Jean Baudrillard was born in Reims in 1929. A sociologist and anthropologist influenced by pataphysics and the Situationists, his first book, The System of Objects, came out in 1968. Later publications announced pessimistic concepts of the end of art, end of reality and end of origins, and contemporary culture as an endless procession of simulacra. He became a cult figure for the artworld during the 1980s, but by 1996 he had published a notorious essay, ‘The Conspiracy of Art’ (published in English in 2005), in which he denounced contemporary art’s irredeemable nullity. He died in Paris in 2007.

ArtReview

What do you think about art being flipped at auction?

Jean Baudrillard

Why should I think anything about it?

AR Because you’re a thinker and you’ve written about art.

JB I never wrote about it from the point of view of enthusiasm. So if something cynical is going on with it, it’s no surprise to me.

AR Do you secretly like any art?

JB When I was alive I made no secret about admiring Warhol. But it’s not ‘liking’ like saying, ‘Hurray!’ I believed he showed the nothingness of art in a ruthless fashion. The first time I saw a lot of Warhols as opposed to reproductions was at the Venice Biennale, in 1990. I met you at the same event, Matthew. I have followed your interviews in ArtReview with the dead, in which you get great minds of the past to speak the things you think yourself.

AR Thank you. Once a religious guy on the TLS emailed to complain my TV programmes were nothing but a postmodern hall of mirrors. It made me think of you as the cliché figurehead of this pessimistic image in which there is only endless relativism. But in fact you are saying that absolutes ought to be delayed a bit, sometimes, not denied altogether. During the 1980s I read your books and was daunted by their extremely jaded and sardonic air. It never occurred to me that you didn’t really know anything about art. But later I realised your conclusions about it were right anyway. By then no one cared what you used to think. Your old enemies in the world of intellectual thought, English philosophical positivists, hardened old Marxists, are not necessarily riding high now. But when they say you are nothing but a mystifying joker, no one shouts them down.

JB I create my own systems, and they are not there to be admired but to be engaged with as arguments.

AR No one thinks about Warhol either. It’s taken for granted that he’s great because of the market prices. It’s no longer the age where there are important seminars discussing him.

JB Well, c’est la vie.

AR Have you seen any good shows?

JB Yes, I liked Inventing Impressionism at the National Gallery, London.

AR God yes, it was fantastic. I mean, not the theme, Paul Durand-Ruel, the art dealer, ‘inventing’ Impressionism…

JB No, not that. That’s just cultural business as usual. The elevation of commercialism to the highest value, as if Monet putting colours side by side is on a lower level than Durand-Ruel at the top of the value system putting consortiums of buyers together, and evolving new strategies of art display and art publicity.

AR The interviews with you that followed the publication of ‘The Conspiracy of Art’ are funny examples of cross-purpose conversation. The interviewers want to sound as if they are part of something they imagine is important: the artworld. They’re shocked that you could be indifferent to it. In the meantime, in your answers to their questions you clearly also don’t have any knowledge of what you’re attacking, and yet what you say sounds powerfully feasible. You say the whole world becomes a readymade. Art becomes anything and anything becomes art. Everything becomes Disneyland. The whole world gets transformed into aesthetics and aesthetics gets transformed into the whole world, and aesthetics can’t be meaningful when that happens. The only thing I think you put rather misleadingly is your notion that art is traditionally expected to reveal ‘reality’ or ‘truth’. I mean, that might be part of the rhetoric of art appreciation, but truth and reality are not what art reveals so much as it does another kind of reality than the one that, without encountering art, we would normally inhabit. The disrupting of habitual ways of seeing that art accomplishes – its surprise effect – alerts us to possibilities of life experience beyond what we would otherwise accept as the only life there is. In that sense an aesthetic kind of art is potentially revolutionary.

JB That’s well put. I suppose it’s why I liked the Impressionist show so much. It was incredibly visually rich, even though it was repulsively lit with angry spotlights in a nasty dark subterranean basement.

