“Life is chaos – we all know that,” says photographer Tim Walker as we sit at the large dining table in his East London studio. The principle is illustrated by a pile of books on the table including both Hieronymus Bosch: The Complete Works (2016) and a handmade version of Walker’s latest photobook, Shoot for the Moon (2019). He opens the latter (he couldn’t wait for the book to be published, he explains) and begins to flick through.

“Those parallel worlds,” he says, gesturing towards the photographs of fantastical sets for which he is famous, “are very meticulously put together, but they don’t work if that’s all they are. It becomes very stiff and predictable. What I always look for is to create the world and then for the wind to rip through the set and for everything to fall down, or for someone to walk in who isn’t meant to be there, or for the person you’re photographing to turn around to look at something. It’s where something went wrong that makes the photograph stronger and more telling.”

Walker began his career at the age of twenty-five when he was given his first shoot in Vogue – to which he has contributed regularly since – and remains best known for his photographic work in fashion magazines including W Magazine, i-D, Vanity Fair and Another Man. His subjects include models and celebrities from the worlds of film, music, literature, art and theatre, styled in couture and positioned within the ‘parallel

worlds’ of his unrestrained imagination (often realised by longtime collaborator and set designer Shona Heath). Think Cate Blanchett standing in a moonscape surrounded by dead tree trunks, strapped into a pair of skis, outfitted in a Comme des Garçons dress with hair styled by Julien d’Ys. The photographer himself is quiet and unassuming.

“Photographers are trying to make sense of this world, put a frame around it,” he continues, drawing a rectangle in the air, “so that they can garden within the walls and make everything look pretty… but they know that outside those walls it’s wilderness. As a photographer you’re trying to take screenshots of life and show that it resonates with your sense of what is beautiful. But the decisive moment is chaotic.”

Walker cites as inspirations Richard Avedon, Horst P. Horst, Irving Penn and Helmut Newton, and he’s keen to understand what it is that makes some fashion photography, in his words, “transcend its commerce”. He gives the example of Horst’s photo The Mainbocher Corset (1939), which the photographer took the evening before leaving Paris for New York in anticipation of the city’s invasion by Nazi forces. “The way she holds her arm up as she looks down, with the lace trailing behind her. I think, as a photographer reading another photographer’s work, that he would have started the shoot in profile, and then maybe he pulled the camera back and realised all the lace and shadow and light were falling a certain way – that’s what makes the picture. And you couldn’t recreate the urgency of that moment.” It seems, then, that the photographer’s self-awareness when making the image is among the things that makes it possible for the image to ‘transcend’ its status as fashion advertisement.

“As a photographer you’re trying to take screenshots of life and show that it resonates with your sense of what is beautiful. But the decisive moment is chaotic”

It’s hard not to be swept up by Walker’s enthusiastic romanticism (also apparent in the title of another photobook, Wonderful Things, which accompanies his current exhibition at London’s V&A museum). Particularly when he talks about how he found a way to articulate his own “visions of beauty” through his camera – tiny scenes from Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1500), for example, recreated with alabaster figures reclining in translucent balls surrounded by giant spiky flowers, fruits and pearls. But the sense remains that the static images he presents are still only fragments of the worlds he conjures in his mind. So it’s revealing that, alongside photography, Walker has also made short films and videos. From his earliest, independently made The Lost Explorer (2010) – inspired by Patrick McGrath’s 1988 short story collection Blood and Water and Other Tales – to collaborations like The Mechanical Man of the Moon (2014, for Vogue Italia) and a video for Björk’s Blissing Me from her 2017 album Utopia, the medium allows him to expand his imaginary worlds.

For Wonderful Things, Walker was invited to explore the V&A’s collections and produce a series of photographs that respond to objects and artworks in the museum (including a stained-glass window, an embroidered casket and a photographic reproduction of the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry). As with two previous solo exhibitions, also in London, at the Design Museum in 2008 and Somerset House in 2013, the exhibition at the V&A includes props from the fashion shoot. This time, however, Shona Heath has also completely transformed the interior of the main gallery spaces, so that the exhibition moves from bright white walls that appear to be melting from the top, to the architecture of a Gothic church complete with a skeletal vaulted ceiling; from a kitschy pink domestic interior and an ultraviolet garden to rounded walls padded with fabric. Walker’s photographs seem to move beyond the frame in which they are shot, inviting the viewer into those parallel worlds and inspiring the sensation of moving through flickering, waking dreams.

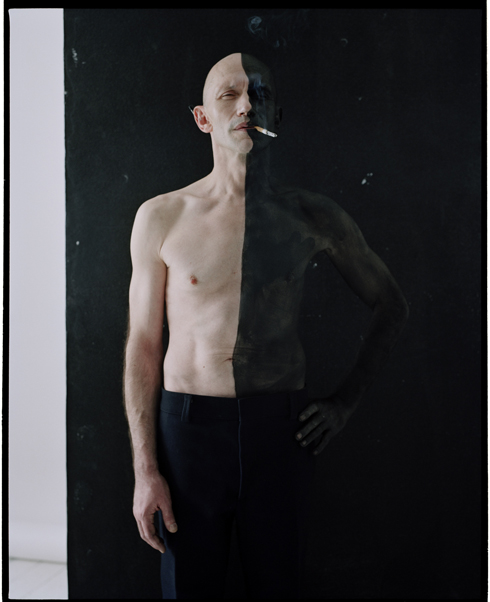

Walker stops at a photograph in Shoot for the Moon of choreographer and dancer Michael Clark, taken in 2016, in which one vertical half of his body is painted black. The plan was to photograph the subject in profile, against a white backdrop, Walker says, but then Clark “stopped to have a break and lit a cigarette, and was just standing there [front on, against a black background]. You weren’t meant to see that, but it became the picture.”

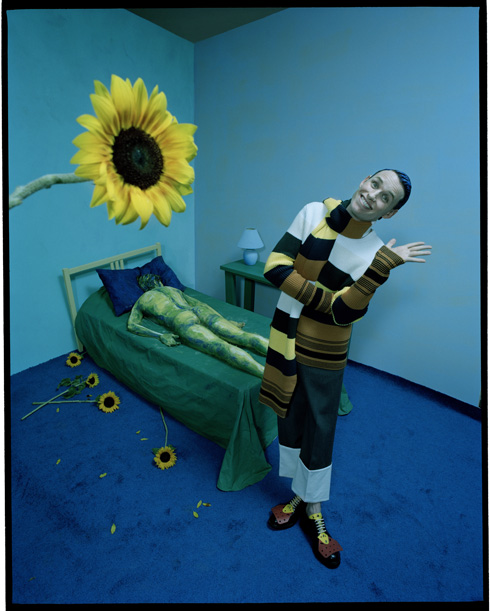

These moments of chaos, both accidental (in the sense of being unscripted) and conscious (in the sense that Walker chooses to take the shot at that instant), are characteristic of his most successful work. Take, for example, a pair of models dressed as geishas operating Japanese-developed Gen h-4 flying machines: the already absurd scene that combines highly embroidered traditional Japanese kimonos with new technology against the backdrop of an industrial landscape is made more so by the geisha on the right, whose smile and wave o set the severe gaze of her partner. “If I’d said to her, do a funny grin and wave at the camera, it wouldn’t have worked. It was just so truthful. She felt momentarily ridiculous in an entirely ridiculous situation and she authenticated that photograph for me,” Walker explains. “I’m not selling anything but a ‘dream’. I’m hyperaware of consumer society. [I know that] when I’m making pictures like these, the only reason a photograph like this ends up in a magazine is because the model happens to be wearing couture. But it’s also absurd.”

Is the truth that Walker seeks to be found in such cracks in the facade? The artist says he learned how to extract a performance from Avedon, for whom he worked as an assistant after graduating in 1994, but that he has discovered through his own practice that the successful photograph is “either the first picture, or the one after four hours of shooting.” Whether it’s Eddie Redmayne channelling a bumblebee, a heat-exhausted model sitting hunched over the edge of a UFO during a break, or the disembodied hand of someone behind the scenes straying into the photo, the ruptures in the artifice elevate the best of Walker’s constructions.

Michael Clark “stopped to have a break and lit a cigarette, and was just standing there [front on, against a black background]. You weren’t meant to see that, but it became the picture”

I ask him about his need to construct fantasies and alternate worlds. He quietly replies, “I find it reassuring for its darkness, or its strength, or its acute ‘prettiness’.” And then I ask him what he needs from his photographs: “Truth. I need the truth.” Later he says wryly that “fiction needs truth in it – in something that’s so fake”, looking down at a photo of the artist Setsuko Klossowska de Rola holding an oval mirror, its face turned away from her. If that’s the case, why does he so consistently look for the ‘beautiful’, or as he also translates it, the ‘odd’, ‘fantastical’ and ‘fun’ – as opposed to other photographers, who take as their subject quotidian life? “It’s medicinal,” he replies. And what does this medicine counteract? He pauses. “It’s a medicine for when human behaviour lets you down, or human actions are disappointing. When you’re seeing a lot of the questionable sad aspects of humanity: the mean, vain and consumerist. But without that darkness, you can’t experience the light.”

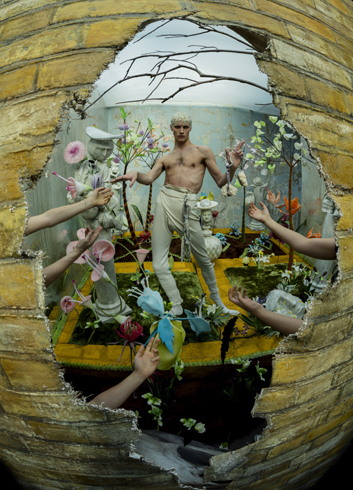

Walker’s exhibition features a series titled Soldiers of Tomorrow (2018). Based on a photo reproduction of the Bayeux Tapestry, it depicts models sitting, kneeling or standing. The walls of the room suggest the patterns of medieval gambesons or, more sinisterly, the padded cells of psychiatric hospitals. They’re dressed in a combination of soft textiles studded through with steel nails, or wrapped in bandages, or wearing knitted balaclavas and headwear, and shot with a fisheye lens that adds to the warped sense of reality. Another series, Box of Delights (2018), is inspired by a seventeenth-century embroidered casket at the museum, which is displayed alongside the photographs in a specially constructed, wallpapered room designed by Heath. Covered in satin, silk and metal thread, it contains an intricate garden scene with tiny apple trees and carved figures. The photographs show, through a hole in a fake brick wall, disembodied arms reaching out to a man in white long johns. He stands in an artificial garden of green velvet and giant flowers, surrounded by grotesque versions of the casket’s carved figures.

Both series depict a fabricated world in which chaos can be contained. Warfare is confined to padded cells; a young man’s desire to a garden. These are spaces of managed disruption. “If you can’t see a utopia in our existence,” the photographer states, “why can’t you make one?”

Wonderful Things is on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, through 8 March; Wonderful People is on show at Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, through 25 January

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview