Across largescale tapestries and adroit conceptual works, The Dream Pool Intervals at Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery examines the destructive forces in the world

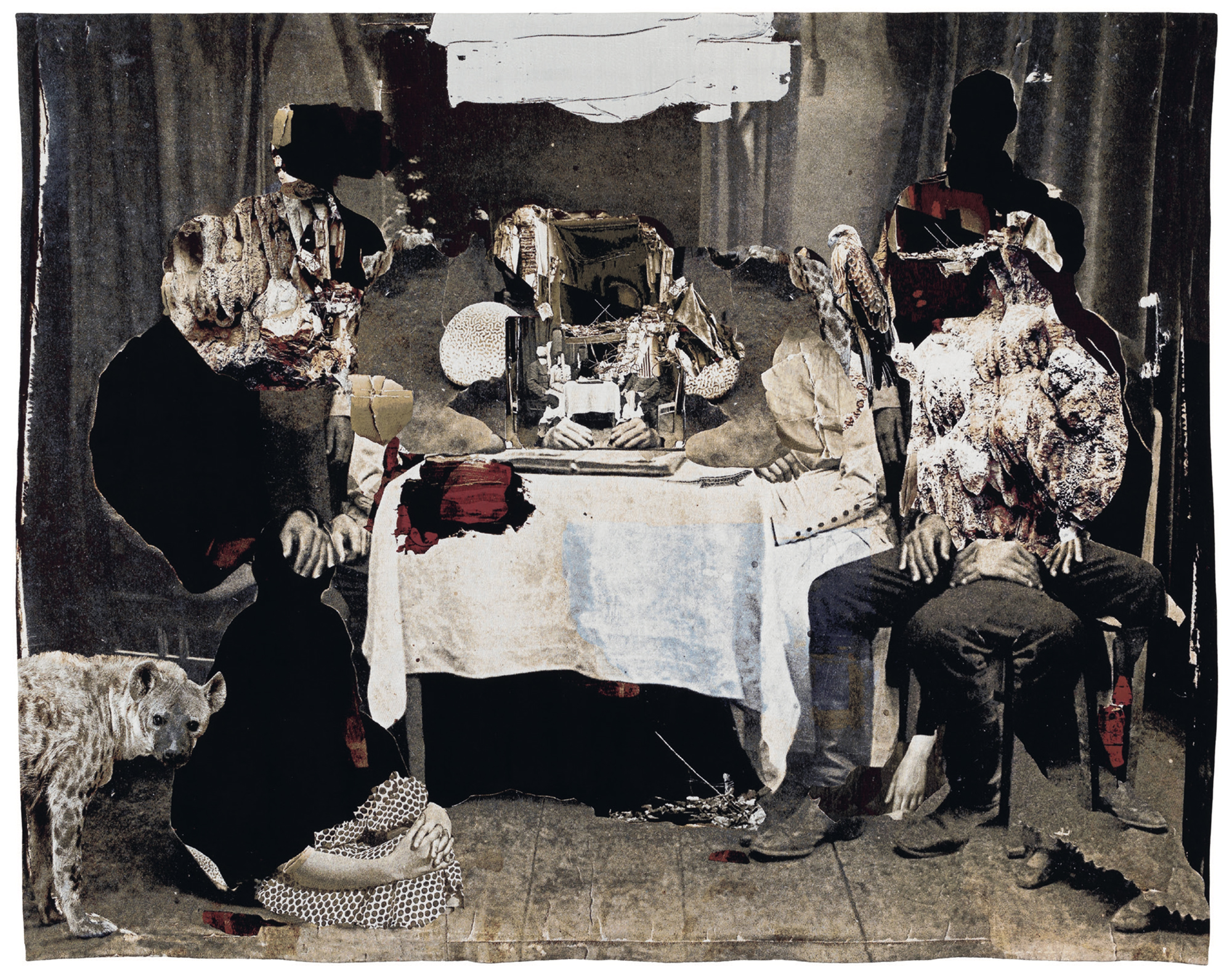

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain’s The Dream Pool Intervals foregrounds one fundamental opposition: time – omnipotent, inevitable – and our attempts to resist it and assert ourselves on it. Across five largescale, digitally produced tapestries, these Intervals (all works but three 2025) are photomontages splicing together documentation of deep-cave expeditions, historical photographs of wealthy, Industrial Revolution-era families and images of architectural destruction. The centre of Interval III (2024), for example, is taken up by a desaturated photograph of a family at the dinner table. Some faces are blacked out into hollow ovals, while others are overlain with rough, chalky patches – what from afar seem like rock formations become, up close, more like plumage, wool and silk weave catching the gallery light. The torso of a figure at the head of the table is substituted for what appears to be a miniature of the same photograph. In the lower corner, meanwhile, a hyena looks towards the viewer, hungrily.

In fact, similar descriptions befit the entire series: a frame within a frame, blacked-out faces, discordant injections from the natural world, and abstract red smears like dried blood to lift the works out of their sepia-toned anachronism. Within each tapestry, Ní Bhriain stages a confrontation between anthropological history and deep, geological time: in Interval II, the centre of the photograph on the tapestry seems to peel away from within, revealing the brilliant distortions of a ray of light, and an icy blue stalagmite, standing magnificent – as if to say, this will last. Her medium, too, garners a certain material awe: each work towers over the viewer, almost overwhelmingly full; their aura of power comes from the medieval French and Flemish traditions of tapestry weaving, produced at great cost for royalty and regency to peacock and narrate their might. Here, though, there’s scant narrative to be found. Not retelling the stories she has pulled out and vandalised evidence of, nor critiquing them, Ní Bhriain’s works omit the actual human events, lives and faces of the people whose gaze we try to meet – and, in doing so, anaesthetises them. Instead, her tapestries gather all the effects into one, like rubble – spectacular, melancholic, inscrutable.

The second half of the exhibition constitutes a series of more conceptual works, dramatising the push and pull of time and preservation – a posthuman privileging of decay, dissolution and obliteration. The centre of the gallery is occupied by empty, low glass vitrines, atop of which Ní Bhriain has placed antique ceramic pots, undecorated and bathetic. Nearby in Untitled (surface #6), a pocketsize framed photograph has been brushed over in a greasy marmite-brown slick of bitumen paint. The image is protected from damage, and simultaneously its essence (as a photograph, its ‘moment’) is destroyed. On two perpendicular walls, Picture XII, Diptych and Picture IX present a process of germination. On one side of the former, a broad white pigment print seems speckled with black – like an expressive flick of paint, or fungal mould. On the latter, a similar white print now has a huge hairy black patch through the centre. So it’s confirmed: mere spores have become a growth, a domination of nature over the manmade document; blink and you’ll miss it.

If there’s anything to effectively draw these works together, it’s this pervasive sense of exposure: relics removed from their protective casing, vulnerable; animals circling as if attuned to a scent; artworks overrun by the elements; the past dragged out into the light. Ní Bhriain’s creative redux seems to be suggesting: these things are rotting, and perhaps we should let them.

The Dream Pool Intervals at Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, through 28 September

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.