Festim da alma at Mendes Wood DM, Paris interrogates the marginalisation of Black culture in Brazil

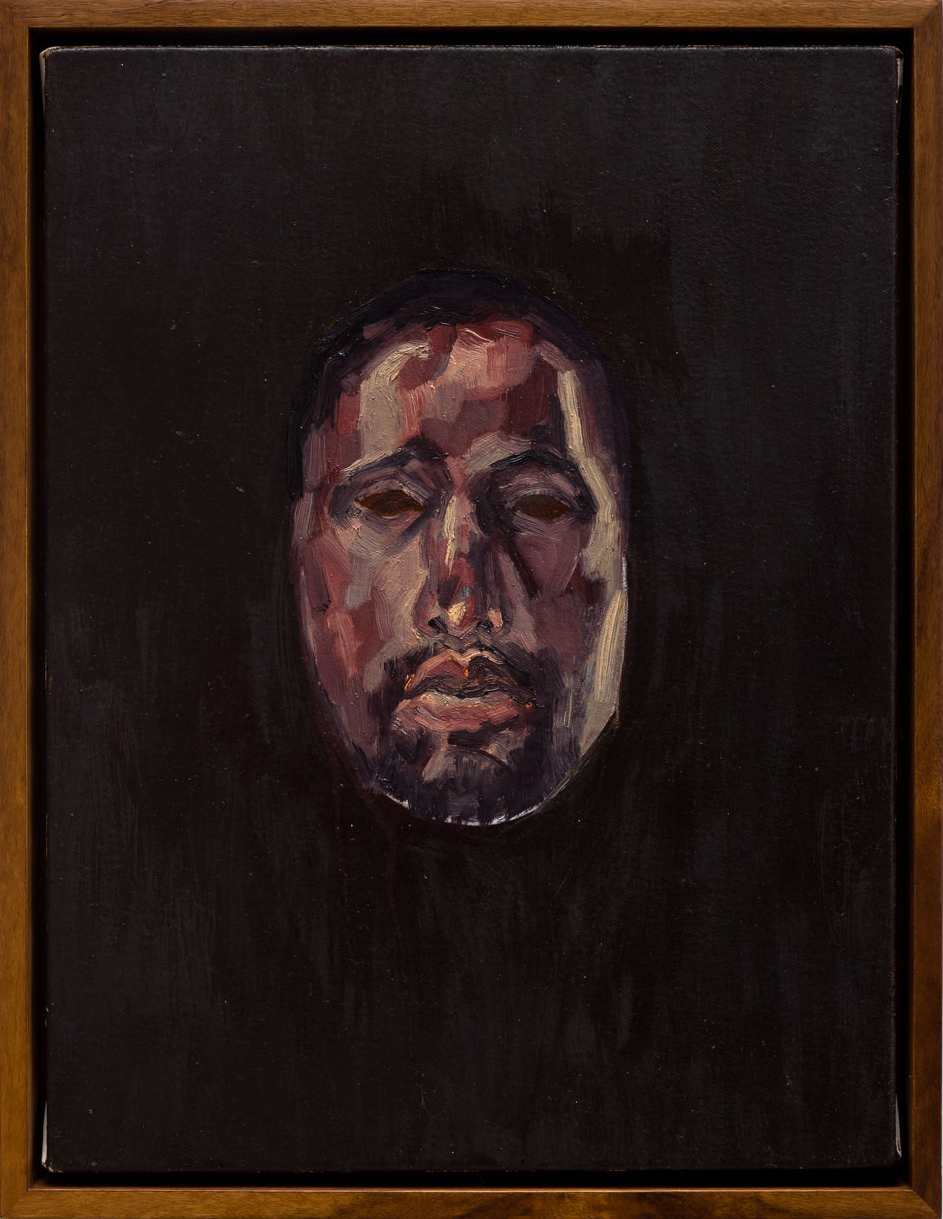

Antonio Obá has an axe to grind, and quite understandably so. His chief concern is the marginalisation of Black culture in his native Brazil – and the fact that the country has all but buried its considerable debt to Africa in the creation of a national identity. His work is heavy on symbolism, mysticism and allusions to cultural syntheses between Catholicism and Candomblé spiritual traditions. This exhibition of recent paintings and drawings follows much the same formula, while also – as its title, ‘Feast of the Soul’ in English, hints – proposing to chart the progression of a life cycle. The first image we see, Alegoria para uma nascida (Allegory for a Newborn, all works 2024) is a trompe-l’oeil conundrum in which Obá displays a virtuosic defiance of pictorial confines: a young girl gazes out defiantly from an arched false frame, her foot stamping on a sinister white snake; the last, Autorretrato enquanto máscara (Self-portrait as a Mask), features what looks a lot like a death mask based on the artist’s own likeness.

Unignorable suggestions of the historical and cultural processes that characterise so much of Obá’s work come with Contenda – 2: A Dança (Contention – 2: The Dance). The painting’s composition sees two men – both Black, both clad in identical, quasi-ceremonial white pyjamas – locked in a dancefloor embrace, surrounded by manicured, soft-focus vegetation. Two sets of decorative railings, capped with distinctive spearlike tips, form a partial enclosure around the figures, the former rendered in an irradiated red at odds with the otherwise gentle palette and brushwork: they make sense within the representational logic of the composition, but are somehow not quite of it. This semiabstract physical barrier could be read as a representation of constraint, even its ornamental flourishes projecting a sense of menace.

And yet: the tranquil scene playing out within its confines hints it might be less a carceral structure than a means to keep the rest of the world out. ‘Contenda’, as referenced in the work’s title, is a particularly complicated subdiscipline of the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira, a practice commonly understood as a form of resistance to slavery and a neat metaphor for Obá’s own relationship to painting. Paris gallerygoers may read the scenario as an illicit homosexual tryst; otherwise, an ‘othering’ of Black custom. Yet what if it really is just a straightforward depiction of a tradition few outside Obá’s own self-identified community can be expected to understand?

Obá, whose adopted surname means ‘king’ in Yoruba, thrives on such contextual ambiguities. For Criança de coral (Choir Child), 14 bloodred plinths arranged in a wide curve support portraits of children participating in a Catholic choir, apparently based on photographs. When they’re viewed individually, any unity of purpose is lost, and to the uninformed eye they look as though they’re yelling in anger or, more likely, agony – the illusion of organised joy, as any lapsed Christian will attest, is hard-won. For all the formal novelty of the display, however, it lacks the nuance we see in Contenda.

Similarly, though rather more subtly, the moths that invade the dancefloor depicted in Memento Mori – Baile de debutantes (Memento Mori: Debutante Ball) (a scene referencing the first debutante ball open to Black Brazilians, in Belo Horizonte in 1963) may not represent the pestilence we might assume. These insects, one indigenous species of which feeds on the tears of animals, are a recurring motif in Obá’s paintings: the gallery literature describes these creatures as observers to the scene, but might they actually be lapping up the weight of historical prejudice? You’re left wondering: might a reading based on historical, culturally specific symbolism be simplistic in this instance? Obá leaves us hanging, as well he might.

Festim da alma at Mendes Wood DM, Paris, through 27 March

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.