An exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo refutes the Western assumption that AIDS is an isolated epidemic from the past through new conversations between artists dead and alive

Translating a book into an exhibition is no easy task, particularly a book as rich and nuanced as Elisabeth Lebovici’s art history-memoir hybrid Ce que le sida m’a fait (What AIDS Did To Me, 2017). All in all, the curator François Piron did a decent job: much like the book that inspired it, Exposé·es at the Palais de Tokyo is less interested in art about AIDS than in what AIDS does to art. And while the show features many of the usual suspects – David Wojnarowicz, Derek Jarman and Nan Goldin, to name but a few – they are innovatively contextualised through rarely seen works and unexpected conversations.

From the gallery’s entrance, a yellow banner with red capitalised lettering by American artist Gregg Bordowitz sets the tone: ‘La crise du sida ne fait que commencer’, it reads (the English translation – ‘The AIDS crisis is still beginning’ – appears at the back). As a queer Jew and keen reader of critical theory, Bordowitz challenges the notion of linear progress in favour of what Walter Benjamin calls ‘Messianic time’ – a radical engagement with history through the present. This message announces the exhibition’s intention to trouble the Western assumption that AIDS is an isolated epidemic in the past.

Drawing on this notion, the exhibition orchestrates a number of thoughtful conversations between artists – dead and alive – across generations, media and territories. In homage to Felix Gonzalez-Torres, British artist Jesse Darling has filled two large glass boxes with the late Cuban-American artists’ leftover works, including bead curtains, broken lightbulbs and hundreds of cellophane candy wrappers.

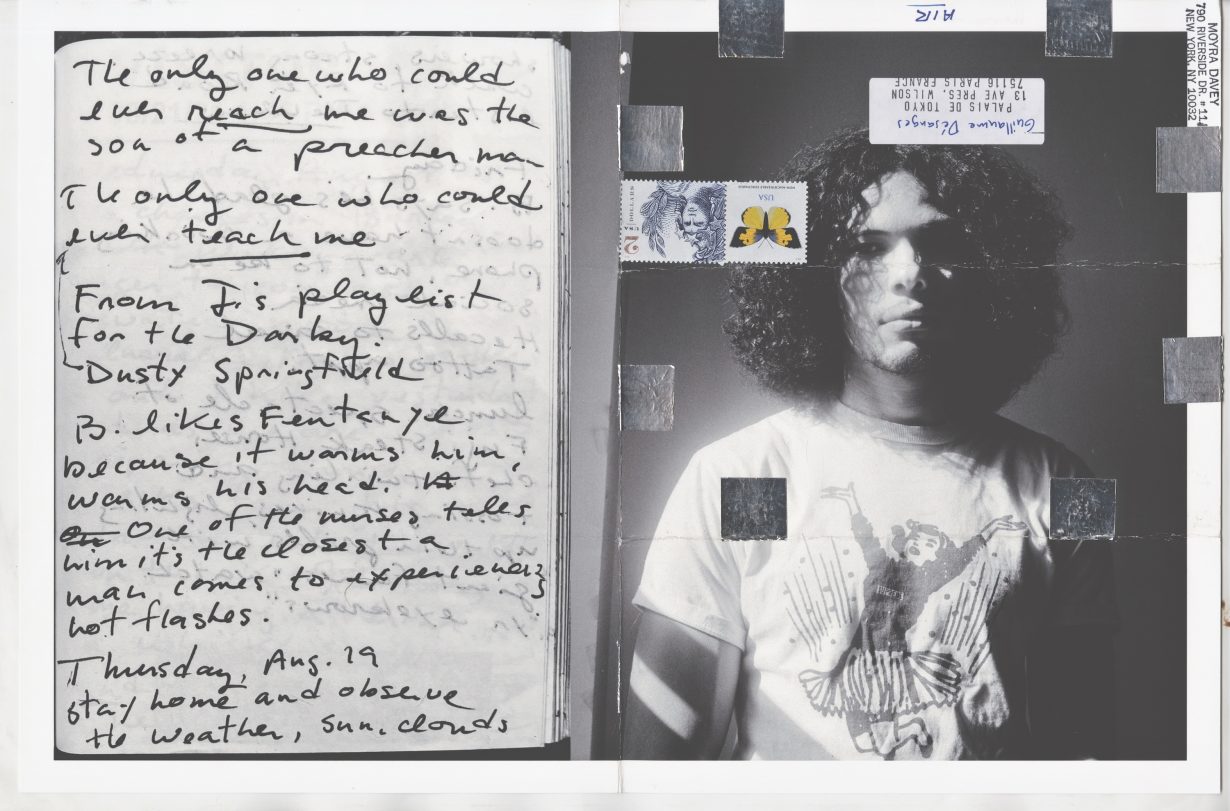

In another room, Canadian artist and writer Moyra Davey shows a series of recent black-and-white photographs alongside copies of a diary she kept while visiting her son in hospital while he recovered from an accident. Titled Visitor (2022), the works are inspired by the photographs of the late French artist and novelist Hervé Guibert – remembered for his playful and candid accounts of living with the virus during the late 1980s – some of which, including self-portraits, are shown on the opposite wall. In Davey’s photographs, her son – who must be about the age Guibert was when he took his photographs – is seen mimicking some of the latter’s poses, choreographing an intricate dialogue across time.

Video too is front and centre. Rightfully so, given that the emergence of AIDS coincided with the availability of the camcorder and editing technology that became central to counter-representation strategies. Illustrative of this turn is Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS (1986), a short video by the late lesbian feminist filmmaker Barbara Hammer, whose postmodernist aesthetics influenced video activists such as DIVA TV and Bordowitz. Made at the height of misinformation about the epidemic, the film juxtaposes newspaper headlines such as ‘Mosquitoes Can Spread AIDS’ with shots of Brent Nicholson Earle’s highly mediatised 16,000km run to promote sexual education. In the same room, a series of short experimental films by the late magistrate-turned-writer Guillaume Dustan – an advocate of bareback sex in early 2000s France – play in a loop on a television set. While they’re not particularly interesting in and of themselves – mostly consisting of shaky, uninterrupted shots of Dustan’s everyday life – these strange videos show a little-known aspect of the writer’s practice. In another room, a deeply moving yet entertaining autobiographical film by Lionel Soukaz – a member of the 1970s Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire – documents the end of his partner’s life. Titled RV, mon ami (1994), it forms part of the filmmaker’s expansive archival project Journal Annales (1991–2001) that he recently donated to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The downside of having so many videos, unfortunately, is that they make a lot of noise. And while the notion of ‘sonic infection’ certainly suits the theme of the show, all that cacophony leaves little room for quiet introspection.

Exposé·es is an ambitious exhibition which, in the wake of a new and ever-evolving global pandemic, shows that a virus transcends history. However, the beauty of the book it claims to celebrate lies in Lebovici’s unapologetically personal voice. It is a shame that this subjective approach was abandoned in favour of a more institutional outlook.

Exposé-es, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 17 February – 15 May