The Museum of Modern Art has long been seen as the artworld bastion of white male privilege. Its formalist story of modern art, as Carol Duncan argued in her 1989 essay ‘The MoMA’s Hot Mamas’, presents a male spiritual quest fought out over the nude – often fragmented – bodies of lower-class women (models, prostitutes and lovers). It took a sizeable donation from a wealthy woman patron earmarked specifically for spending on exhibitions of women’s work for MoMA, in 2009, to present the first solo show by a female painter, Marlene Dumas, in 30 years. The museum’s historical record on racial diversity is just as awful. But not anymore, it seems. The new MoMA loudly asserts that it has put all this in the past.

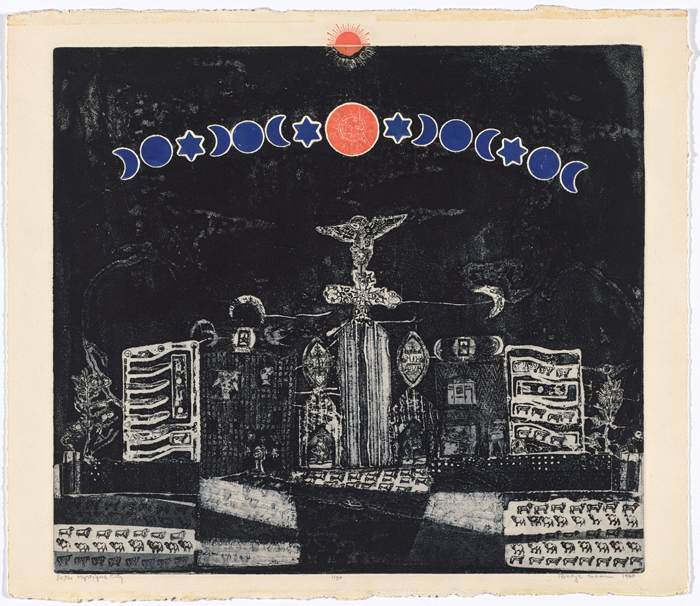

The two modest solo exhibitions for the inaugural rehang are both by black artists. A long-overdue presentation of early work by the African American Betye Saar, best known for assemblage (but here we also discover her roots in printmaking), and an exhibition of paintings by the Nairobi-born Michael Armitage. The permanent collection – presented in the familiar three temporal chunks, 1880s–1940s, 1940s–1970s, 1970s–present – has been reshaped to foreground many more works by women artists and to gesture beyond a Euro/US-centric narrative. And a temporary exhibition of contemporary art, Surrounds: 11 Installations, includes artists from all the world’s continents. It sometimes feels like the curators were shadowed by an equal-opportunities committee prodding them to include the correct quotas of this or that demographic. But given the institution’s record, something seriously needed to shift. How these changes are implemented is not always successful, but on balance, it’s stimulating to see fresh and less familiar works in dialogue with the canonical.

The effect of the architectural renovation feels very much like the old MoMA with more room to breathe. The surprise views out onto the city now also include open-air rest stops and interior viewing areas to sit and take in the layers of Midtown architecture. The major overhaul, however, is in the display of the works and the flow of the exhibition narrative.

Curators from all the divisions of MoMA collaborated to rethink the presentation of the permanent collection. The separate galleries dedicated to photography, book arts, architecture, design and prints and drawings have been overtaken to present a massive integrated permanent collection. A theatrical lighting rig has been built in one of the postwar galleries, suggesting that performance will also feature in exhibitions. But not yet. The sound sculptures by David Tudor currently occupying this space operate as conventional objects, while the eruption of live bodies in the dead museum remains to be seen.

The most daring changes to the integrated permanent collection are in the 1880s–1940s section, where Alfred Barr’s formalist narrative long defined a linear evolution for modern art. We are no longer corralled into a single route from one gallery to the next – Cubism leads to Futurism, to Constructivism, etc – but at a certain crucial point in the interwar period the galleries divide, opening up a choice of alternative paths. As a rhetorical device, this works well in the 1880s–1940s, whereas in the 1940s–1970s spaces it seems more random, confused, suggesting a bland pluralism. The smaller contemporary segment, for its part, is less freighted by historical narratives of chronological progress, making the choice of different routes seem much more natural.

The 1880s–1940s galleries have been reshaped in the most conceptually rigorous and imaginative way, and a call to think history differently is also signalled in select interruptions by postwar work, mostly by women. We first encounter this in the gallery dedicated to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Hanging the African-American artist Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20: Die (1967) in this gallery was a high-stakes bet that paid off. Ringgold’s blood-splattered scene of urban violence, showing white and black men and women, infant boys and girls, with limbs crisscrossed and entwined against a gridded grey ground, is a provocative and generative counterpoint to the MoMA masterpiece. The fate of Picasso’s 1907 painting as modernist landmark is almost wholly indebted to the museum. Its first-ever public display was at MoMA when it opened in 1929. Since taking up a defining place in the museum’s modernist narrative, Les Demoiselles has generated reams of pages of analysis that jostle to reconcile the painting’s conflicting registers of sexual, pictorial and postcolonial meaning. While Ringgold’s American People has a closer affinity with Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which was on long-term loan to MoMA from 1939 to 81, it holds its own in the gallery and generates productive questions about how we encounter artworks in new ways at different historical moments.

In the gallery dedicated to Picasso’s great rival, simply titled ‘Henri Matisse’, a repetition of this contrapuntal historical move is less successful. Although Alma Woodsey Thomas’s Fiery Sunset (1973) offers an important continuity with the colourist preoccupations of Matisse’s work during the early 1900s, the awkward corner position and relatively modest scale finds Thomas’s painting visually diminished and its presence limited to pedestrian notions of influence.

The most significant shift in the master narrative of modern art happens before we encounter these gestures of feminist backtalk. We move from the Postimpressionist beginnings of Modernism into a gallery dedicated to early photography and film before arriving at Cubism. This is an important addition to the museum’s larger narrative, and it is one of the most successfully curated individual galleries. The two acknowledged ‘fathers’ of photography, Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot, are displaced in favour of the offbeat British French pairing of Anna Atkins and Hippolyte Bayard. The former produced the first photobook using the cyanotype process, and the latter’s salt-print method became widely used, but his personal success was overshadowed by the showmanship and acumen of Daguerre. This gallery is not so much a didactic account of the story of photography’s invention as a demonstration of the expansive and pervasive cultural impact of its heterogeneous deployment and use.

The moving image does not lend itself as easily to exhibition display, and the inclusion of segments from two early films, an ‘actuality film’, Interior N.Y. Subway, 14th street to 42nd street, from 1905 (a year after the subway opened) and the earliest existing film featuring African-American actors, the 1914 Lime Kiln Club Field Day (with famous blackface performer Bert Williams), can only really operate as placeholders for a complex yet untold story. Both film and photography have their own heterogeneous histories and they therefore remain subordinated here – or play colourful cameo roles – in a narrative where painting and sculpture are still the lead protagonists.

While the anxious placement of wall plans to map routes through the 1940s–1970s galleries signals a less confident conceptual understanding of the new spatial flow, in the 1880s–1940s gallery, the segue back to the alternative path is beautifully resolved. This breach in art historical logic is definitively scrambled by a packed one-room temporary ‘Artist’s Choice’ exhibition by the painter Amy Sillman. Titled The Shape of Shape, and combining a broad selection of works from across the whole collection according to an abstract formal category, it allows for playful juxtapositions of typically unrelated works in a layered three-dimensional arrangement. Breaking with conventional methods of display, with multiple images on the wall and others propped up on a two-tier platform in front, the display’s effect is of a stylised storage area or a nineteenth-century gentleman-collector’s study. As such it echoes the creative labour involved in rehanging the collection we have just encountered, including the confrontations with establishment masculinity. It also declares that the notion of formal affinities between works is not the sole property of a conservative masculine past but is how many artists think and make.

When I asked around prior to visiting the museum to write this review, the consensus among my art historical colleagues seemed to be that MoMA had abandoned art history. I do not think this is the case. The political present is indeed palpably felt in this earnest rebranding of the museum as a cultural statement against the ideology and values of Trump. At the same time, it is also a serious reckoning with its own institutional history of discrimination, with its own past. It will be interesting to see where MoMA goes from here.

The New MoMA, Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 21 October

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview