Nottingham Contemporary, 4 February – 30 April 2017

Visitors to this major exhibition of black British art from the 1980s are welcomed by Lubaina Himid’s lifesize cut-and-paste portrait Toussaint L’Ouverture (1987). What at first seems a straight-forwardly heroic depiction of the Haitian revolutionary leader is, however, complicated by the collaged tabloid newsprint representing his Napoleonic breeches, cuffs and boots. At the painting’s bottom right, these crinkled headlines – documenting the ‘terrorism’, ‘racism’ and ‘abuse’ endemic to Thatcher’s Britain – are connected by arrows to a handwritten legend. ‘This news wouldn’t be news’, the caption states, ‘if you had heard of Toussaint L’Ouverture.’ Thirty years on, the implication is that today’s news – of far-right nationalism, institutionalised misogyny and state-sanctioned violence against nonwhite citizens – wouldn’t be news if you had paid greater heed to the art produced by artists such as Himid.

In the second of four galleries stocked with videos, sculptures, paintings and abundant archival material, Zarina Bhimji’s She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence (1987) is an eloquent indictment of institutionalised racism. Here an intimate series of poetic fragments and hand-tinted photographs is enclosed in four Perspex panels suspended over a field of ground turmeric and chilli. The series’ callous conclusion in a pair of latex gloves is jarring until you learn that, during the late 1970s, scores of Asian women were subjected to ‘virginity tests’ when seeking entry to the United Kingdom. (This ‘news’ didn’t reach a wider audience until a Guardian exposé in 2011, fully 24 years after Bhimji’s work.) The revelation makes it harder to dismiss the current attempts to greatly restrict travel to the United States as exceptional, suggesting that our contemporary crisis is more deeply embedded and closer to home than those who identify it with a single billionaire fantasist like to believe.

That point is upheld by this exhibition’s occasional failure as much as is it is by its many successes. Sutapa Biswas’s Pied Piper of Hamlyn Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is… (1987), which depicts a pinstriped capitalist travelling by rickshaw through a ghostly Indian city, is one of the few works to play back into stereotypes that entrench rather than extend thought. Some of the more polemical work on show risks, for all its emotive power, distracting from the structural causes of inequality by focusing on its most repellent symptoms (another lesson worth learning).

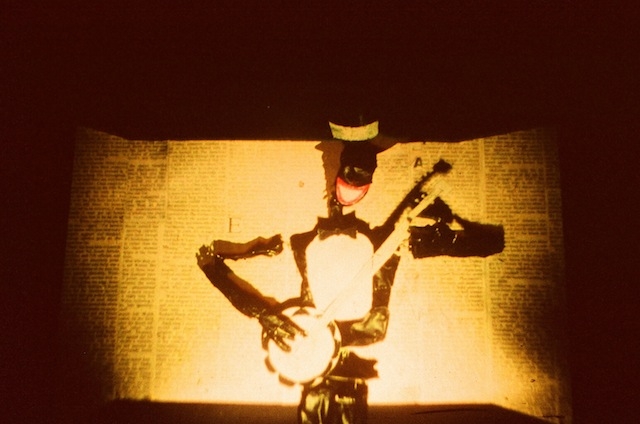

The show mixes work by Rasheed Araeen, Keith Piper and Himid (the subject of concurrent solo exhibitions at Spike Island, in Bristol, and Modern Art Oxford) with less familiar pieces by artists including Joy Gregory and Maybelle Peters. Peters’s Frantz Fanon-inspired animation Black Skin, White Masks (1991) is one of many examples of how hybrid forms such as collage, with their inherent ambiguities and resistance to material hierarchies, can serve to expose and undermine systemic injustices (not least in Black Audio Film Collective’s extraordinary Handsworth Songs, 1986). The highlights of this presentation are too many to mention, but one small caveat is that more explicit links might have been provided to organisations, artists and collectives engaged in the struggle today for the benefit of those inspired (perhaps the better word is radicalised) by the material. This is news, after all, that stays news.

First published in the April 2017 issue of ArtReview