I am a French intellectual living in Paris in 2016 under a state of emergency. I have a column in Charlie Hebdo. When I come by the magazine’s offices, I pass through multiple control gates, security checks and exchanges of small talk with the guards, into an atmosphere that is warm and studious; spatially, however, I feel like I’ve just entered a parallel universe. Even in this article, I am not able to provide details of the space and its security system. It’s something straight out of a novel, but at the same time dizzying. I’m confronted by a paradox: it’s better not to talk about that which protects my freedom of speech.

I would never have thought that one day an armed guard would be watching over me while I write. I can’t get used to it.

This paradoxical security generates an aesthetic – ‘the bunker’, as it’s known, is beautiful, white, bright and as isolated as a space capsule. At dusk the guards close the blinds, as the opaque and – of course – armoured windows let the electric light through. The guards act stealthily, like cats: we go to work in civilian clothes; they work in bullet-proof vests. I would never have thought that one day an armed guard would be watching over me while I write. I can’t get used to it.

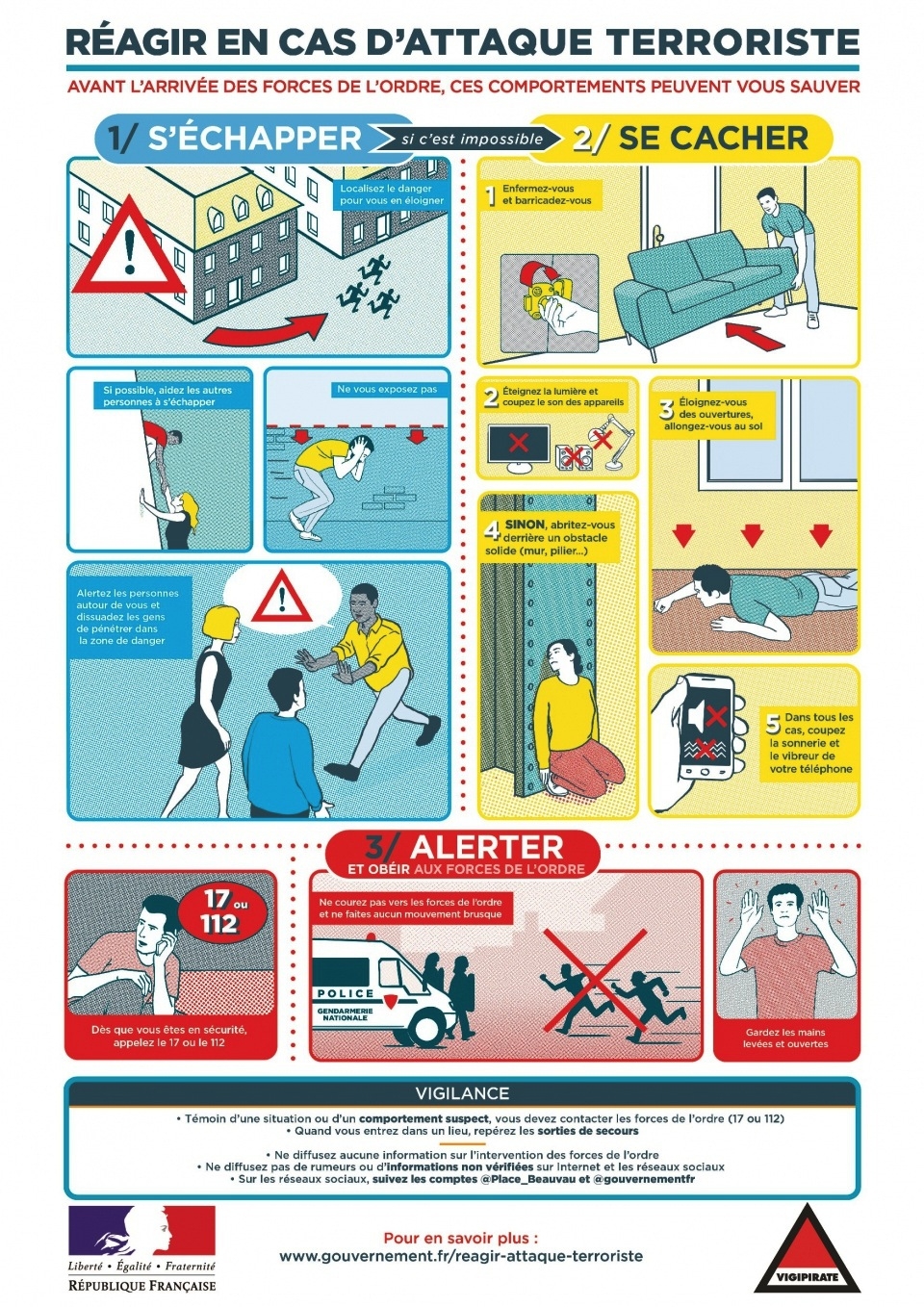

Meanwhile, I’m also an adviser on the Paula Modersohn-Becker exhibition that will take place at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (MAM) from April to August. The first thing one sees upon entering MAM’s offices is a ‘how to react in case of a terrorist attack’ poster, which is present in all public spaces in France. With a strangely dated look, like some 1970s Air France flyer on plane-crash measures, it recommends that you 1) escape 2) hide 3) raise the alarm. What does the museum have planned in case of an attack? “The subject of security being a very sensitive one since the attacks, we do not wish to communicate on that matter,” the communications department tells me. The subject can’t be addressed. The communications department won’t communicate. As for me, I think I’d rather not talk about it either – out of superstition. Escape. Hide. Don’t talk about it. I don’t know how many more attacks it will take before Parisians feel besieged. For now, no one I know is considering leaving. But if people were prevented from going out – galleries, theatres, ballets, cinemas, etc – morale would collapse. It’s the possibility of going out that defines the city’s inner freedom.

Wolfgang Werner is one of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s biggest gallerists. This elegant, rational and Buddenbrook-like man was born in Bremen – also the artist’s hometown – in 1944. He used to play, as a kid, among the ruins. He shows me, casually, black-and white photographs of the artist’s missing works, which disappeared during the air raids. This man tells me he doesn’t know whether the show will take place – I worry: is there a problem with the loans of the paintings? No, he says, it’s just that “anything could happen”.

Over the past three years, I have been going to Bremen quite often. In Paris we don’t notice the refugees, because physical types and their clothing are varied and cosmopolitan: undocumented migrants mix with ‘documented’ citizens, no visible signs of legalityin either group, state of emergency or no. But in Bremen… Blond families with children. Hardly any tourists. And young men, in groups of two or three, walking around wrapped up in their coats. They are mostly Syrian. The city had been managing to accommodate them, but with the recent influx, they are now being sheltered within gas-heated beer tents. By the cathedral, on the Marktplatz, some 50 demonstrators hold a sign that reads: ‘Frau Merkel, unsere Toleranz hat Grenzen.’ Mrs Merkel, our tolerance has borders. It’s 24 January, three weeks after the New Year’s Eve assaults on women in Cologne, Hamburg and other city centres across Germany. I don’t know what will become of that tension, that imbalance. I know some of the Paris attackers were born in France. I know it’s the possibility of coming and going that defines the inner freedom of our planet. I know it’s the possibility of welcoming the other that defines the inner freedom of each earthling. We are living in tragic times.

This article first appeared in the April 2016 issue of ArtReview.