New year, new you: ArtReview’s editors on the best of contemporary art in January 2023

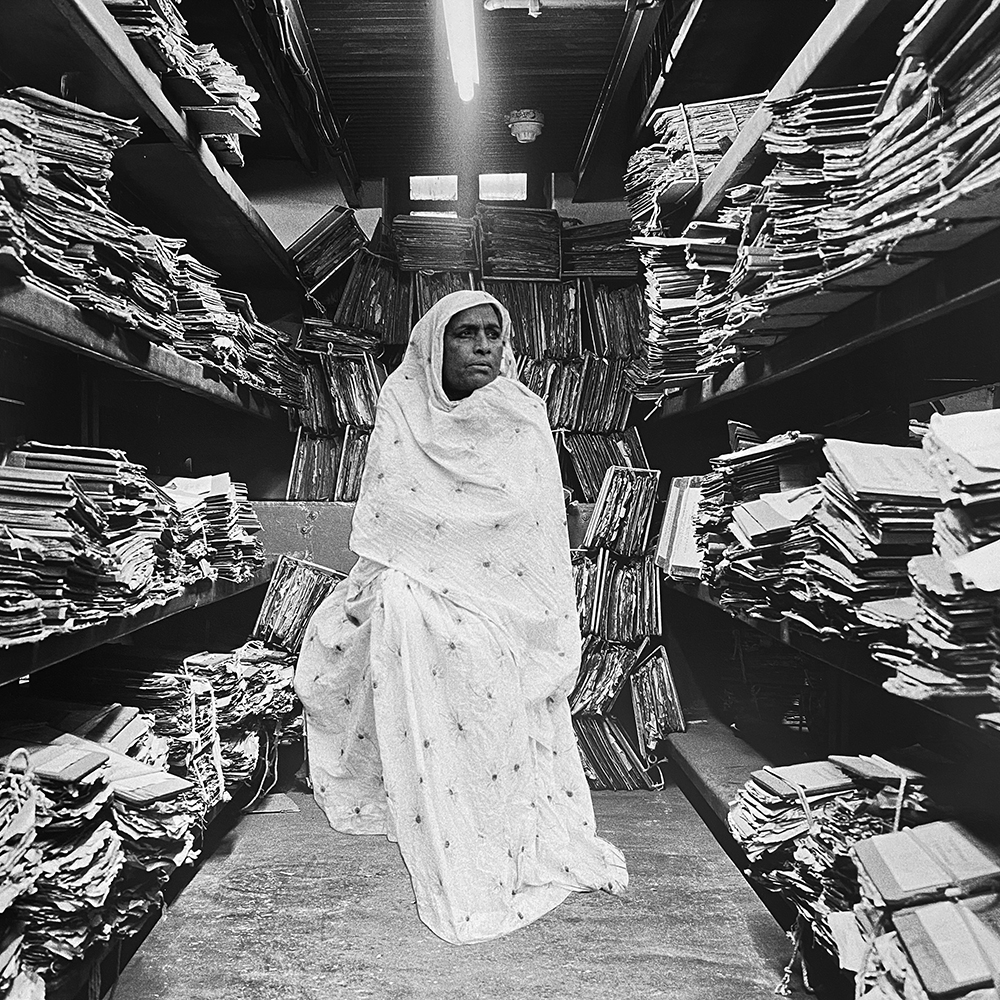

Dayanita Singh

Hasselblad Center, Göteborg, through 22 January

For nearly four decades Dayanita Singh has been bending the rules of how photography can be presented – and by extension, experienced – by blending book publishing, archival practices and museum display. You won’t find her photographs (of architecture and interiors, the artist’s childhood, music sessions, portraits of her late close friend Mona and, of course, archives) printed and mounted on walls in any conventional manner. Instead you’ll find them bound in little books that fit into the many pockets of a bespoke coat (My Life as a Museum, 2018); or in various series printed on card and housed in a handmade wooden box with a cutout window, so that each image may be displayed one at a time (when multiple boxes are placed side by side, the combinations are innumerable); or in the form of Singh’s portable ‘museums’ – installations of modular wooden structures that display the photos and which can be altered and reorganised, and are therefore everchanging. So it’s no wonder that Singh has won the 2022 Hasselblad Award (the first South Asian photographer to do so), part of which means she’ll be presenting an exhibition, Sea of Files, of works spanning her career. Fi Churchman

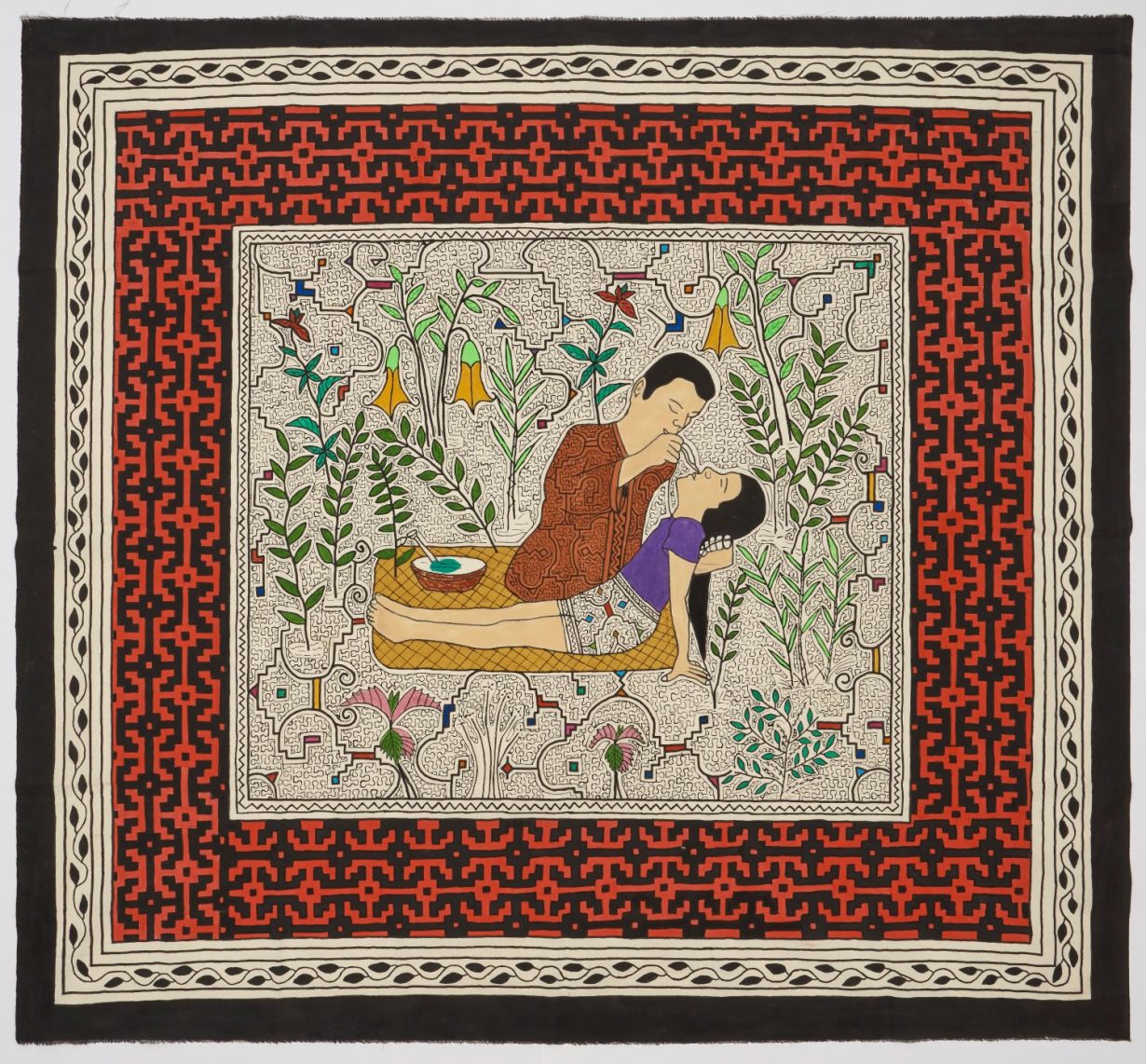

Mothers, Plants And Women Fighters: Visions From Cantagallo

MAC Lima, through 26 February

Cantagallo is a rabbit warren of makeshift shacks and shop fronts that has grown up on the site of a former landfill in Lima, a favela community sandwiched between a busy motorway and the Rímac River in the Peruvian capital. It is home to Shipibo indigenous families uprooted from their original Amazon lands two decades ago by logging. It was also a COVID-19 hot spot during the pandemic, registering at one point in 2021 three deaths and seven infections to every ten inhabitants. The area was put into isolation by the Peruvian authorities, with no one allowed to enter and no one allowed to leave, an imprisonment guarded by around two hundred soldiers. Under these conditions, mental as much as physical health deteriorated. Step forward resident Olinda Silvano, who works with Kené, an ancestral art formed through ayahuasca visions. As the virus waned, she conceived of an arts centre that would raise morale and allow the people of Cantagallo to both reconnect with each other and the outside world. The result was hundreds of works, including paintings on fabrics dyed with mahogany bark, paintings on canvas, embroideries, collages with fabric, made by 29 women who became known as the Non Shinanbo (‘Our Inspirations’) collective. Typically each work shows a central figurative scene – images of care and sickness, loss and isolation understandably dominate – against an incredibly intricate patterned background and framed by an equally complex geometric abstraction. This show surveys the fruits of that regenerative labour to a wider audience. Oliver Basciano

Mohammed Sami: The Point 0

Camden Art Centre, London, 27 January – 28 May

Trauma lurks beneath the canvases of Mohammed Sami. In fact, some of the interiors conjured in the Iraqi artist’s paintings look like scenes of unidentified crimes. Deserted by human figures, they are haunted by the presence of details that, under his brush, register as disquieting clues in otherwise banal domestic settings: a broken pot; a candlestick phone hanging from its chord; a half-popped blister pack of unspecified medication; red stains on a carpet; or the long shadow of a door. The ambivalent, unnerving character of these paintings stems from Sami’s own memories of growing up in Baghdad under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship (the artist moved to Sweden in 2007 as a refugee) as well as from a ‘delusive strategy’ he interiorised during his time Iraq, as he told The Guardian this year, ‘to not let the authorities understand what we’re saying’. But whether or not you’re privy to the memories doesn’t really matter, for their presence and materiality will stick with you long after you’ve left them. Louise Darblay

Karrabing Film Collective: Wonderland

Haus der Kunst, Munich, 27 January – 30 July 2023

Beginning a promising 2023 calendar for Munich’s Haus der Kunst, Karrabing Film Collective’s ‘first major museum survey’ – curated by Damian Lentini with Anne Pfautsch – will present all of the predominantly-Indigenous Australian collective’s ‘major’ films. Perhaps the most effective recent miners of the much-cited ‘intersection’ of fact and fiction, Karrabing have become increasingly adept at manipulating form – often shooting stories of astral and ancestral beings with phone cameras, or concealing stories driven by frustration and anger within mockumentaries of manipulated footage – to recover control over Indigenous narratives. A busy 2021, with shows at NYU Shanghai’s ICA, Kunstverein Brauschweig and E-Werk Luckenwalde, gave way to a quieter 2022 dotted with biennale features but focused predominantly on community projects. This year, Wonderland opens before a spring show at Secession in Vienna. Alexander Leissle

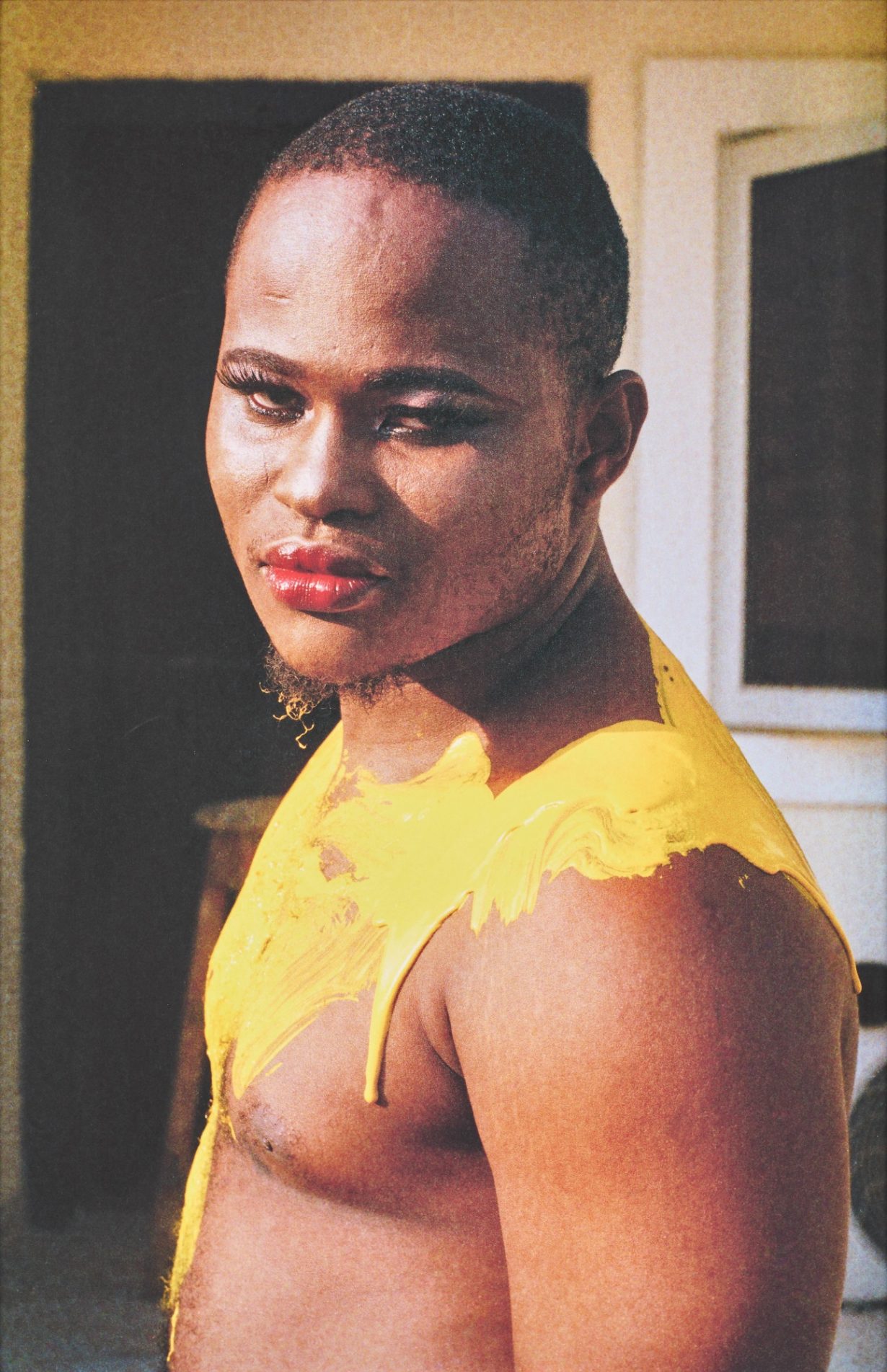

A Different Now is Close Enough to Exhale on You

Goodman Gallery: Johannesburg, through 14 January; Cape Town, through 21 January

This group show in three parts (at both South African Goodman Galleries with a satellite show of photographs at Umhlabathi Collective in Johannesburg) – curated by incoming director of Berlin’s HKW, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung – can scarcely be accused of narrow scope or miserly ambition, with dozens of artists on display across two cities and exhibition notes listing broadly-outlined themes of ‘power, extraction and exploitation… resilience, defiance and communion’. Transition, though, is its unifying force: apartheid lives almost thirty years in the memory while bearing a spectral – and tangible – presence in the country; the image of South Africans’ struggles as a kind of proxy movement for many other African nations is morphing into something harder to parse; colliding forces of oppression by conquest and the ever-mounting climate emergency pile new challenges and ruptures upon the preexisting, across multiple nations. Sabelo Mlangeni’s by turns convivial and radical photographs, Danielle McKinney’s subtly enigmatic portraits, and Keli Safia Maksud’s musical topographies are but a few to take up these conceptual challenges – and should not be missed. Alexander Leissle

Lawrence Lek: Nepenthe (Summer Palace Ruins)

QUAD, Derby, UK, through 5 February 2023

Lawrence Lek’s Nepenthe Valley series stitches together ancient and future time in an uncanny virtual setting, created via the Unreal video game engine – its title a reference to the myth of Nepenthe, a drug of forgetting. In Lek’s videogame worlds, the artist explores the effects that liminal spaces have on memory, as we float (RPG-style) through their ambient spaces: ‘an experiment’, Venus Lau wrote recently, ‘for a futuristic mnemonic mechanism.’ This particular edition – an installation and playable game – pivots around the ruins of Yuanmingyuan, the Qing imperial retreat in Beijing which was flattened by British and French troops in 1860, and has since become a site for patriotic and moral instruction and the focus of debates over Chinese national memory. En Liang Khong

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley and Josèfa Ntjam

FACT, Liverpool, through 9 April 2023

Speaking of videogames, over at FACT in Liverpool, an exhibition of artists Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley and Josèfa Ntjam – part of the gallery’s ‘Radical Ancestry’ series unpicking ideas of belonging and identity – spans non-Western histories of resistance, mapmaking, and games in order to craft new speculative fictions and chart transformative futures. For Ntjam, this takes the form of a cosmic, subterranean cavern, teeming with jellyfish and mushrooms, a cipher for ‘how spaces of solidarity, care and revolution can thrive in darkness.’ While Brathwaite-Shirley – an artist who has fused game design and exhibition-making in a vivid, urgently political mode(players of her games in the past have been urged to consider Black trans experiences) works with a group of young people from the local area, bringing their visions and perspectives to bear on the creation of a new videogame, played online and in the gallery. En Liang Khong

Johanna Hedva: Who Listens and Learns

Modern Art Oxford, through 5 March 2023

‘I was raised by witches, which means that the dead were very much alive in our house,’ Johanna Hedva told ArtReview’s Ross Simonini in 2020. ‘They spoke constantly, and their language was tricky and multilingual, but they rarely spoke directly to you in a language you could understand.’ In a new installation at Modern Art Oxford (as well as available online), the Korean-American musician, writer and artist weaves together such attentiveness to language, vocalisation and mysticism via a short story, in which we meet two characters: Coconut the AI-Enhanced Virtual Companion and the Woman Who Carves the Tree. The story is told both through the medium of an AI vocal clone (the artist has attempted to ‘deceive’ the speech software by training it through their own voice, which has itself been altered through various synthetic procedures), as well as a handmade book featuring human hair and ink drawings. It’s a meeting of the worlds of AI and the supernatural, speech and narrative experimentation, typical of the artist’s interests. En Liang Khong

Andrea Fraser

Marian Goodman, New York, 12 January – 25 February

Fraser has for more than three decades made the artworld’s institutional politics – its power hierarchies, hypocrisies and blindspots – the subject of her work. That she takes these subjects on with a kind of maniacal humour and personal investment – in performances in which she impersonates the artworld’s personnel and ventriloquises its discourses – is perhaps why she has managed to stay visible, hard to exclude and ignore. This first show with Marian Goodman offers an chance to see old and new works, from the 1991 Welcome to the Wadsworth: A Museum Tour (in which Fraser hijacks the conventional museum-guide format to focus on the history of the titular museum) to her most recent video-performance This meeting is being recorded (2021). In this latest work, the question of institutional power and the individual’s involvement in it takes on race politics post-BLM; Fraser plays the roles of six white women, a group with whom she worked in 2020, bringing psychoanalytic methods to bear on the issue of internalised racism, reperforming their fraught and often stressed examination of their own relationship to power and inequality in contemporary America. J.J. Charlesworth

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck

In theatres and on demand from 4 January

I’m not really one for making New Year’s resolutions. The idea of submitting to some new fad diet appals me, I’m not giving up alcohol or caffeine (ie, coping mechanisms) during one of the bleakest months of the year, nor am I willing to start practising ‘mindfulness’ because what I really want is to do less of the thinking and feeling. (There are of course more noble pursuits, but if you have to use the framework of a ‘resolution’ in order to carry out good deeds, then, well, I feel sad for you.) Perhaps Mark Manson’s self-help-book-turned-movie will be the perfect tonic to my new-found love of mezcal. “You’re going to die one day,” says Manson in the film’s trailer. “I just wanted to remind you… you deserve to be special, unique and extraordinary. Actually, that’s bullshit.” In this new film format, Manson explores humans’ fixation on finding happiness and how (Western) society dictates what exactly that is via what’s promised to be a series of humorous anecdotes. Alongside a character called Disappointment Panda (based on that gif where a panda-suited man smashes a computer), who has no qualms about telling people ‘the hard truth’ about life. Who knows, maybe I should just enjoy my mezcal neat. Fi Churchman