Somewhere in the narrow-laned former gangland district of Psirri – its seediness long since raked over into a vibrant, still-scruffy entertainment district – a piece of graffiti proclaims Athens to be the new Berlin. It is a leering aside at the hope-turned-cliché heralding the city’s recovery that has reverberated through the Greek capital’s depressed downtown for years. The upturn is just around the corner, politicians tell the media who pass on the message to the hopeful masses. Any moment now, it’ll be here, optimists inform each other, in a self-reinforcing patter reminiscent of bestselling author Petros Markaris’s latest detective novel, Offshore (2016), set in a financially buoyant post-crisis future characterised by a peculiar forgetfulness and the repetition of all the same mistakes. As Athenians continue waiting for Godot, hundreds of city-blocks in the centre of a European capital keep on subsiding into a prolonged decline whose causes far predate the crisis.

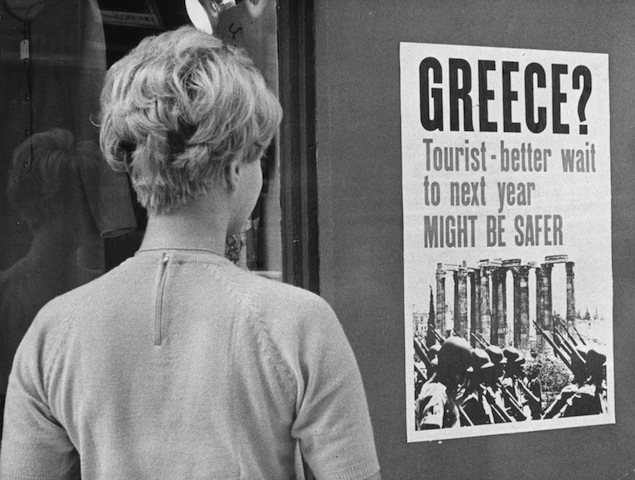

Athens’s mixture of a collapsed downtown and a cognitively unaware – or apathetic – populace is the context chosen by the German government-funded quinquennial Documenta for its 14th edition. Conceptualised ten years after the Second World War in reaction to Nazi bans on modern art and as an attempt to reengage with the world, the show is hosted by Kassel, a German town heavily bombed for being the manufacturing centre of Panzer and Tiger tanks. But as the war receded, Documenta took it upon itself to become a vehicle for the promotion of the avant-garde to repoliticise inert audiences and make culture relevant again; by the 1990s the quinquennial began to instrumentalise seminars, political interventions and critical analysis expanding beyond the exhibition format. Having already flirted with the Muslim world when Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev located part of the 2012 edition in Bamiyan, Kabul, Cairo and Alexandria (with mixed success) in addition to the usual base of Kassel, the artistic director of this year’s Documenta, Adam Szymczyk, decided to investigate Athens, a rundown Mediterranean port city located at an intersection of issues: the EU’s economic predicament, the refugee deluge and a series of other emergencies and crises of democracy in nearby Egypt, Libya, Syria and Turkey. Athens, for all its distractingly, defiantly vibrant bars and pavement cafes, is a no-brainer match – outstripping comparable cities such as Cairo, Damascus and Benghazi that lack the freedoms to organise such an event – as perhaps the greatest case-study of what it’s like to inhabit, at an advanced stage of its malaise, the capital of a zombie nation-state.

As Athenians continue waiting for Godot, hundreds of city-blocks in the centre of a European capital keep on subsiding into a prolonged decline whose causes far predate the crisis.

For three decades, the Greek equivalent of white flight saw middle-class Greeks flee the smoggy centre. They took advantage of the rolling cementification of much of the Attica Plain to provide a more spread-out, consumerist lifestyle to their families. Greece was post-dictatorship, a member of NATO, democratic (or at least regularly elective) and now a member of the EU too: its future glittered before its citizens’ eyes in the vitrines of garishly-lit hypermarkets and cement apartment blocks blooming out of traditional, low-rise neighbourhoods.

“The moment we knew we had to leave Kypseli was the day when our toddler came in from the veranda covered in soot from the car pollution,” one refined owner of a city-centre penthouse recalled as we stood on his terrace overlooking the Ministry of Development’s brutalist lines, an occasional drug addict staggering by below.

As that class of Athenian urbanites left (compulsively rubbing soot – real or imagined – off their offspring’s skin), foreign migrants from recently collapsed Albania and countries in Africa and the Middle East arrived to fill the ensuing vacuum. Their coming turned once-exclusive neighbourhoods wrought from luxury materials and dismissive worldviews into ‘Third World slums’, as they were referred to by the departing bourgeoisie, not without a trace of schadenfreude at ducking the deluge.

