Eugène Delacroix: Liberty Leading the People (1830)

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was the leading Romantic painter of his age. Besides depicting dramatic scenes from contemporary history and literature, he preferred emotional content over rationality in his paintings. His greatest artwork has been cribbed by, among others, a wildly popular Broadway musical and the British rock band Coldplay.

Behold the image of revolution made heroic. This painting, now hanging in the Louvre, represents a pivotal moment in French history – when violent protests led to the abdication of an unpopular king and his replacement by a more liberal monarch. More than that, it is the filter through which all subsequent images of world revolution are seen.

From footage of the Bolsheviks storming the Winter Palace (captured ten years after the event in a filmic restaging directed by Sergei Eisenstein), to UPI photographs of Fidel Castro’s barbudos entering a liberated Havana, to more recent iPhone captures of Libyan fighters during the Arab Spring, millions of similarly romantic images celebrate the glory of armed revolution – almost as if they had been pushed through a single stencil.

Painted by the world’s greatest romantic artist, Liberty Leading the People – like Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War (1810–20) – eschews the traditional heroic narratives of the Greek and Roman past, which up to then had dominated history painting, in favour of the heat of modern events. Delacroix began his most famous painting shortly after witnessing open warfare on the streets of Paris; he finished the more-than-three-metre-high canvas three months later, just in time to show it off at the official 1831 Salon. The mother of all revolutionary paintings – as well as Soviet-style Socialist Realism – Delacroix’s masterpiece stacks up as a morally simplified fable based on real-life events.

No wonder the monumental canvas has drawn comparisons to that other daughter of France that straddles New York Harbor. Like The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World – as the latter was christened by its maker, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, before being gifted to America in 1886 – Delacroix’s striding depiction of a half-nude Amazon is not intended to portray an actual bayonet-and-flag-wielding individual. Rather, the figure serves as an allegory of liberty plumped by the raptures of romantic aesthetic and political ideals.

Delacroix portrays Liberty’s handsome head in profile, like Queen Elizabeth II on a £1 coin; atop it she wears the Phrygian cap, or bonnet rouge, a symbol of freedom that recalls today’s ubiquitous Malcolm X tees. Surrounding her secular highness are several stock characters: a grimy-faced factory worker holding an infantry sabre (left over perhaps from a previous war), a fancy-pants bohemian sporting a hunting rifle and a schoolboy brandishing two pistols. The painting’s not-so-subtle message is that everyone can become a heroic revolutionary. The rub is that Delacroix’s lavishly idealised scenario is only humanly possible in Les Mis (1980).

When corresponding with his brother soon after completing his famous picture, Delacroix enthused: ‘I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her’. Besides confecting an up-to-date version of Peter Paul Rubens’s Consequences of War (1637–38) – without consequences, excepting the perfectly marmoreal bodies over which his revolutionaries clamber – what the Frenchman wrought was a heroic fantasy of egalitarian revolution. Myriad imitations have littered the world ever since.

Édouard Manet: The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868–69)

Édouard Manet (1823–83) is widely considered to properly deserve the phrase Baudelaire coined for Constantin Guys: ‘the painter of modern life’. His groundbreaking works portrayed the nineteenth century in flowering transition into the twentieth. About the Frenchman’s political painting, curator John Elderfield put it best: ‘political art… does not reduce human affairs to slogans; it complicates rather than simplifies’.

Journalism, declared Washington Post publisher Philip Graham in 1963, ‘is the first rough draft of history’. In art, however, things had already gone further: when the painter Édouard Manet tackled history, he served up drafts one, two and three.

Before the idea of making art ripped from the headlines achieved self-evident vogue, Manet set the standard for painting contemporary subjects so directly that they crackled with authenticity. Among his controversial themes – and there were many, including his depiction of a mousy prostitute as a prostitute – one proved especially radical in political terms: the 1867 execution by firing squad of the Austrian archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, who had been installed as emperor of Mexico (the Habsburg family had originally ruled the Viceroyalty of New Spain) by Napoleon III four years earlier.

A naive puppet, Maximilian did France’s imperialist bidding in North America. His rule depended entirely on the presence of the French army; when Napoleon’s troops withdrew, he was overrun by republican forces and quickly captured. On 19 June 1867, Mexico’s pseudo-ruler was executed, alongside two local generals, in the manner of Christ and the two thieves. These events unleashed the nineteenth-century equivalent of a media frenzy – complete with eyewitness accounts, photographs and prints.

Fascinated, Manet recognised in the subject a great opportunity. He had recently seen Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814) at the Prado in Madrid, the world’s first great modern painting about death by fusillade (consider, in this light, Hans Memling’s Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, c. 1475). Mexico’s regicide, in fact, provided the perfect subject for a clean sweep: the French artist could tackle the fustiness of history painting, the conservatism of the Paris Salon (which predictably rejected his final canvas) and, into the bargain, Napoleon III’s authoritarianism.

Painted between 1867 and 1869, Manet’s painting of Maximilian’s execution exists in three versions. One is at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, another at the National Gallery, London, and a third at the Kunsthalle Mannheim. Two of these versions are either fragmentary or incomplete; the third, which is on your left, has had its painterly I’s dotted and its T’s crossed.

Manet’s last Maximilian painting was the only one to be exhibited in public during the artist’s lifetime. In 1879 it was shipped to New York and Boston and billed as a public attraction, with viewers charged 25 cents for the privilege. The business was a fiasco. Eventually, all three compositions were mothballed in the artist’s Paris studio; years later, the early twentieth century’s love of realism rescued them from oblivion.

An astounding depiction of the execution post-factum, the Kunsthalle Mannheim painting casts the viewer in the role of a fascinated rubbernecker: the triggers have just been pulled and the oaths shouted; the rifle smoke is yet to clear; the jury is out on the morality of the execution. One of Maximilian’s dark-skinned generals rears back with arms raised (the pose is lifted from Goya’s earlier picture); the second awaits his own personal bullet with hands crossed in an attitude of beatitude. Maximilian, for his part, couldn’t look more surprised. Death has found him just as he was in life: gullible, wide-eyed and unprepared.

Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia: Tucumán Arde (1968)

Made up of important figures from the 1960s Argentine avant-garde (León Ferrari, Graciela Carnevale, Norberto Puzzolo and Roberto Jacoby among them), the Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia (1966–68) made a single artwork that achieved a breaking point for political art – the choice thereafter became make art or pick up a gun.

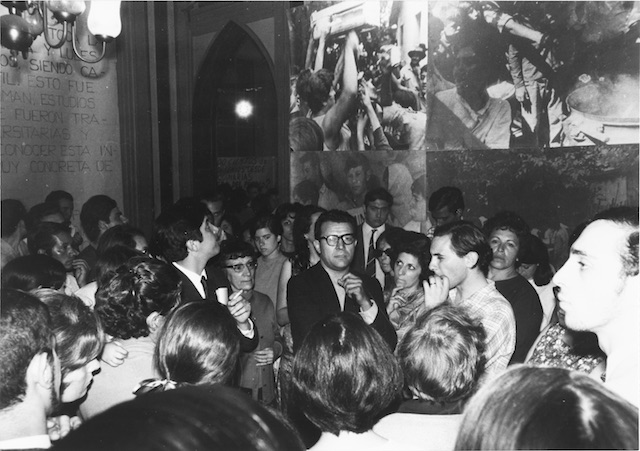

In 1968 a group of Argentinian artists, journalists and sociologists banded together to make the ultimate work of political art. To date, no one is sure whether the experiment was wildly successful or an epic fail.

In response to a laundry list of national and international crises – the Vietnam War, student protests in Paris (as well as in other cities across Europe and the Americas), the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Robert F. Kennedy, the myriad upheavals related to decolonisation and the Cold War, as well as the repression and censorship of the military government of Juan Carlos Onganía – the group banded together to form the Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia, or the Avant-Garde Artists Group (GAV). Their purpose: to turn art from something that hangs tamely on a wall into a force that might shake the foundations of power.

Among the group’s first steps was to affiliate themselves with Argentina’s largest labour union, the General Confederation of Labour (CGT). Next was the establishment of a set of rules: vanguard art would henceforth serve only the oppressed classes instead of an elite public; art could no longer be shown in galleries or museums; real art would aspire to the status of political action, but freighted with deeper significance.

The collective’s manifesto, authored by artists María Teresa Gramuglio and Nicolás Rosa, declared its intention to ‘reveal the fallacious contradiction of the government and its supporting class’; this they planned to achieve through a series of events, interventions and happenings. Their actions included a pair of exhibitions organised in the name of the millions of poor living in the region of Tucumán, the West Virginia of Argentina. The group’s happenings received a fittingly combustible moniker – Tucumán Arde, or Tucumán is Burning.

Rather than stage their shows in museums, the GAV artists installed their works at the CGT headquarters of two major cities: Rosario and Buenos Aires. Together with other left-leaning professionals – among them economists, social scientists and advertising experts – they endeavored to take on the dictatorship’s control directly. Some members travelled to Tucumán to bring back firsthand accounts of the impoverished conditions of Tucumeños. Others remained in Rosario and Buenos Aires to graffiti and paper over the streets with ‘counterinformation’ in imitation of clandestine political cadres.