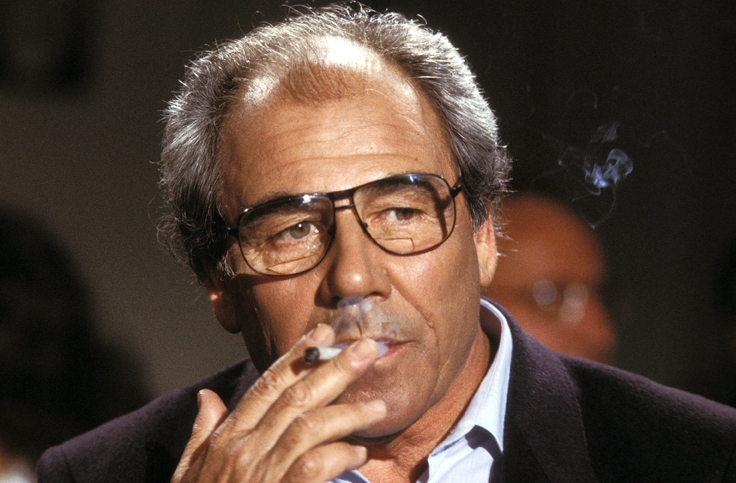

Jean Baudrillard, Saint Clement, 1987. Courtesy Marine Baudrillard

AR Yes. Impressionism is the moment when independence becomes the big theme in art. Art becomes its own drive. It offers aristocratic meanings of sensitivity and heightened seeing, but the artists themselves actually range in social status from aristocrat to worker; the audience is bourgeois; and the mood of the whole interaction between a free art and an audience prone at first to hostility and then to scandalised curiosity is democratic. You don’t need to be highly educated. You only need to have cultivated your responses to art. You need to have had the time in which to do that and the sensibility to wish to do it. Not everyone can or wants to. Most people in the artworld as it is today certainly don’t have the sensibility that can appreciate the jostling microcosms of buzzing energy that make up an Impressionist painting, whether it’s Renoir or Monet, Pissarro or Cézanne. But in any case, at that time, when the movement began, this rich independent artistic meaning was all conveyed via the reduction of everything in life to light: so there’s the question of whether the Impressionist ‘turn’ is an isolating move or a compressing one. Is ‘everything’ (the world; reality) somehow there but transformed into an image that ostensibly conveys only fleeting light effects? Or have most things been left out in order to concentrate on the charm of light effects alone – in order only to be charming?

JB Impressionism certainly is charming.

AR The mental framework doesn’t exist in art presently where charm can be put together with critical power and genuine sensual impact, as they go together in Impressionism. Anyway, anything else you’ve seen?

JB Yes, I saw a show by the Israeli artist Yael Bartana. It consisted of two films. One was immediately idiotic and I wanted to leave. But when I saw the other one it was immediately very funny, and I was forced to question my responses to the first one. I realised that was funny too, but the humour was so subtle and clever I hadn’t been able to gauge it. This brilliant artist genuinely challenged me. However, I looked her up and it turned out both films are as solemnly pretentious as each other and her motivations are dull as ditchwater. If you make the mistake of going, only watch the second one and see it as a comedy. It’s called True Finn. Actors impersonate different ethnic types who all think of themselves as equally Finnish. A sociological experiment brings them together in a commune for a short time, where they have regular earnest discussions about national identity. Passive-aggressive narcissism reigns in every scene. Every now and then a few frames from stiff, old-fashioned Finnish films about folksy authenticity are cut into the film, to add to the hilarity.

AR But you said it wasn’t funny in reality?

JB Don’t bother with the reality. The protagonists are not actors at all. Instead, they really are different ethnic types whose unbearable emotional fakery in the film, which had seemed very funny, is in fact their true fakery.

AR What’s the first film?

JB Actors pretend to have emotions in relation to typical Hollywood disaster movie special-effects. The context is something to do with the full-size replica of the Temple of Solomon recently built in São Paulo. The film has no redeeming features. Naturally art critics are breaking down in tears being deeply moved by it.

AR In ‘The Conspiracy of Art’ you denounce art’s complicity with the powers that be.

JB It was nothing new for me. My book For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1972) includes the statement that contemporary art is fatally ambiguous, part terrorist critique and part de facto cultural integration. And in The Consumer Society (1970) I said there wasn’t anything subversive about Pop art, ‘its cool smile no different from commercial complicity’. I always say contemporary art is nothing but ‘the art of collusion’. It’s much more blatant even today, long after my death, when art either frankly colludes or else frankly denies its own reality.

AR You only look at the art power scene.

JB There exist many attitudes towards art – takes on it that don’t conform to the artworld attitudes I attack, and that attack them for the same reasons I attack them.

AR But they’re not having much effect?

Art that wishes to be seen as something else, more hopeful and beautiful, is an art of complicity all the same, because it simultaneously strives to be applauded by the system it flatters itself it’s turning its back on

JB Exactly. The artworld that dominates does so because it entirely reflects movements in society to which we are all now subject. Art only reflects them and is complicit with them. Art that wishes to be seen as something else, more hopeful and beautiful, is an art of complicity all the same, because it simultaneously strives to be applauded by the system it flatters itself it’s turning its back on. The problem, as with culture and society generally at this stage, is that there isn’t any other system. The whole point about the ‘hyperreal’ and the ‘succession of simulacra’ and the end of any possibility of the ‘real’ – these terms from my books – is that there is no real art somewhere behind this spectacle of inanity that contemporary art presents. Nostalgic reactionaries pretend to seek this real object. They pretend to seek truth.

AR I can’t think of any photos by you that I’ve seen, but I know I must have seen some. They are of things like swimming pools, or deserts, or rearview mirrors, I think. Do you like your own photos? Do you say they’re just as inane as anything else? You agreed to exhibit them in an art context.

JB Yes, I liked taking them. I agree it’s a bit up-in-the-air for me as to what I thought I was doing when I exhibited them. At the moment I took them I was capturing a certain light, a colour disconnected from the rest of the world. I felt it was even disconnected from myself. I was capturing my own absence, making other things appear. I never thought aesthetics were involved. I never cared if anyone judged those photos to be beautiful or not. I must say I like your collaborative paintings with Emma Biggs for the same reason. It’s clear that aesthetic issues are not possible at the moment in the sense of them being at all effective in relation to a wide audience. So in effect they are unreal. They are fetishistic only. But I appreciate that in your paintings there is an impersonal logic of different visual orders that have equal authority even though they cannot be seen at the same time. In other words they displace each other without any of them seeming more or less important. Of course it’s of no use to anything going on at the forefront of the art scene now. And its use or point in the world generally is dubious at best. It was my friend Paul Virilio who said aesthetics only develop if there’s a more or less common view of the world.

AR Yes, he said it in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, shortly after that time we met in Venice. ‘At present this is, however, not the case,’ Virilio says. He continues: ‘Our seeing is done separately, individually. An aesthetic of seeing does not exist in reality. Here we are faced with a basic change, a mutation of life.’

JB Good point. I read a good interview with you once, Matthew, in which you seemed to want to elevate only embarrassment as far as the art scene is concerned, and you seemed to be opposed to any kind of enthusiasm.

AR Yes, I know the one you mean. It’s funny; the interviewer sent me an email with questions supplied by the editor, but he didn’t seem to notice – or thought I wouldn’t mind; or it didn’t matter if I did – that this editor had written in a covering letter that it was well known I would write anything for money and I should be challenged about that. Here I was, making announcements perceived by the art powers-that-be to be career-suicidal, like saying Greenberg and formalism aren’t so bad; and overlooked British abstract artists are just as worthy of attention as spotlit, overindulged ones like Jeremy Deller; and the commodity critique needn’t be the be-all and end-all of how art is understood. And at the same time I’m being accused by the same powers-that-be of thinking only about my career. In makes me think of you and your indifference to scorn from what was, at the time, thought to be your most important professional sphere. Just now you mentioned the concepts in your books with which the artworld in New York during the 1980s became infatuated. After ten years of being praised, you turned round and said contemporary art passively and collusively repeats what goes on in Western society anyway, it doesn’t criticise it or see it in some specially transcendent prophetic way. Once that message of yours was received, you were quickly forgotten as a guru.

JB I was forgotten in the days of Sherrie Levine and now I’m still forgotten in the days of Chinese contemporary art endlessly depicting Mao ironically, as if by doing this they believe something important could be happening. And the time of sleazy art advisers on Facebook dictating the shallow and ignorant levels at which art is discussed.

AR Wouldn’t you have liked it if the artworld responded to your message in 1996 by actually setting about changing its act? And you were appreciated as the cause of a new genuine optimism of art?

JB That’s a hypothesis that could never be a reality. My point of view is anthropological. From this point of view, art no longer seems to have a vital function; it is afflicted by the same fate that extinguishes value, by the same loss of transcendence. I’m a critical writer. I don’t have any interest in art, why should it have any in me? It was a mistake when that interest started up, and within a short time the mistake was realised.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.