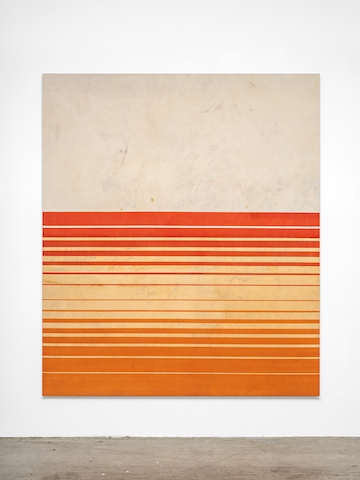

Fredrik Værslev works in series, each of which is founded on an unusual concept for the production of paintings – as is amply clarified by this midcareer retrospective, which brings together nine painting series and one photo series from the last decade. In the central hall, the Canopy Paintings (2011) hang high on the wall – as canopies are supposed to – though sitting flush to it. The striped canvases, reminiscent of 1950s abstraction, are based on awnings in the artist’s childhood home. And just like real canopies, these works have been exposed to ever-changing weather conditions; they owe their natural patina to snow, sunshine and rain. Opposite the Canopy Paintings are the Terrazzo Paintings (2010), painted after the imitation-marble floors found in many Norwegian housing blocks. Although the dots and specks are rendered meticulously and the picture surface is, appropriately, ground smooth, one can’t help thinking of Jackson Pollock’s drippings. Small preliminary studies for the Terrazzo Paintings are placed in several models of simple suburban houses, the Dollhouse Series (2016). Together, these three series testify to Værslev’s main preoccupations: how does abstract painting fit within our everyday environment? And how to employ abstraction to convey personal memories?

Each of the works looks good on its own, but they’re better when seen in a row. The museum’s galleries, with their triangular walls and curved ceilings, are not exactly tailor-made for the display of paintings, but Værslev did not interfere with Renzo Piano’s obtrusive museum architecture. His spatial layout is a grand and elegant gesture that adds surplus value to some of the works. The smallest room contains the largest pieces, the Sail Paintings (2016), loosely based on the sails in the harbour of Værslev’s hometown, Drøbak. Because one of them didn’t fit on the wall, it is hung from the ceiling, floating in space, so one can see the verso of the work as well: it’s as if the painting is mimicking a sail.

Displayed on the first floor are paintings produced with unorthodox techniques. The stains and patches in the Mildew Paintings (2013), for example, are the result of mildew that grew on the primed canvases when they were rolled up and stored outdoors for a period of 12 months: rather than the outcome of artistic control, these blurry monochromes are products of nature. The Trolley Paintings (2012) result from mechanised labour: their straight lines are painted with a device commonly used to mark lines on sport fields. Værslev’s Shelf Paintings (2009), which spun off from the artist’s mother’s desire to have a painting with a shelf for displaying knickknacks, are partly produced by friends and family.

The most impressive room combines the Pyramid Paintings (2015) with colour prints from the photo series My Architecture (2008). The paintings are made of leftover canvases, stitched and stretched on an aluminium frame with a distinct pyramidal form. The shape was inspired by a construction used in the Scandinavian building industry to cover windows when a facade is being renovated. The photos tabulate facades of different office blocks, cannily shot from such an angle that they seem to be part of one and the same building. The combination of these two series articulates Værslev’s ambition to connect painting to architecture, or more precisely, to the urban environment of the Norwegian welfare state in which he grew up. Abstract painting, no longer at the service of modernist progression, is here coming home.

Fredrik Værslev: As I Imagine Him at Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, 29 September – 6 January

From the January & February 2019 issue of ArtReview