Lévy Gorvy, New York, 7 September – 21 October

Pat Steir’s paintings are, in the artist’s words, “made by gravity”: since the late 1980s, she has almost exclusively employed a process of pouring and dripping layers of thinned oil paint onto upright canvases tacked to her studio wall, allowing the pigment to work its way down the surface. Inspired in part by her friendship with John Cage, Steir’s turn to poured paint was a means of “remov[ing] ego from the work” by allowing the paintings to ultimately create themselves. Steir plans out the order in which she will apply colours, the viscosity of the thinned paint for each layer, and the duration of the pour, but the end results are dictated as much by chance and the elements – the humidity in the studio on a given day, for instance – as the artist’s own intent; once the paint hits the canvas, her control over the situation ends. Though her works are formally in dialogue with Abstract Expressionism, she explicitly rejects the ‘expressionist’ part of that equation. (As she recently quipped in an interview with Sylvère Lotringer, “if you have to express yourself, you should see a therapist”.)

Kairos, Steir’s first New York exhibition since joining the bluechip gallery Lévy Gorvy in 2016, features 12 recent paintings, mostly employing an ethereal, icy palette of light blues, greys, pinks and greens, alongside shimmering silver and gold. All of the paintings are organised around a central vertical split, but Steir achieves remarkable variety within this simple compositional format. Some paintings seem to cleave at the centre, revealing underlying strata of layered paint beneath the surface. In Lila Judith (2016–17), an overall field of pinky purple, punctuated with narrow drips of white, opens up to reveal a streak of black. At a distance, Morning (With Red Line in the Middle) (2015–16) appears to consist of thin rivulets of black paint dripped over a white ground, bifurcated by a forceful strip of black. Up close, it becomes evident that the opposite is true: the ‘drips’ of black are cracks in the layer of white on top, pulling apart at the middle. The effect is elemental, like tectonic plates shifting, or sutures coming undone.

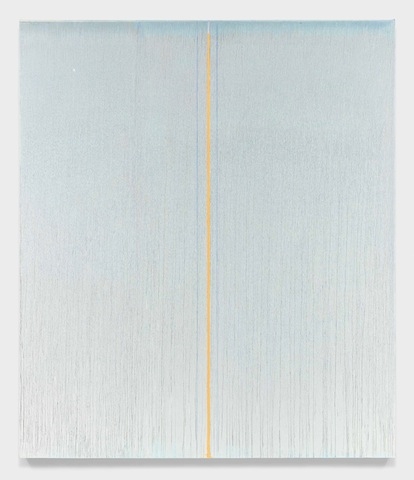

Others have a more emphatic, Newmanesque ‘zip’ dividing the canvas: in Sweet Grey (2016–17), for instance, one of seven smaller, square canvases on the gallery’s second floor, two parallel streaks of red cut down the centre, emphasising the tonal inversion between the two halves: on the left, lavender overlaid with cascading passages of white and grey; on the right, silvery grey tinged with lavender peeking through from underneath. One large painting, Angel (2016–17), is unlike the rest, with a precise, taped-off line of tangerine orange resting atop a whitish ground – a homage to Steir’s late mentor, Agnes Martin. In its deviation, this painting seems to offer a key to how to understand the rest, foregrounding the palpable energy Steir creates at the seams.

From the December 2017 issue of ArtReview