The new residents had worked hard to get to Greece but were neither wealthy, privileged, nor well-connected enough to make it beyond Greece’s borders. The hardscrabble ghettoes they created within Athens’s old centre rarely intercepted with mainstream Greek society, aside from informal, often exploitative employment arrangements or episodes of racial tension. The spaces vacated by those economic migrants who departed as Greece’s economy tanked were replaced by the more desperate refugees fleeing conflict in Iraq and Syria. As Northern Europe shifted from opening its borders to refugees in 2015 to paying peripheral countries to keep the newcomers at a safe distance, the cracks in Greece’s strained society widened: now the country was not just Europe’s problem child but its dumping ground too.

Much like famous, extrovert parents inhibit their children’s development, the city’s celebrated past distorts its present form: from the creation of the modern Greek nation-state in 1832 by an influential group of Western European officials schooled in romantic philhellenism (whose decisive intervention in the Greek War of Independence had something of Libya’s 2011 NATO-backed revolution about it); to the choosing of Athens – for purely symbolic reasons, and despite being radically reduced in size and importance from its late antique stature – as the new nation state’s capital during the nineteenth century; to the transplanting of Neoclassicism (an architectural style nurtured far from the Hellenistic world in Munich) and a Bavarian aristocracy to run the country. More recently, Greece’s acceptance into the EU on cultural rather than statistical grounds was another deviation from the more humdrum fate a country lacking a glorious past might expect. Just as distorting is the collective delusion imparted to Greek children that their genes derive – in an unbroken genetic line – from the imagined racial purity of the ancient Greeks.

Add to all this dysfunction narratives of ethnicities and minorities purged to make way for a state overwhelmingly composed of Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians, and you have fertile ground for an art exhibition that ought to challenge hegemonic, nationalistic narratives, upend ethnographic representations of Greece, and ridicule sundry other stereotypes about how we view our encompassing reality at a time of urgent global change.

At least that’s the intention behind this Documenta, which coincides this year with a Syriza government initially thought to be of the radical left, but which challenged that impression when it formed a coalition with the far right and performed a back flip in negotiations with its creditors. This resulted in the pro-Syriza media welcoming Documenta as effusively as you’d expect from a party with a rogue image to keep, while the opposition press responded with knee-jerk hostile coverage. Former Greek economy minister Yanis Varoufakis predicted that the event will devolve into ‘crisis tourism… like rich Americans taking a tour in a poor African country, doing a safari, going on a humanitarian tourism crusade’. And Iliana Fokianaki, an art critic and gallery owner, argued in Frieze that the focus of the advance public programme on ‘marginalised communities and activism in Greece and elsewhere’ resulted in a failure to address ‘the greater reality that glooms over Europe currently, one that affects all but the 1%: austerity, neoliberalism and capitalism’.

“Documenta will define Athens through involuntary selection, and in doing so subject it to an action where it’s not a willing participant”

“Athens is a fluid subject and did not ask or expect to be taught by anyone,” notes the Athenian artist Alexandros Mistriotis. “So Documenta will define Athens through this involuntary selection, and in doing so subject it to an action where it’s not a willing participant and which will obstruct the slow organic processes of the city’s informal development.” So, faced with discontent over a call out for members of the ‘chorus’ – essentially ‘local and international artists, students, activists’ and others acting as visitor guides – in which originally no fee was mentioned and ‘travel and accommodation costs… must be covered by the applicant’ (in later adverts Documenta clarified that the positions would be remunerated), together with other lurid rumours imparted to me by the more conspiratorial of the local art community, can the event avoid the charges of selling out? Can it attract – along the way – those ordinary Greeks who were never detached enough to view the crisis as an opportunity for introspection and whom actually never want to hear the word ‘crisis’ again?

They seem to be struggling. One Documenta event held in an experimental theatre space in the centre of Athens mid-March was attended by about 120 people, some of whom departed after the content was revealed to be a two-part lecture by Dutch and Greek curators Hendrik Folkerts and Eirini Papakonstantinou. The Dutch curator’s unattractive, jargon-heavy talk was offset by Papakonstantinou’s more engaging rundown of the history of Greek performance art. Conversely, the previous night, I attended a passionate two-hour debate on the identity of Athens at the Polytechnic, long a base of left-wing politics since the role it played in the overthrow of the Colonels’ dictatorship. Documenta was not mentioned once during the talk, and a group of attendants I spoke with after were upset at what they perceived as the organisation using Athens as a backdrop for a preformed agenda. (Amid heavy bandying of the word “neo-colonialism”, I asked Documenta for an interview but a spokeswoman replied that no one from the curatorial team had the time.)

With nearly half a million of the country’s youngest and brightest having left the country in search of fresh job markets, many of those who stayed behind dismiss Documenta’s events as Crisis 101 entry-level basic and unlikely to offer new insights. “Aestheticising the crisis and using Athens and Greece as vehicles for promoting an agenda are almost always presented as well-intentioned,” said Mistriotis, the artist. “Athenians carry a heavy history which makes them cautious in general; this is probably one of the first things they have to teach.”

