Artist and educator Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s multidisciplinary practice engages with both the histories of institutions and the narratives they house. Her material is history, and she mines library stacks, archives and vernacular photography for her black-and-white collage installations that paste fragments of photocopied images and texts into the corners of rooms and across walls. As a black Muslim woman, Rasheed’s work often focuses on the absence and constraint of these identities and histories. ‘How do I create environments and opportunities that invite a nuanced, rigorous, ongoing engagement with histories that have been flattened and singular?’ Rasheed asked herself in the broadsheet published to accompany her installation at the New Museum in New York last year, which included publications related to the history of black alternative educational institutions and publishing in Oakland.

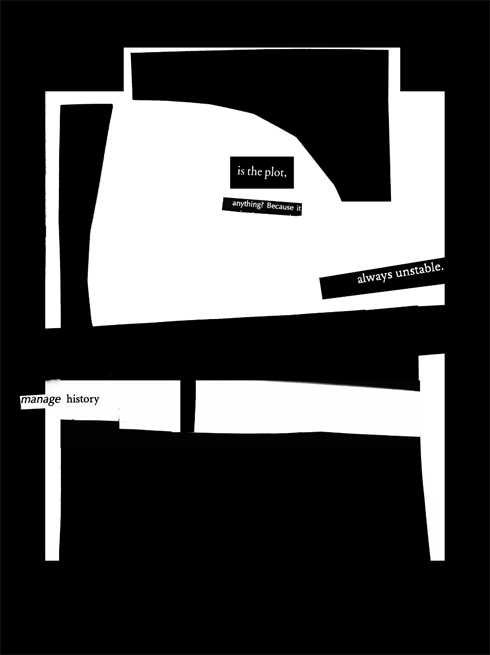

Her current installation at the Brooklyn Historical Society, An Opening – a translation of the title of the first chapter of the Qur’an – uses the society’s ‘Muslims in Brooklyn’ oral histories archive (comprising over 90 personal accounts collected during 2018 and 2019) as source material. The small gallery’s bright teal walls are scattered with framed inkjet prints, hung at varying levels, with scraps of collaged papers affixed directly to the wall, tucked into corners, lined up in rows and stacked at the edges of frames. Together, the prints and wall collages read like concrete poetry: ‘transatlantic almost misplaced the words’; ‘one feels the urgency’; ‘she read unfamiliar “terminology”’. Language fills the room, running across corners and forcing viewers to move with the words as well as read them. The prints similarly abstract language, with excerpted photocopied words and lines of instructional books dancing around the edges of geometric shapes. More Pronounced (2019) shows a central black triangle against a white back- ground, resembling a geometry lesson. It doesn’t include a mathematical formula, but instead the oddly spaced text ‘8. more pronounced’ and ‘life’. The suggested instructional quality of the prints and wall texts – heightened by the knowledge that Rasheed is involved in education and curriculum building – lends the gallery an immersive classroom atmosphere.

Visitors carry an iPhone with headphones through which they can hear selections, triggered by the artwork they’re facing, from the oral history archive. “They get gifts because we do extra gifts for other children as well; you don’t have to be Muslim,” one woman explains about the Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr celebrations as viewers look at More Pronounced. The range of stories and voices included in the exhibition reaches beyond the one-dimensional presentation of a religious and cultural community. The link between the audio and visual texts is nonlinear, with some words echoing in both, like the print that reads, ‘messy / words / happened first’ in a corner of the room where one hears a young man explaining, “Because we’re messy. You know, some of us don’t practice.” But most are tangentially linked, if at all – the audio clips weaving in and out of each other. Standing in the centre of the gallery, you hear multiple clips at once, a chorus of ‘ums’ and distant voices as the phone swings. Hearing them together rather than reading them, or even listening in a library, allows for unexpected connections. The installation offers and demands openness: visitors are asked to put on these headphones and to immerse them- selves in a culture that may not be theirs, and to be open to a nonlinear way of listening, reading and learning.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: An Opening at Brooklyn Historical Society, New York, through 30 June 2020

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview