Tschabalala Self, Lenox, 2017, fabric, ribbon, painted canvas, flashe and acrylic on canvas 172.7 x 127 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery

Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 6 February – 10 May

Nearly 40 years ago, in 1981, London’s Royal Academy mounted the landmark show A New Spirit in Painting, which spread its wings wide enough to enfold Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol and Jean Hélion, but centred on the then-ascendant Neo-Expressionism and Italian Transavanguardia. Whatever its virtues, in retrospect this was an extremely pale-and-male show. To the extent that Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium is an unofficial sequel – though featuring just 10 artists, the Whitechapel Gallery’s exhibition aims to survey the colour-saturated revival of expressive figurative painting since 2000 – it’ll illustrate how much things have shifted. More than half the artists here, among them Tala Madani, Christina Quarles, Dana Schutz, Tschbalala Self and Michael Armitage, are women. They’re not all European or American or white. The work engages with gender fluidities, race, sex and geopolitics, and it’s often inflected by digital prep work. Stately European males do figure, after a fashion, but we’ll find Paul Gauguin, Willem de Kooning and Eugène Delacroix as subjects of retrospective interrogation rather than reverence. More widescreen reasons for figurative painting’s rebirth, such as a bullish art-market and a weariness with regard to recent trends in abstraction, will likely go unremarked, but this will undoubtedly be a feisty display.

Jacques-Louis David Meets Kehinde Wiley, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 24 January – 10 May

Kehinde Wiley would have fitted nicely into the above show, but save your tears: he’s appearing in his own New York exhibit, facing off against an imposing predecessor. Wiley’s virtuosic paintings, as is well known by now, take the stylistics of European portraiture as an armature for black representation. His figures, poised and hieratic, are exclusively people of colour, wearing sneakers and sportswear, often chosen off the street; though presumably he didn’t just bump into one of his more notable subjects, Barack Obama. The former US president, who he painted in 2018, was pictured seated against a spread of bright, coded foliage –chrysanthemums for Chicago, jasmine for Hawaii, African blue lilies for Kenya – and Wiley typically poses his subjects against such decorative backgrounds, so that even when their poses evoke portraits of Napoleon, there’s a flavour of, say, the portrait photography of Malick Sidibé et al. (And, not infrequently, an undercurrent of homoerotic energy.) At the Brooklyn Museum, in Jacques Louis-David Meets Kehinde Wiley, Wiley’s painting in the museum collection, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2015), is paired with David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1800–01). In Wiley’s painting, Napoleon becomes a black man in camo and Timberlands, while the background and frame incorporate motifs of testicles and sperm (and a self-portrait) in an intertwining of art-historical deconstruction and self-aware machismo. Expect, elsewhere, related works by Wiley, Napoleon-centric works from the museum collection, and a video of the artist on the grounds of Malmaison, Napoleon’s last residence.

The Trees, Light Green…, Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm, 22 January – 29 March

These aren’t the only exhibitions this month to assess how painting has changed, or rather been changed from within, in our still-new, if already exhausted-feeling, century. In Stockholm, The Trees, Light Green: Landscape Painting – Past and Present declares its intentions from the get-go, leaving out the perhaps unnecessary detail that it focuses on Scandinavian art. In play here are several timespans. The older (meaning dead) artists’ practices date from the turn of the twentieth century, by which time industry had rapidly expanded in Sweden and the first national parks were being established. (The Industrial Revolution was also contemporaneous with the popularisation of oil paint.) The exponents in this show include the Impressionism-inclined Julia Beck, the nature-adoring royal Prins Eugen and the moodily expressive Evert Lundquist. The living painters, meanwhile, work in the teeth of climate change, and their landscapes more regularly espouse doubt and anxiety, whether in a relationship to the sublime (Sigrid Sandström’s canvases, which threaten to collapse into abstraction), in the heavy, ominous but suavely daubed vegetation of Jenny Carlsson, or in Sara-Vide Ericson’s ritualistic excursions into the landscape surrounding her Swedish studio. Even when such recent works look relatively bucolic, one might bear in mind that the show is timed to close on 29 March, the day in 2020 when humanity will supposedly have consumed the year’s resources and will be depleting future reserves. Enjoy the painted nature, then, and despair.

Rem Koolhaas, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 20 February – 14 August

Nor, to perpetuate this daisy chain, is Bonniers Konsthall the only institution with ruralism on its mind right now. The 98 percent of the earth’s surface that is not citified is the research focus of Rem Koolhaas’s Guggenheim exhibition Countryside, The Future. Here, the highly metropolitan architect (author, you’ll remember, of Delirious New York, 1978, as well as the architect of the short-lived Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas) uses a ‘multi-sensory’, research-driven installation involving photos, videos, archive materials and a wallpaper display wrapped around the museum’s famous rotunda spiral to consider the silent changes that have been going on outside of cities in recent decades. This, famously, is where the Trump voters are; it’s where vast cattle-grazing lands are (the display clarifies the boggling scale of these); and it’s also, for Koolhaas, a space of potential possibility and change. Expect a focus on China, South America and California, excursuses on artificial intelligence, political radicalisation, global warming, subsidies and tax incentives, and much more. If you’re not sure how all that fits together but you’re at least curious, that might just make you an ideal viewer.

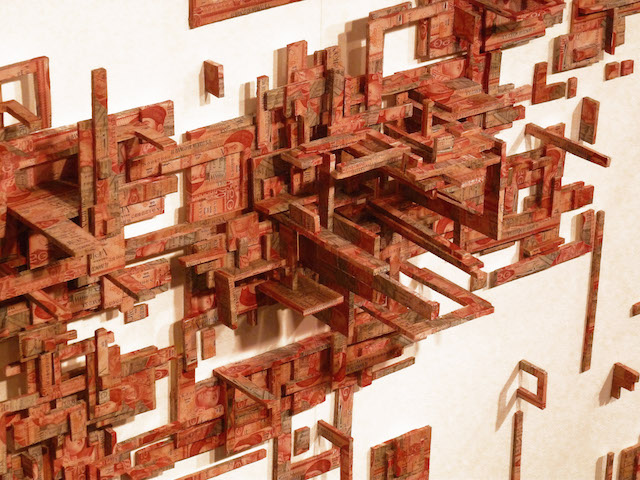

The Supermarket of Images, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 11 February – 7 June

Ninety-one years ago, Walter Benjamin wrote of a moment when we’d reach ‘a one hundred percent image space’. Are we there yet? Images are the means by which not only objects but, now, people are commodified, or elect to commodify themselves. The outcome of this dispiriting trajectory, writes philosopher Peter Szendy – one of three curators of the Jeu de Paume’s new group show, along with Emmanuel Alloa and Marta Ponsa – is, if you will, The Supermarket of Images. (No mention of Guy Debord, but maybe there’s no need.) For Szendy, this new reality of the economics of a life lived, and bought and sold, through images deserves a new word: iconomics. Meanwhile, a spread of artists has been entrusted to articulate the position, including Aram Bartholl, Samuel Bianchini and Máximo González, whose Small Money Labyrinth Project (2013–15) generates collages from out-of-circulation banknotes, turning economics into images. (Hmmm, there should be a neologism for that.)

Bunny Rogers, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 18 January – 13 April

Self-marketing in the visual economy is something Bunny Rogers knows plenty about: the American post-Internet pioneer has explored it thoroughly while moving across media, from photography and video to installation, often appearing in her own work as a kind of composite self that mixes fact and fiction, an interior self and influences from outside. (‘Objective art is impossible,’ she’s said.) Those outside pressures and background psychic stresses, in her work, have included the performative Internet phenomenon of ‘planking’ (which, in photos, she recast as a form of sexual submissiveness), the 1999 Columbine massacre, the existence of online child porn, male My Little Pony fans, and, in the 2017 installation Farewell Joanperfect, the idea of her own death, rendered as the spectacle of her own imagined funeral. American funerals, indeed, are the subject of her four-floor show at Kunsthaus Bregenz: expect lawns, concrete roses and sprinklers evoking school shower rooms – bringing us, inevitably, back to Columbine, 20 years ago now but symbolising a very present-day problem for the US.

Dhaka Art Summit, 7 – 15 February

The fifth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit is, as ever, not for the energy depleted. Stretching over four floors of the Shilpakala Academy in the Bangladeshi capital, it mixes exhibitions (including the Samdani Art Award), panel discussions, symposia and performances via some 500 contributors under the steerage of Diana Campbell Betancourt. The theme holding this year’s edition together is Seismic Movements, which apparently refers not only, as you might expect, to geopolitics, but to shifting readings of history and art history. (‘We continuously work to break down barriers between art, film, craft, architecture, design, research, and institution production to think of new forms of togetherness,’ Campbell Betancourt affirms on the website.) Expect, among other things, an installation by Adrián Villar Rojas made from 400-million-year-old fossils, a multiscreen film by Thao Nguyen Phan exploring a little-known midcentury Vietnamese famine, paintings by Ellen Gallagher furthering her interest in the Afrofuturist mythology of Detroit techno recluses Drexciya, a group exhibition responding to Bangladeshi architect Muzharul Islam, a nine-day film programme curated by The Otolith Group, a ‘festival of connectivity’ organised by Jakarta’s Gudskul and, well, a tonne of other delights.

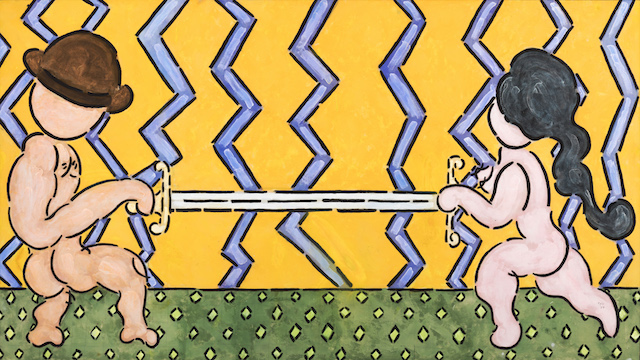

William N. Copley, Max Hetzler, Berlin, 17 January – 7 March

The late William N. Copley had a complicated life, onto which his show at Max Hetzler, The Ballad of William N. Copley, will offer a partial window. First he was an art dealer, trying to sell Surrealism to Los Angelenos who weren’t ready for it; then he was an American surrealist himself – Marcel Duchamp encouraged him, and Copley bought his Etant Donnés (1946–66). His subsequent art career pivoted from a mix of thickly outlined, bright-coloured proto-Pop and folk art in the 50s and 60s to, in the 70s, sexually explicit works focusing on the problematics of male-female relationships, and self-imagined flags – eg for the UK and Russia – that emphasised national issues. In amongst this, up to his death in 1996, he made wallpaper based on that found in American brothels, painterly tributes to prostitutes, and reappropriations of his own earlier work. He also found time to be married six times and predate the contemporary use of the acronym ‘SMS’ in a series of late-60s portfolios of artistic collaborations titled Shit Must Stop. This, you may not be surprised to learn, followed one of his divorces.

Johanna Unzueta, Modern Art Oxford, 8 February – 10 May

‘My mum always said I learned to weave and knit before I learned to read and write. Hands are tools for me and I can’t disconnect that,’ Johanna Unzueta says. The New York-based Chilean artist, now having her first solo show in the UK, relatedly aims to reconnect labour and the human hand – partly, in a restoring of dignity, as a reminder that the factory-produced objects we use, and that we often don’t even go to shops to buy anymore, are very much the product of human toil. As such, her works here – a largescale felt installation, collection of garments, film made in a Chilean textile factory, wall mural and a range of ‘freestanding geometric drawings installed by natural patterns’ – are double-edged. In the relatively luxe conditions of an art gallery, we’re reminded of the difference between industrial labour and artistic labour, but also of the parallels between them – and, somewhere in there, the ubiquity of work and the need to give it value.

Sarah van Sonsbeek, Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, 18 January – 22 February

As befits an artist who trained as an architect, Sarah van Sonsbeeck is interested in space, and specifically its use as a container of sound and silence. Some of this, apparently, stems from an episode with noisy neighbours; she estimated how much of her space the sounds of their sex and arguments were occupying, and tried to get them to pay the appropriate share of her rent. A 2009 work found her making a glass cube to ‘contain’ a cubic metre of silence near a museum; when it was vandalised, she renamed it One cubic meter of broken silence. Elsewhere, she’s made paintings using Faraday paint, which is intended to block electromagnetic signals, and seemingly riffed on silence – and peace – being ‘golden’ in a stream of works that used melted gold bars, gold leaf, and, in 2013, a gold Anti Drone Tent. As with her delicate glass cube, van Sonsbeeck surely knows that such moves are purely symbolic, emphasising privacy and seclusion as pipe dreams, and her works are replete with error, failure, collapse of intentions, all that jazz. Galleries, nevertheless, tend to be pretty quiet spaces, so there’s that.

From the January/February 2020 issue of ArtReview

Correction: An earlier version of this article referenced a past exhibition by Kehinde Wiley at the Brooklyn Museum. As of 29 January 2020, the article has been changed to reflect the appropriate exhibition.