Rather than acknowledge or exorcise the ghosts of previous scandals surrounding the 2019 Triennale, Still Alive twists around to gnaw on its tail

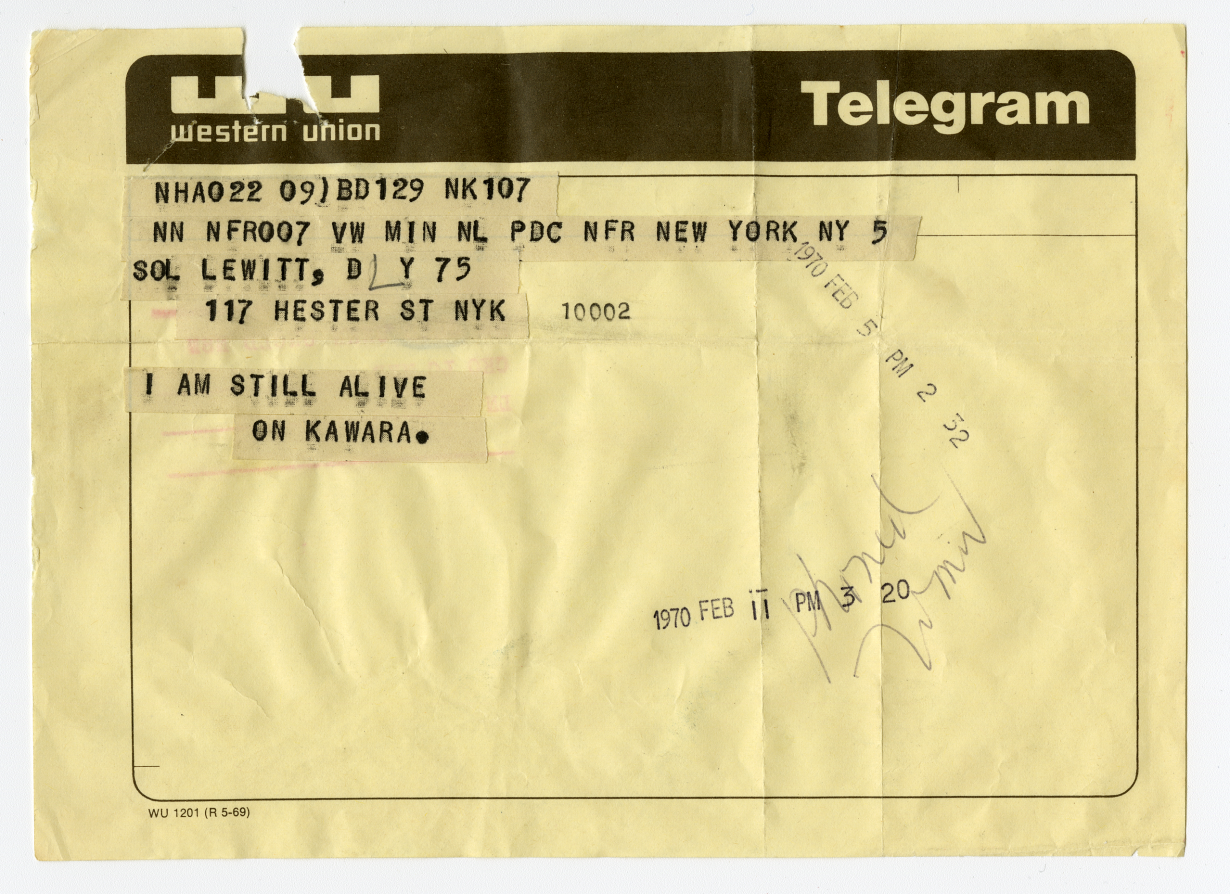

The words in the title of this year’s Aichi Triennale – ‘Still Alive’ – come from the output of a dead man. And the irony – conscious or unconscious – rings through the exhibition as a whole. But we’ll come to that later. More specifically, the words are borrowed from On Kawara (who died in 2014), and the series of telegrams (eventually numbering almost 900) containing the declaration ‘I Am Still Alive’ that the Aichi-born artist initiated in 1970. They form the initial display of the triennale’s main exhibition at the Aichi Arts Center in the prefecture’s capital, Nagoya City, where a selection of the telegrams, individually mounted and framed, are displayed in spotlit, glass-topped cabinets. Like precious relics.

