Edited by Ossian Ward, Lisson Gallery, £60 (softcover)

‘On the outside a book is part of the world of human appearances, but inside it is governed by a code.’ So says John Latham in an extract from a conversation between the artist and John A. Walker taken from a 1987 edition of Studio International. Latham is talking about his use of books as a material on the occasion of his exhibition at Lisson Gallery that same year. It’s a statement that could apply more directly to the book it’s reprinted in, ARTIST / WORK / LISSON, created to mark another Lisson occasion, the gallery’s 50th anniversary.

This book takes the form of an illustrated alphabetical record of the 150-plus artists who between them have held more than 500 solo shows at the gallery’s spaces in London, Milan and New York, between 1967 and 2017 – Ai Weiwei, Hussein Chalayan, Shirazeh Houshiary, Derek Jarman, Richard Long, Yoko Ono, Joyce Pensato and Andy Warhol among them. Interspersed under the appropriate letters are anecdotes and insights from director Nicholas Logsdail and other senior members of the gallery team, alongside thematic chronologies of group shows and main events in Lisson’s history, that highlight the gallery’s evolution and ethos. For example, there’s F for Family, G for Global, P for Private Views, N for New York and R for Relationships. If the subjects of these insertions are the most random element of the book’s structure, part of what makes it such an interesting read (despite it being 1,152 pages long) is its dogged adherence to its own simple alphabetical and numerical logic. The entry for each artist features a text, in the form of a contemporaneous catalogue essay, review or Q&A, followed by an illustrated chronological record of all their solo shows, plus a list of the group shows in which they have participated. An index of artists featured is at the front and an index of authors at the back. That there are no page numbers assigned to either results in the reader only being able to find individual artists by employing the alphabet, and only finding individual authors by chance.

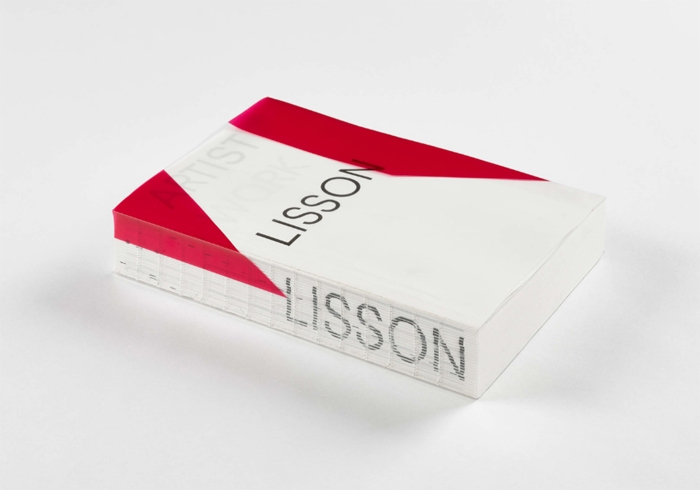

Working with Lisson, the instigator of that logic is the book’s Dutch designer Irma Boom. It’s Boom’s own thin but tough translucent archival paper (IBO One) upon which the book’s pages are printed, giving it, not unintentionally, the dimensions and weight of an old British telephone directory. The clear acetate cover features an artwork in red by Daniel Buren, with limited- and special-edition covers by other gallery artists also available. The other effect of using Boom’s paper is that with each page there is intentional show-through of the one that follows. This is usually something to avoid in book production, but Boom makes a feature of it, as she puts it – like seeing past, present and future all on one page. Some will find this annoying – although not this reader.

Aside from an association with cool design, what makes this more than just a history of Lisson, a gallery established almost by accident by an art student (see B for beginnings) and which champions international minimal and conceptual artists, is the wider picture it reveals about artists and the changing nature of their relationships to the artworld within which they work. This is seen from the pre-email handwritten and often illustrated correspondence artists sent to the gallery, to how and by whom they were written about. It also throws up the question of what it might mean that some artists, Jene Highstein, for example, had only one solo show with the gallery, in his twenties, whereas others, such as Anish Kapoor, have had 16 solo shows and counting. Highstein didn’t disappear from the artworld – he moved back to the States and continued his career there; a reminder that Lisson’s history is only one of many parallel stories.

That this history could be presented at all is because the gallery has maintained its physical archive. There’s a piece of advice once given to Logsdail that he likes to retell: ‘If you don’t look after your history, then you won’t have one’. Helen Sumpter

From the January & February 2018 issue of ArtReview