One way in which Documenta’s events seek to avoid a stereotypical reading of the Greek crisis however is by examining how the country’s imperfect democracy (little more than three political dynasties batting authority across the net in a frantically spendthrift, three decade-long ping-pong contest) is the flawed result of the neoliberal processes that emerged from the 1967–74 military dictatorship. Roping in post-Marxist thinkers such as Antonio Negri, Judith Revel, Franco Berardi and Sandro Mezzadra for seminars open to the public introduces attendees to biopolitical, subjective and transnational readings of the reality afflicting Greece, and allows them to make connections to broader political themes that remarkably few Greeks (Varoufakis and a few leftist notable exceptions aside) have broached. But this is hard to pull off convincingly in what Greek critics of Documenta describe as a claustrophobic atmosphere of opaque application processes and a group of organisers perceived as failing to live up to their motto of learning from Athens. Three weeks before the event launches, the exhibition programme remains secret and artists and their entourages appear to inhabit an Athens largely disconnected from the city’s vibrant art and theatre circles. One Greek photographer recounted visiting the Documenta offices to follow up on her project application after not receiving a reply. She described being told by a staff member that artists cannot just turn up to solicit and must apply online. “Only projects of interest will be replied to,” she was informed, after confirming that she had applied online but not heard back.

How can a city, still shuddering from the delayed trauma of six years of deepening austerity, go about transcending the slightly unimaginative buzzwords coined by its public intellectuals?

Immersion is also a challenge Documenta faces. How does it plunge its non-Greek-speaking foreign artists into a local reality sufficiently inspirational to unlock compelling visual interpretations and tools that Greek and foreign audiences alike can relate to? Athens’s dysfunctional downtown is certainly an appropriate playground for such an endeavour. Twenty years of carefree spending, followed by six years of economic collapse, pulped parts of it into a stew of decrepit, desiccated and suppurating blocks of concrete shaped by a heterodox collection of groups into neighbourhoods with an intensely communal identity. Daring art galleries, self-organising public spaces (reclaimed from semi-privatised public land and run as autonomous parks), vibrant cafes and empty buildings administered by anarchist collectives and occupied by refugees, thrive among these darkened 1970s cement behemoths, alongside deserted commercial arcades, winking brothel lights and shuffling herds of addicts. The graffiti-smeared district of Exarcheia, known for its alternative politics, squatted buildings and anarchist groupings, first became the banner of this movement and then a parody of itself as eager foreign visitors booked AirBnB apartments in order to vicariously taste living in a so-called ‘no-go zone’, sniff the smoke from burning barricades, and post selfies of their escapades to friends and family back home.

As with the humanitarians who close themselves up in cement-ringed militarised compounds and mediate reality through bulletproof vehicles and local translators, I do catch myself wondering whether the journalists and artists who descend upon Athens’s shabbier neighbourhoods with the genuine intention of learning from their destination aren’t perhaps too tightly sealed into their respective professional, linguistic and cultural narratives. Tall, blonde northern Europeans sporting a resolutely non-tourist sartorial aesthetic are now a fixture in the lanes of Exarcheia, often accompanied by local companions with liberal sensitivities. It’s all a little reminiscent of Tahrir Square during the Egyptian Revolution, when Egyptian graduates of the American University of Cairo with perfect English and impeccable human-rights sensitivities latched onto non-Arabic-speaking foreign journalists and presented a rousing version of their struggle that was seductive, one-sided and dominant enough to skew the Western media coverage to the point that a whole series of how-did-we-not-see-it- coming articles appeared once first the Islamists were elected at the polls, and then overthrown by the counter-revolution and coup.

Often, though, the most perceptive outsiders intuit a place better than its average local. Szymczyk, Documenta’s rembetiko-listening chief curator, has already innovated by rehabilitating Athenian landmarks of suppressed history as debate venues, such as the site of the 1967–74 junta’s torture chambers. The Polish curator’s subtle understanding of Greek history and psychology comes through when he speaks about the cultural splits in Greek society that most locals resist discussing with outsiders. He speaks eloquently about this introverted country’s obsession with ‘Greek topicality’, referencing important Greek architects, painters, composers and other culture-shapers like Dimitris Pikionis, Jani Christou and Giannis Tsarouhis that many Greeks would struggle to identify.

Szymczyk’s mission is to stage a cosmopolitan event in an introverted country that shunned diversity for a century, while answering puzzling questions such as how one city, still shuddering from the delayed trauma of six years of deepening austerity, can go about transcending the slightly unimaginative buzzwords coined by its public intellectuals and the intense squabbling that has displaced public debate. Asking what a recovery might look like at a time of global economic, environmental and psychological freefall is the kind of question that is too often obscured by the heat of identity politics and what fresh disaster next week will bring.

The Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid recently wrote that, ‘the future is too important to be left to professional politicians… too important to be left to technologists either. Other imaginations from other human perspectives must stake competing claims. Radical, politically engaged fiction is required.’ Perhaps Athens’s Documenta can become a brick in this alternative reimagining of our present. But only if its participants, Greeks and foreigners alike, let go of the firmly-held worldviews, comfort zones and certainties contained in their smart phone screens and café circles, and embrace the uncertainty of engagement.

First published in the April 2017 issue of ArtReview