It’s at once meaningful and monotonous; an archive; the trace of a life (and, like much of the artist’s output, a meditation on time); and a display of both presence and absence (Kawara himself, who eschewed public appearances and began the I Am Still Alive series with telegrams sent as a contribution to a Paris exhibition reassuring the curator that he was still alive and did not intend to commit suicide). Collectively they form something of a map (the outlines of which are given by the various formats offered by the places from which they were sent) and

a chant. While the first chimes with Marcel Broodthaers’s Carte d’une utopie politique et petits tableaux 1 ou 0 (1973 – a political world map with the word ‘world’ crossed out and replaced by ‘utopia’) that forms a type of foreword to Kawara’s work, the second echoes though the remainder of the Arts Center display. Through Korean-American Byron Kim’s diaristic Sunday Paintings (2001–), capturing clouds in the sky on Sundays (those here executed during 2020–21 – the covid era), each containing a brief hand-written summary of his thoughts and feelings on the day: commentary about the weather, the wellbeing of friends and family, the spread of the virus. And through Fukushima-based Wago Ryoichi’s Pebbles of Poetry (2011–22), a series of poems – in the form of epistemic and existentialist musings posted on Twitter – begun in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, extended during the COVID-19 emergency and internationalised earlier this year in collaboration with Kharkiv-based artist Olia Fedorova. And through Roman Ondak’s sliced tree trunk, Event Horizon (2016): 100 pieces of wood stamped with the years between 1917 and 2016 (corresponding to the rings in the trunk) and a historical event from that year. And, more obviously and subversively, in Zimbabwean painter Misheck Masamvu’s Still Still (2012–22), a video about (and the sliced-off side of) a white Volkswagen Kombi bus with slogans such as ‘Still hiding’, ‘Still held in prison’, ‘Still in a hole’ and ‘Still waiting’ stencilled onto its surface. To which, in the context of the exhibition as a whole at this point, you might be tempted to add ‘still stuck in a rut’. Although others would say this is a ‘tightly curated’ show.

With that in mind, the words ‘Still Alive’ might also be read as an acknowledgement of the triennale’s endurance following the scandals surrounding censorship in 2019 (of a sculpture display that referenced the plight of ‘comfort women’ – women from occupied countries forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese during the Second World War). And yet, overall, despite both that and the centrality of a dead man, this is not an exhibition about ghosts or the exorcism of them. Though perhaps it should be.

Of course, as you will have gathered by now, the phrase ‘Still Alive’ is also a reference to the pandemic era in which this exhibition was conceived and executed by artistic director Mami Kataoka (also director of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo) and a curatorium of nine advisers, spanning Rhana Devenport (director of the Art Gallery of South Australia) through to Victoria Noorthoorn (director of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires), who suggested artists to fit the theme, given that travelling to see them was not an option. Under the still-being-alive rubric, the exhibition, which features work by 82 artists and 11 performance groups as well as an extensive education programme, also explores issues relating to health, racism, indigeneity, artificial intelligence, migration, gender and ecology.

But perhaps this form of control, in which the exhibition twists around to gnaw on its tail, also introduces questions about what museums are, or are for (Katoaka is also the current director of the museum association CIMAM). Not least because the remainder of the Triennale takes place in a series of offsite presentations spread across sites in the wider prefecture, namely Ichinomiya (one of Japan’s ‘textile capitals’), Tokoname (known for its pottery) and Arimatsu (situated along a historically preserved road in Nagoya’s suburbs). Places where people still live, and go about their daily lives. After you’ve seen Theaster Gates’s contribution, The Listening House, a reactivated and redesigned residence at Tokoname (where the Chicago-based artist studied ceramics during a residency in 1999 and has periodically returned ever since), which has been transformed into a studio, workshop and club-type social space (complete with turntables and a collection of Black soul and jazz records), you get the feeling that ‘alive’ means something different outside the museum. The records were bought from a now-dead friend: the ceramicist Marva Jolly. The work celebrates the conversations and social relations between artists, rather than merely their formal relationships, and consequently is a space in which the visitor is welcomed as more than just a viewer.

Similarly, Anne Imhof ’s Jester (2022) a two-(jumbo-)screen videowork documenting a performance (a drummer and dancers) that took place during her solo exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo last year, is screened in an ice rink (without the ice) in Ichinomiya. The sound is loud (so loud, apparently, that the neighbours complained after the first day) and echoes round the rink; the dancers move together and apart, seemingly at once spontaneously and rehearsed. It’s a raw, at times animal form of conversation. Something that doesn’t quite fit with the refined and genteel space of the museum galleries, and something, in the context of your imaginary of what’s normally going on at a public ice rink (some pirouetting, some circling), makes you think about your relationship to the artworks on show (in the museum you witness and applaud the pirouetting and perform the circling).