In Rosario the group exhibited a collage installation by León Ferrari alongside Walker Evans-type photographs of Tucumán’s sugar plantation workers and synoptic charts designed to demonstrate the links between mass misery and corrupt government. There were also audio and video recordings, slideshows, text pieces, a lightwork that flashed on and off to signal the scandalous frequency of infant mortality in the region and an 18-page report explaining the root causes of Tucumán’s poverty. In Rosario, the exhibition lasted two weeks. In Buenos Aires, it closed after just one day, having been shuttered by the government.

According to artist and writer Luis Camnitzer, ‘Tucuman Arde was both a success and a failure’ – chiefly in that art came up hard against the limits of nonviolent politics. After creating a powerful hybrid of art and activism, the collective’s members found they had a target on their backs. A few went into exile. Others stopped making art and joined the guerrilla movement. Several were ‘disappeared’. At least one GAV member, Eduardo Favario, was killed in a shootout with the police.

Gerhard Richter: October 18, 1977 (1988)

Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) is considered by many to be the world’s greatest living painter. His realistic greyscale paintings make a crucial and urgent point today: to see the world in black and white is to live within the contours of extremism.

‘The world is not black and white,’ Graham Greene once wrote. ‘More like black and grey.’ Those words acquire special meaning when considering Gerhard Richter’s painting cycle October 18, 1977, one of the most moving works of political art of the last half of the twentieth century.

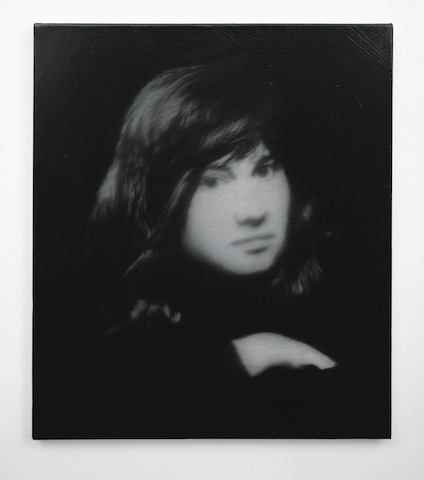

Made up of 15 paintings based on press photographs of four members of the Baader-Meinhof Group, or Red Army Faction (RAF) – a militant group whose bombings, kidnappings, bank robberies and assassinations kept Europe on red alert during the 1970s – Richter’s cycle commemorates the passing of an era. It dramatises the death of four leftwing terrorists, as well as the demise of the idea of Marxist revolution in the West.

Like other cultural products named after a particular day or year – think George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) and On Kawara’s date paintings (1966–2014) – Richter’s canvases are titled after a unique calendar event. On that baleful day, October 18, 1977, the bodies of three principal RAF members, Andreas Baader, Jan-Carl Raspe and Gudrun Ensslin, were found dead inside their cells in Stammheim Prison, in Stuttgart. Though the deaths were officially deemed suicides, there was widespread suspicion that the radicals had been murdered by the German state. A fourth member of the group, Ulrike Meinhof, had also been found a year earlier hanged in her prison cell.

Richter based his subjects’ portrayals on newspaper and police photographs. He rendered the evidence of these photographs unstable: their documentary value was darkened, their reportorial accuracy muddied and their sharp edges blurred via a process of painterly smudging that resembles seeing through a foggy car-window. The results affirm a wavering realism. As Richter himself put it, ‘by way of reporting’, his 15 canvases ‘contribute to an appreciation of [our time], to see it as it is’.

Doubling down on his doubt about the truthfulness of images, Richter painted his subjects in greyscale (he is on the record as saying that grey is ‘the epitome of a non-statement’ and ‘only notionally real’). The series begins with a portrait painting of Ulrike Meinhof: it’s followed by two paintings of three members of the group being arrested; three pictures of Ensslin on her way to an ID parade; Ensslin’s body hanged from prison bars; an image of Baader’s cell; a painting of the record player that hid Baader’s gun; two images of Baader shot and bleeding out; and three head-and-shoulders images of Meinhof laid out terminally on her cell floor. A final image, originally cribbed from TV footage, confirms the radicals’ mass appeal – it shows three coffins being carried through a crowd during their multitudinous funeral.

According to critic Gertrud Koch, ‘what characterizes these paintings is their reference to the temporality of our imaginations, the haziness of our memory, its vagueness, the sinking into amnesia, the disappearance and blurring’. But there is also a sense of momentous grief: anguish over the loss of life taken early, but also over the epochal failure of ideology.

As Richter put it in one of the many interviews he gave to counter the false impression that he was glorifying terrorism in October 18, 1977: ‘[My paintings have] to do with the everlasting human dilemma in general: to work for a revolution and fail.’

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview