It’s not all about Venice… ArtReview editors on exhibitions, film streamings and talks to catch this month

John Divola, Swimming Drunk at Yancey Richardson, New York

16 April – 21 May

In the photograph Zuma #52 (1977), windowpanes that almost entirely make up a wall of a room frame various views of a hazy light blue-grey seascape. The sea and sky are barely distinguishable from one another, save for the weak horizon line that separates the thin pattern of waves from the air above it. The view is serene. Inside the room, however, are signs of dereliction and abandonment: a pair of pale pink curtains, one hanging but ripped, the other lying half-crumpled, half-propped up by its attached curtain pole that leans inside the wooden frame of a dismantled windowseat; smashed window glass splashes across the floor; a piece of tarp hangs over the sill; several copies of newspapers lie in a corner, the pictures of which are unrecognisable, though each rectangular photo echoes the cool blueish tones of the sea outside. Two series made by the American photographer John Divola will be on display in his latest exhibition Swimming Drunk. Each take an abandoned building as a base from which the photos are made, but while Zuma (1977–8) marks Divola’s early photographic career, Daybreak (2015–2020) is one of his most recent series, pictured at the decommissioned George Air Force Base in Victorville, California. In both, Divola sometimes photographs the interior of the building as he finds it, but sometimes he intervenes, using spray paint to make repetitive marks on the walls; dots, straight or squiggly lines, and circles in silver, black or red. And in both, Divola’s longstanding preoccupation with gesture is traceable, his own marks and interventions playing out alongside the gradually increasing dilapidation of the buildings he chooses as sites for his photos. Fi Churchman

David Claerbout, Dark Optics at Sean Kelly, New York

27 April – 4 June

The nature of the virtual object, of documentary truth and our access to history have long been key concerns in David Claerbout’s disarming video works, in which complex digital simulation has come to play an increasingly central role. Dark Optics presents the recent Aircraft (F.A.L.) (2015-2021), in which an impossibly shiny but old-fashioned propellor passenger aircraft (a Douglas DC-4 is this critic’s guess) is found stranded on a wooden scaffold in an empty hangar, a bored security guard guarding it from nobody much. The glossy aircraft is a simulation, presented in neurotic, inert detail, speaking to the disintegration of materiality and our faith in images in the era of deep-fakes, where even twentieth-century optimism of air travel for all is reduced to a virtual collectible. The new The Close (2022), meanwhile, recreates a piece of 1920s documentary film, full of jumps, scratches and speckles, depicting the everyday goings-on in a grimy working-class street somewhere in Europe. Finally focusing on the stilled figure of a little boy, impossibly captured in ‘time-slice’ photography from every angle, The Close offers a sort of redemptive fiction of the photographic image’s access to reality, like a wormhole between our time and a century ago. J.J. Charlesworth

Marcel Duchamp at MMK, Frankfurt

2 April – 3 October

The old dude may have been dead for over five decades, but as art and artists become ever more insistent that art has a role and and a purpose (usually ‘urgent’) – such as advocating for the environment, representing marginalised voices, contesting patriarchy – taking a moment to go back to the godfather of artistic scepticism and free-thinking might be worth the trip to Frankfurt. MMK’s retrospective assembles pretty much the entirety of Duchamp’s interwar oeuvre, from his art-object-abolishing readymades, via his gender-bending alter-ego Rrose Sélavy to the epicly strange The Large Glass (1915-1923), along with publications, ephemera and rare works Duchamp privately made when he had supposedly given up making art in the postwar decades. Questioning everything about the nature of art, seeing, thinking, creativity, sex and what makes humans human (rather than mere machines), Duchamp set ideas in motion that are still coursing through art now. Though what Duchamp might have thought of the earnest artists of today, and the vast art-industrial-complex that sustains them, we can only imagine. J.J. Charlesworth

Elmgreen & Dragset, Useless Bodies? at Fondazione Prada, Milan

Through 22 August

What are we for, anymore? That might be the overarching question for Elmgreen & Dragset’s newest exhibition-cum-installation, where it seems most human beings have just recently left the building, while those still there find themselves in various precarious and vulnerable situations, or are starting to turn into lifeless effigies of themselves. A chilly takeover of every space at Fondazione Prada, Useless Bodies? presents unnerved visitors with simulacra of a sculpture atrium, a bleak office-cubicle floor, an abandoned fitness centre and swimming-pool, and a less-than-comforting futuristically sterile designer domestic interior. ‘Our bodies’, say the artists, ‘are no longer the main agents of our existence… In the nineteenth century, the body was the producer of daily goods, whereas, in the twentieth century, the body’s role became more that of the consumer. Twenty years into the twenty-first century the status of the body is now that of the product – with our data gathered and sold by Big Tech.’ Art exhibitions, of course, are a kind of vanishing-point of the world of work, industry and production that we (at least in the post-industrial West) are fast leaving behind, and with the cultural retreat into everything virtual, maybe physical artworks and their places are becoming spectral. What use are art spectators, might be the duo’s sly and disquieting conclusion… J.J. Charlesworth

Emii Alrai, The Hepworth Wakefield, Yorkshire

7 April – 28 August

For Iniva’s Future Collect programme (art commissions which look to change the conversation around the practice of collecting) artist Emii Alrai presents a sequence of hand-blown vessels – recalling the form of funerary urns, their surfaces marked by scars and seams – in a new installation at the Hepworth Wakefield. Alrai’s works – often premised on the imitation of ancient artefacts – consider the dynamics and contradictions within Western museological displays and collections, drawing on mythologies from the Middle East as well as oral histories which reference the artist’s own Iraqi heritage. En Liang Khong

Poklong Anading, light, growth, residue at Silverlens, Manila

7 April – 7 May

Writing in ArtReview back in the summer of 2018, Anading voiced some baldly existential concerns about the role of the artist in society: ‘Sometimes I think I shouldn’t be part of the art scene: why are we making art rather than fixing society? The more art that is made, the more it spreads and the more problematic it becomes: we talk about a problem rather than addressing it.’ Here the Filipino artist looks back over his past output, executed in a variety of media, both through the lens of the exhibition’s title and as a commentary on the evolving conditions of the Anthropocene and humankind’s problematic relationships, not just with art, but with everything around it. That’s not to say that the show is going to be one big bummer. More that it looks beyond art as an expression of the consumption and deployment of materials and rather towards its ability to describe and engineer relationships between people, materials and the wider world. Understanding such relationships seems a first step in addressing some of the problems of the world. Nirmala Devi

Ukrainian Postcards, by Owen Hatherley, Repeater Books, £7.99

Among several excellent books out this month, Owen Hatherley’s new ebook, in aid of Ukrainian workers and artists, draws on the ever prolific architecture critic’s writings on Ukrainian urbanism over the past decade – an important heritage and built landscape now under threat. En Liang Khong

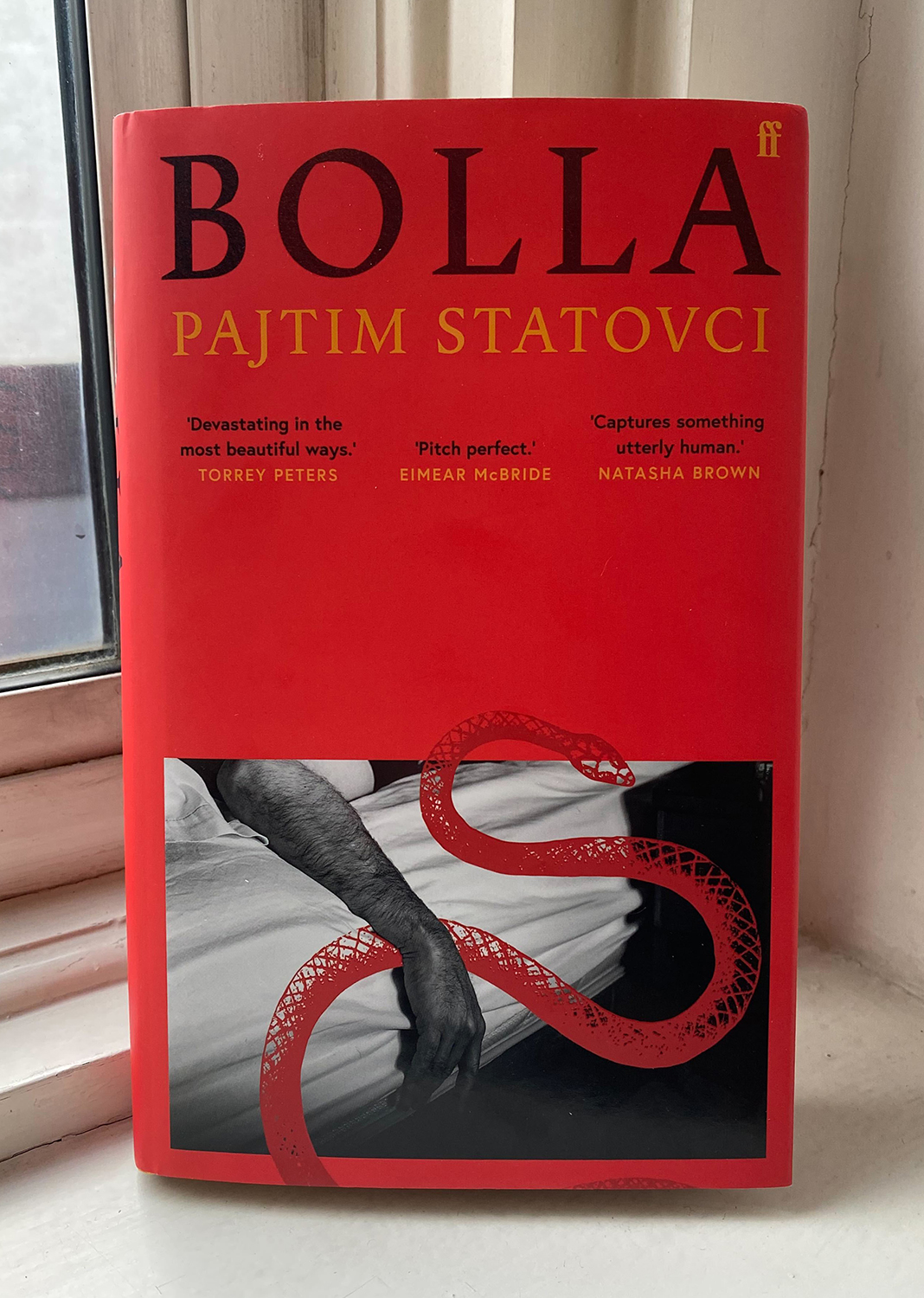

Bolla by Pajtim Statovci, Faber & Faber, £14.99

‘I have held a friend’s heart in the palm of my hand, I have thrust my hand into a chest ripped apart by bullets, grabbed a torn aorta, slippery as an eel, felt the vertebrae of the spine like teeth against my knuckles, rested my fingers on the lungs like wet pillows.’ Bolla begins with a diary entry. It reads hastily in long sentences – a tumble of thoughts – as if the writer is no less able to stop the spilling of these words than stem the dreadful memories of his experiences of the Kosovo War and the atrocities he experienced as a soldier and medic. These written entries (composed between 2000 and 2002, a short time after the war has ended) punctuate a narrative that largely focuses on Arsim, a young Albanian man who lives in Pristina with his wife. But theirs is a loveless marriage – used as a shield for his homosexuality. He meets Milos, a medical student (and author of those entries), and they embark on an affair only to be separated as the rising tensions in the region escalate into warfare. A tale of forced migration, PTSD, armed conflict and the navigation of gay relationships at a time when these were illegal, this third novel of Kosovo-born Finnish author Statovci presents a timely spotlight on the horrors and longlasting emotional effects of war. Fi Churchman

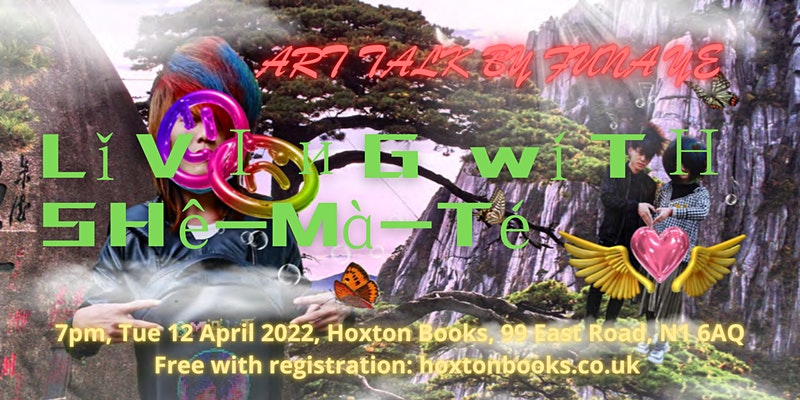

Talk: Funa Ye, Living with Sha-ma-te, Hoxton Books, London

12 April, 7pm

Funa Ye discusses her latest research on China’s Smart/Shamate subcultural phenomenon: a ‘post-Internet folk art force’ that has emerged among a rural generation born in the 1990s, known for its vibrant, clashing aesthetics – drawing on everything from punk and goth to Korean pop culture. The artist will talk about her collaborations with members of the movement, and where it might go from here. En Liang Khong

Nalini Malani, In Search of Vanished Blood (2012) on SOUTH SOUTH VEZA

Through 10 April

Normally shown as a six-channel multimedia installation Malani’s seminal work is available as a single channel online version for a limited time on the South South Veza platform. The title and the work as a whole draws on the words of Pakistani revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Featuring the artist’s signature combination of layered live action, animated and still imagery, the work, which manages to be violent without depicting any overt violence, is a howl of rage at the treatment of women in Indian society and, indeed, society at large. Nirmala Devi