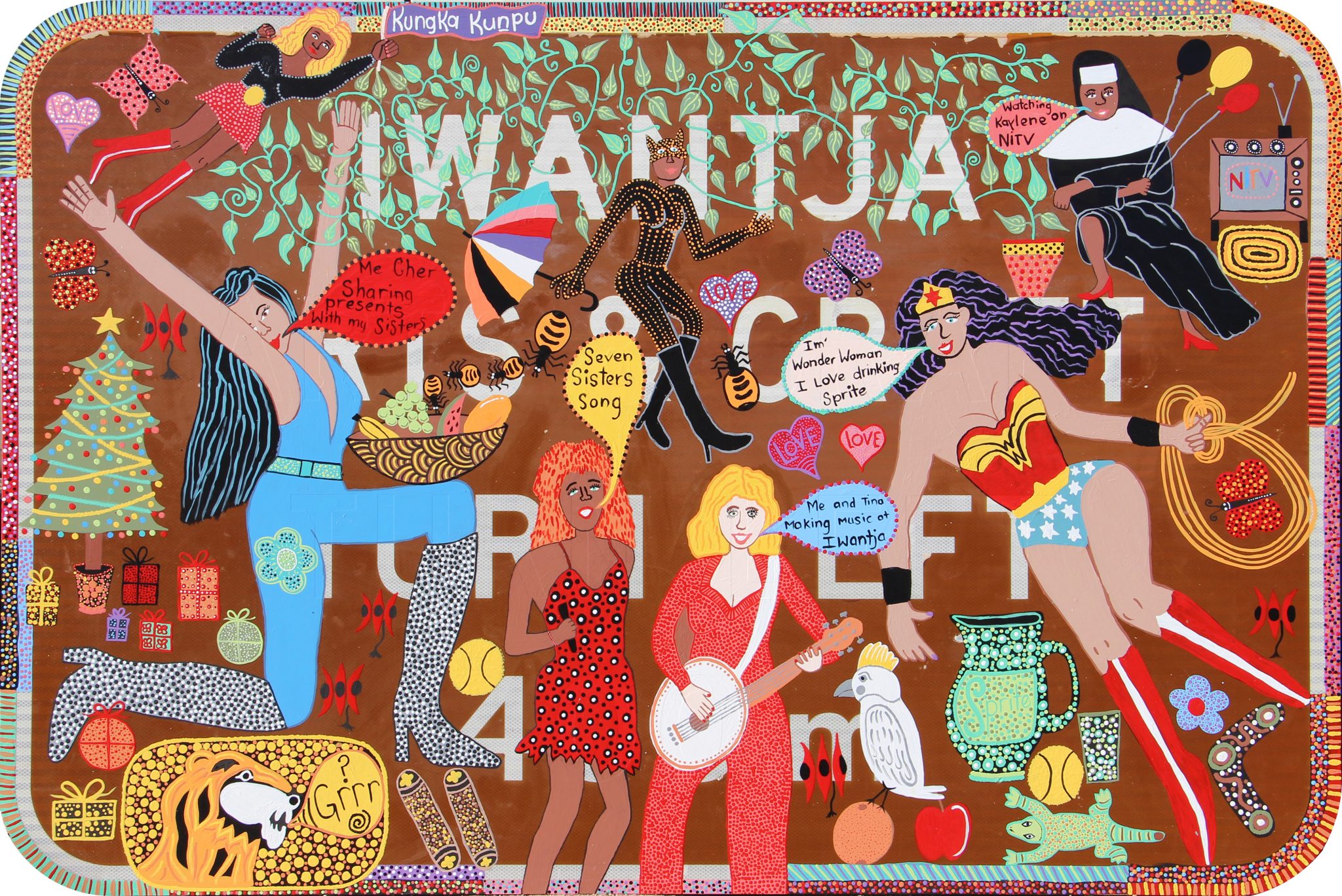

Similarly effective are videoworks dealing with migration by Tuan Andrew Nguyen (particularly The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019, which deals with issues of identity in the entanglement of Vietnam, France and Senegal and is shown in a shipping agent’s house in Tokoname) and Ngura Pukulpa–Happy Place (2022; a videowork shown in a former nursing school in Ichinomaya) by Kaylene Whiskey, in which the Australian Aboriginal Yankunytjatjara artist fuses Aboriginal and aspects from globalised Western culture in a desert party that both celebrates and defies aspects of the Aboriginal (and indeed, more generally, indigenous) as we imagine it to be (while also highlighting the absence of any reference in the exhibition to the plight of the Ainu people in Japan). In short it’s the messy bits of the triennale that work best. Nowhere more so than in Bunsho Hattori and Ryuichi Ishikawa’s The Journey with a Gun, and No Money (2022) – an account of a one-month trip to the north of Japan with the items listed in the title. In a former pipe factory in Tokoname it’s presented as an installation of their survival equipment, the skins of deer that they hunted for food, recordings of the sounds of the journey, photographs and texts and a modestly priced booklet. The living and the dead working together. And, like Kawara used to do, it performs what it says on the label.

Aichi Triennale 2022: Still Alive, across various venues, Aichi Prefecture, through 10 October