirming. I’m flattered that he remembers more of my degree show than I do. His expressions of interest were made in intonations of great particularity and exactitude that perhaps relate to narratives in his work to do with the restoration of grace to circumstances of difficulty or impoverishment. He was born in Paris in 1947 to a Polish-Jewish father and a French-Catholic mother, and came to England when he was eight. Perhaps these experiences contributed to a heightened awareness of identity, stigma, memory and recall, exclusion and extreme loss, and the enormity of importance that ceremonial ritual has to human meaning in such circumstances.

Chaimowicz makes furniture, sculpture, painting (including a 2003 chapel ceiling at the Hôtel-Dieu de Cluny, in France), drawing, collage, photography, ceramics and craft objects. He creates installations and performances, rugs, folding screens, wallpaper and videos, and writes. He has worked with tape and slide. Characteristic forms are the panels he makes, which are tiled against walls and are analogous to the recalls of conjunctive or disjunctive memory, a principal theme. Stylistically there is an interest in pastel colours, pattern, decor, design forms, texture and fabric material. There is a strong French emphasis, especially a literary one. And there is an unapologetic pleasure in popular music.

The arrival of punk to Hornsey in 1976 was of little interest to other tutors. Chaimowicz, though, had a prescience and curiosity about his students’ early punk endeavours, probably related to the use of music in his own work and our shared interest in gender adventure. Literal and metaphorical themes of overlap, especially of gender, have remained constants in his work. Our preferred music included the Raincoats and the Slits, both all-female groups who, like Chaimowicz’s favoured Bowie, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Kinks, the Velvet Underground and glam rock, were inclined to forms of gender mischief. Ana da Silva and Gina Birch formed the Raincoats at Hornsey, and the early Slits had a strong Hornsey association as well. The Raincoats’s 1979 all-female version of the Kinks’s transvestic Lola (1970) represented a shared generational interest in gender subversion.

Chaimowicz’s best-known work is the 1972 installation entitled Celebration? Real Life, first shown at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, but finding its most effective early form at Sigi Krauss’s Gallery House, London, later that same year. Reconstructed in different versions between 2000 and 2002 and entitled Celebration? Real Life Revisited, it comprised, or comprises, a carefully arranged assemblage of disparate found objects, documentary material and souvenir kitsch: masks, a bra, a discarded female shoe, tinsel and glitter, religious statuary, a handbag, some deco vases and other items – the reconstructions containing largely similar but not always identical objects. There are intimations of the autobiographical in the selections.

In all versions, objects are placed or strewn or arranged on the floor in a darkened space, but in Gallery House the darkness was that of an architecturally imposing, prestigious ‘ballroom’. The tessellated mirrors of several disco balls refract light onto the work from strobe lights, fairy lights and spotlights, and via revolving theatrical colour wheels, recalling the LSD-associated moods of 1960s light shows, disco environments and happenings. The work has a full-on sonic appeal courtesy of Bowie and the bands already mentioned, whose music is played as part of it: chosen, it seems, for pure pleasure rather than theory. Looking at photographs of the piece without the music is almost meaningless. (For those who haven’t seen it, YouTube is the next best place to gain understanding of it.) The work is floor-based, and standing above it can be likened to being a passenger in an aircraft coming in to land over an exciting cityscape at night, the fairy lights on the floor like a highway serving a metropolis with vast romantic and sexual potentiality. (I experienced similar ideas of aerial eroticism on seeing the rugs that Chaimowicz designed and presented, suspended high in the air, at his 2010 show at Bloomberg SPACE, London.)

In 1972 these musicians lacked the dense drag of history they’ve now accrued, and their music was regarded as immediate, untheorised and sexually uncontained, and as culturally contesting. Mostly mascarawearing males, they had a very different outlook to the non-mascarawearing males of 1970s radical UK art, who although often engaged in contesting cultural values – especially from leftist positions – were perceived as practising narrow orthodoxies: overtheorised and disapproving of pleasure and certainly of transgressive sexuality. The original Celebration? implied socialised sexual pleasure; some of its object forms, and the disco idea itself, invoked gender themes. Discos in the 1970s were a sympathetic environment for gays and women, who otherwise lacked public recreational spaces in which to feel safe.

I saw (unless it was a dream, which it might have been) the 1972 Celebration? at Gallery House as a lone sixteen-year-old truant, wandering around London, probably stoned. Gallery House was situated in a grand building, temporarily available for art exhibitions courtesy of the German Institute, but which felt more like a squat. It had a trashed interior, in which the exhibiting artists – in this case Chaimowicz, Stuart Brisley and Gustav Metzger – enjoyed 24-hour occupancy. My experience of the art and the gallery was as an exciting, anarchic trespass. The house implied wealth, power and exclusivity, and the art implied impoverishment, reempowerment and inclusivity.

I have only a dim understanding of how far my memory of Celebration? is based on having seen it, or on later documentation of it or its reconstructions. I saw it without its lights and music – probably present at a strange hour, a bit frightened, peering into twilight rooms. Chaimowicz, who was usually there to welcome guests, was not present. His presence was part of the work: to make tea for visitors and engage them in discourse. Without lights and music or Chaimowicz, the work had a different existence, its psychedelic energy changed to that of a disturbed, post-trip comedown. I was regrettably experienced in such LSD matters. It was like disturbing a ritual grave in which incomprehensible things had been interred a thousand years earlier, and which, about 500 years later, had been rudely ransacked. Or as I said, maybe I wasn’t even there – maybe it was all a stoned misunderstanding.

Celebration? Real Life Revisited was first shown at London’s Cabinet Gallery in 2000 and then in a number of museum shows up until 2002. Its display principles have remained constant, but its meanings have changed by virtue of being consciously reconstructed, with many theoretical issues in attendance – the new versions are not so ritually correct as to try and prevent new meanings, but in fact embrace them.

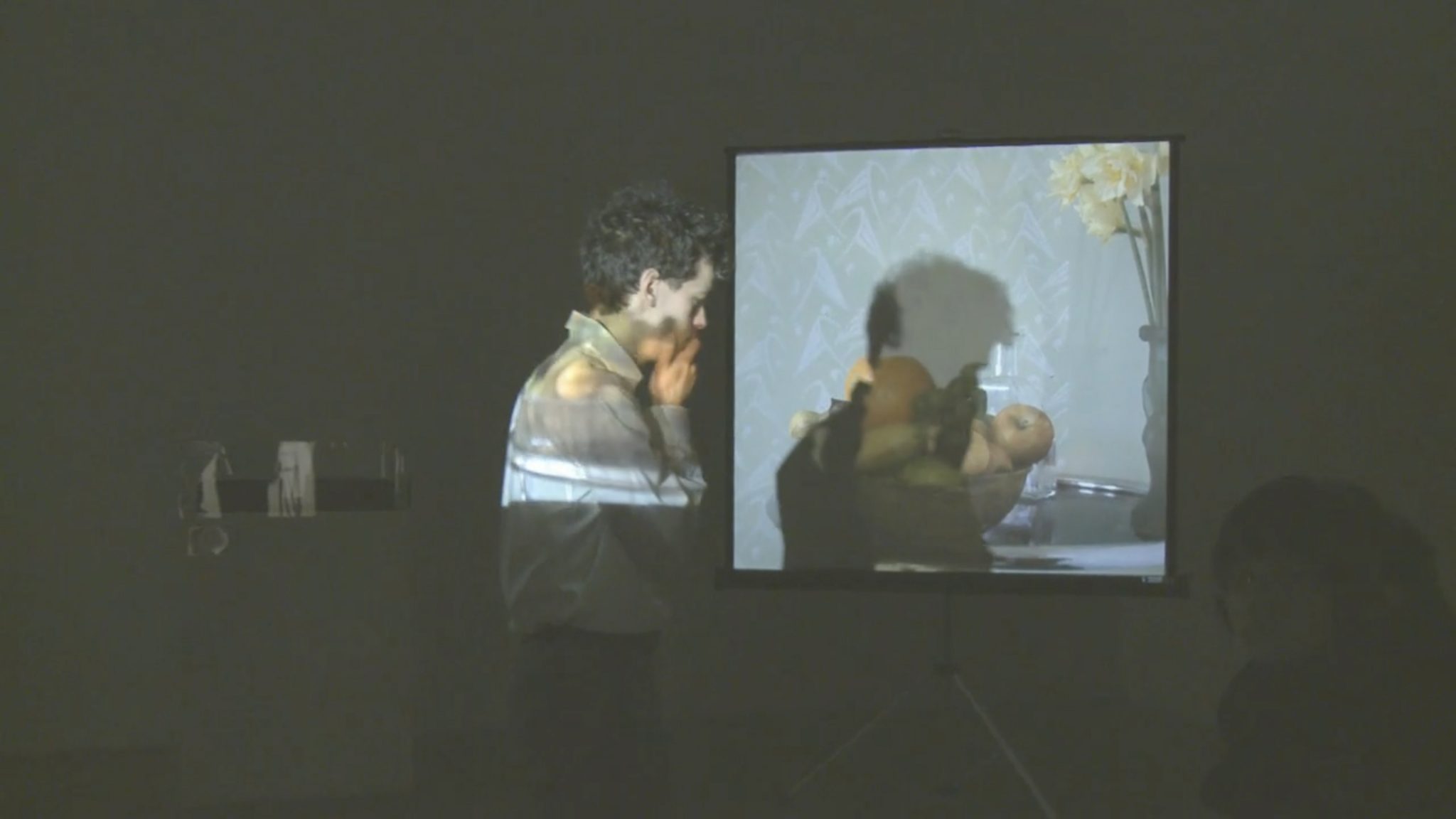

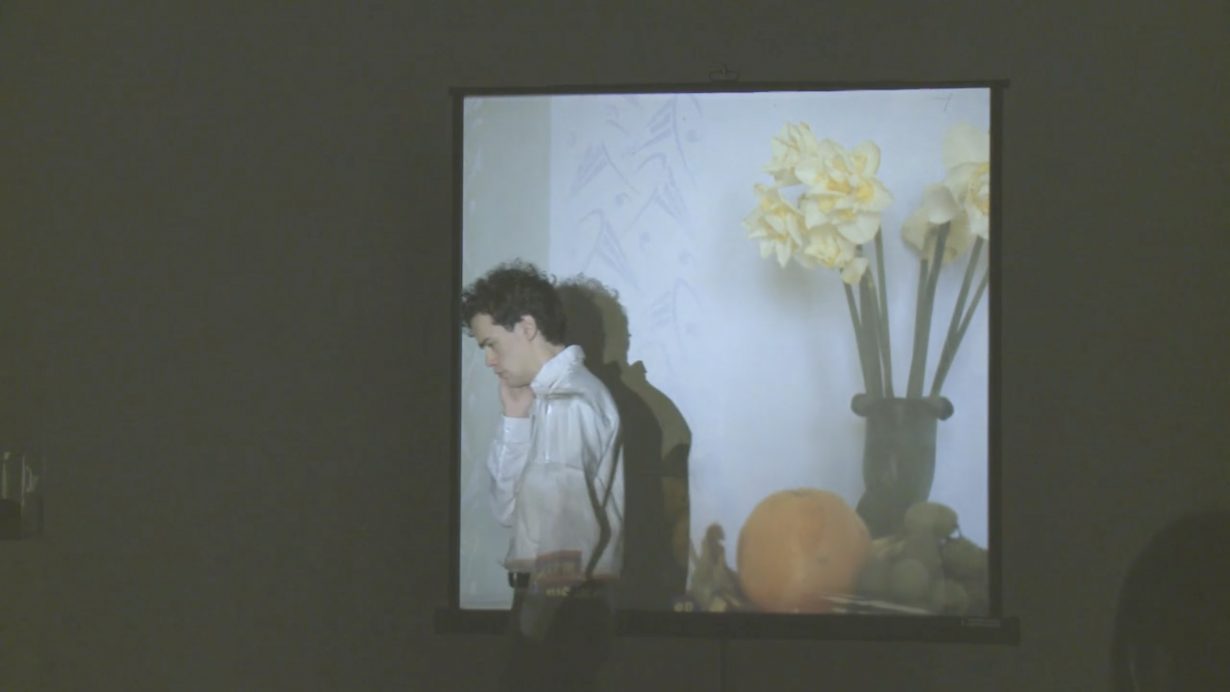

Chaimowicz’s performance and installation work Partial Eclipse… (1980–2006) also exists as a revisited form, and is currently installed at Tate Britain. This work exemplifies the artist’s interest in the interrelatedness of human maleness and human femaleness, and of text and image, through poeticised, hyphenating, possibly autobiographical narratives. In the performance a suited Chaimowicz (at Tate this is not Chaimowicz himself, but a good stand-in) conspicuously wanders in front of – overlapping with, and casting his shadow upon – a monochrome slideshow, in which he and what appears to be a boy-girl in men’s clothing are cropped and edited so as to create a confusion between their physical selves, in a kind of gender melding. At Tate, the work is presented as an installation of photographs and texts that document the original 1980 work.

It was, I remember, always a pleasure to go to openings at the Nigel Greenwood gallery between the 1970s and the beginning of the 1990s, where Chaimowicz was represented, although there was no one-person show in the UK for him for the whole of the 90s. His career has been sometimes fashionable, and sometimes less fashionable, but he has always been active, and in the 90s he showed in countries with less YBA-orientated orthodoxies. This period includes very un-YBA pencil and gouache works on paper, such as Series 1 No. 4, London, August (1996).

In recent shows, such as a solo exhibition at Edinburgh’s Inverleith House (2010), a group show, Polytechnic (2010), at Raven Row in London and the current Jean Genet… The Courtesy of Objects, at Nottingham Contemporary, where Chaimowicz has curated guest works by Alberto Giacometti, Tariq Alvi, Lukas Duwenhogger, Mathilde Rachet and Wolfgang Tillmans, Chaimowicz’s various images and object forms appear and disappear in a kind of discourse. He invites artists, both living and dead, to contribute their work to meta-curations of his and their artworks, or includes evidences of them, such as their catalogues. As well as the artists already mentioned, these included Richard Artschwager, Tom Burr, Michael Krebber, Giacometti, Warhol, Tom of Finland, Cerith Wyn Evans, Marie Laurencin and Enrico David.

Jean Genet… The Courtesy of Objects makes reference to the French writer’s celebrated play The Maids (1947), a super-intense fusioning of female sexual identity and power. The installation Props and Wardrobe Room (2011) and film The Casting for ‘The Maids’: First Cut (2010) are potent dramas of this gender theme, and seem simultaneously confessional, historical and deeply private. Props is a collection of objects – vintage dresses, women’s shoes – in a room structure that can only be viewed from without. Men’s ties hang among the dresses. The images in Casting flash up in an impressionistic style, showing female servants interacting with Chaimowicz, creating implications that he might correspond in some way to the mistress of Genet’s original.

Chaimowicz’s work, then and now, is replete with gay and heterosexual signage, but lacks a clear sexual and romantic rulebook. It is a world that contains tender love and affection, as well as being an introspective place with seeming narratives of complicated sexuality: of bisexual transvestism, fabulously ritualised autoerotic narcissism such as Dressed & Undressed: Coiffeuse (peut-être pour adolescents) (2008, a dressing-table work with all-important mirror, and female garments as if liberating themselves from a drawer), codependent romantic compulsivity and triangulating erotic ménage. (There is much documentation of third-party couples, with photographs depicting them arranged on decorative screens.) There are also the melancholies of unrequited love, and vacillations between romantic isolation and acceptance of loss. It is obsessive work about associative memory, recall and fantasy, in which fur, flowers, fashion and fabric materials are revered or fetishised in shrine constructions, for example Assortment of Items for ‘The Maids’ (2010–11).

Femininity is accorded a worshipful absoluteness in all this. It is defined not only by the ongoing certitudes of prescriptive femaleness – pale ‘feminine’ colours (lilac, mint green, peach), the perfumed boudoir, lack of autonomy and exclusion, domesticity and romantic love – but also by ideas of mothering such as Here and There (1978), in which Chaimowicz is seen applying makeup, below some photographs of idealised motherhood. And there are some not-so-central ideas of female sexuality to be considered. If there is any penetrating going on, it is (theoretically) as likely for females to be penetrating males, using their best imaginative abilities, as any other variation, as intimated in Partial Eclipse… This may be a challenge for those gays and straights who prefer the usual certainties of their respective mainstreams. The work also contains an aspect of sexuality usually perceived as embarrassing, whether gay, straight or deviant other: celibacy. Chaimowicz’s work, both now and in the past, offers many remembrances of absent love objects, which are cast as interrupted, disallowed or just not enacted – a meditative, sexual ceasing. Many works, both visual and textual, including his book Café du Reve (1985), show or describe Chaimowicz exercising choices of solitude or isolation, often looking out a window, or writing to an absent lover, creating moods of reflective absence.

It would be appropriate to end with a strong focus on Chaimowicz’s most recent work – his Nottingham show, or upcoming shows in Berlin, Frankfurt and Chicago. But, in the best of senses, there isn’t any new work. It’s all one very large, interrelated work endeavour: a singular project that is a lifetime’s process of growth and regrowth, becoming cumulatively richer in meaning over time.

This article was first published in ArtReview September 2011