Part of the Labyrinth is itself multipart; the same theme will stretch over a second edition of the biennial in 2021. That one biennial is in this case actually two, separated yet the same, is, according to curator Lisa Rosendahl’s exhibition statement, aligned with the idea of ‘entanglement’ as a way of thinking about the world in terms of mutual and interconnected relationships, rather than as a range of rationally separated entities. This idea also links to Gothenburg’s own history: the holistic worldview was, according to Rosendahl, defeated in Europe by the work of seventeenth-century philosophers such as René Descartes in the same period that Gothenburg was established.

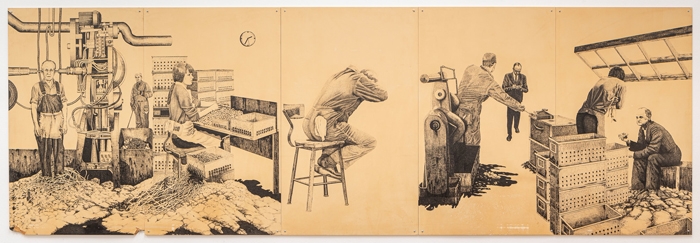

Part of the Labyrinth relates this philosophical scope to some very local narratives. Knud Stampe’s stunning largescale ink-drawing triptych Väggteckning (1970–71), which has long hung in the union clubhouse of the Swedish Ball Bearing Factory, is now on display at Göteborgs Konsthall. Its multitude of 5mm-ink-pen lines advertise its lengthy gestation, monotonous labour comparable to Stampe’s depressed-looking factory workers, depicted here surreally out of context against the drawing’s white background. Väggteckning is presented in a small, tightly installed room that creates both intimacy and distance between viewers and the art, the works’ display suggesting a museological installation. This doubleness reminds us that art, and the white cube, can alienate as well as evoke ‘entanglement’.

Next to Stampe’s work, Rikke Luther’s Concrete Nature (2018–19) is a documentary-style video revolving around concrete, a material made since antiquity but manufactured on an industrial scale from the nineteenth century, later enabling the buildings of the European and American welfare states. This political project, Luther suggests, charged concrete with ideological agency, since it enabled modern largescale premises for housing political and social institutions (municipal centres, healthcare institutions, housing projects) intended to distribute wealth and guarantee social security. Another work by the artist at the Natural History Museum, The Planetary Sand Bank (2019), is a triptych of screenprinted canvases mimicking the pedagogical aesthetic of its host venue, explaining the legal and political forces in play when extracting sand, and the process’s environmental effects. Luther’s two works deal with potentiality and progressiveness, and, simultaneously, the devastating consequences of the same modernity.

At Röda Sten Konsthall, contrariwise, there’s a more utopian tone. For example: Åsa Elzén’s Transcripts of a Fallow (2019), a ‘transcript’ of the large carpet Fallow, created by Maja and Amelie Fjaestad in 1919–20 for the Fogelstad Group. The latter promoted progressive ideas of feminism, design, farming and ecology, the concept of ‘lying fallow’ standing for sustainability: to let rest, reuse and coexist with nature rather than live from it. Elzén’s piece connects historiography with the practical knowledge of handicraft and agricultural traditions.

A similar interest in earthly time underwrites Susanne Kriemann’s Canopy, canopy (2018), an installation made from fabric coloured by plants and soil gathered near an abandoned German uranium mine. There, the plants catalyse and clean the poisoned earth. Here, their radioactivity makes the fabric change colour during the exhibition, like a developing photo. The link to photography as industrialised technology based on resource extraction – articulated in Kriemann’s previous works – is, however, lost here. What remains functions more as a metaphor for photography.

Sometimes, then, the works in the biennial fall into the trap of simplification, not doing justice to art’s entangling capabilities. More often, though, they both uncover a contradictory modernity – one that prompts us to dream of a better world while simultaneously destroying the planet’s fabric – and give historical examples of alternative models for rethinking man in an ecological and social context, suggesting how to act in order not to forget that we are always, already, part of the labyrinth.

Part of the Labyrinth: Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art, 7 September – 17 November

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview