I was twenty-five in 1968 and living in Rio de Janeiro, very much inspired by Tropicália. I would listen to Caetano Veloso as I painted. On seeing my gouaches, Veloso’s record label asked me to produce the cover for Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis, the album he made with Gilberto Gil and others (though my design was subsequently replaced by a photo of the musicians). Tropicália was a totally new culture, a radical counterpoint to bossa nova – inspired by the sound of the streets, as well as of the jungle.

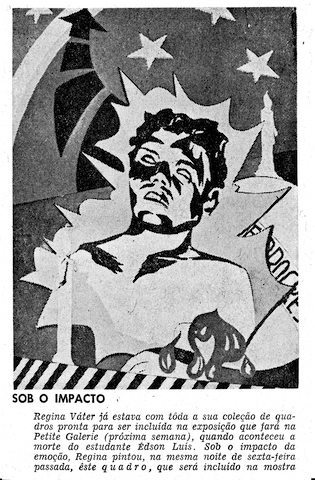

One day in March I heard the news that a student, Edson Luís de Lima Souto, had been killed by police in a cafeteria. I couldn’t sleep that night, and to cope with my insomnia I made a painting of the boy from the pictures in the newspaper. He was shot by police during a sit-in. A friend, the photographer Evandro Teixeira, saw the painting and showed it to Alberto Dines, the editor of Jornal do Brasil. The day after, it was published in the news section of the paper. I joined the ‘Passeata dos Cem Mil’ (‘March of the One Hundred Thousand’), the huge demonstrations sparked by the student’s murder, with Milton Temer, then a journalist but now a politician and activist. We got very close to where Vladimir Palmeira, a student leader and later a politician, spoke to the demonstrators, but what I remember most clearly are the helicopters flying overhead. (It reminds me of the day John Lennon died, when I was in New York: something similar happened as we gathered in Central Park.) It was scary to hear them. At one point Palmeira called for everybody to sit down, and this whole ocean of people sat in silence for a moment.

It was a year later, in 1969, when Emílio Garrastazu Médici came to power, that the dictatorship was at its worst. Under him the repression was really bad. Anyone who was thought to be a communist was killed: they were throwing people into the ocean from aeroplanes. I decided to make an installation on the beach and offer it almost as a prayer to Brazil. Copacabana used to be full of altars to the gods of the sea, made by people following the old African religions. It is so sterilised these days, especially now we have this evangelical bishop as our mayor. So I too built an altar, which featured the figure of the Black Madonna. Brazil protected by a Black Madonna; we are, after all, a dark-skinned country. I surrounded it with everything I could find on the beach, the natural stuff, the garbage, everything.

After that I won a prize and I planned to go to Paris, but a friend of mine told me not to. He said, “Paris has already gone. Go to New York.” I decided to follow his advice. I’m glad I did, because I met Hélio Oiticica there, and he was obviously very important to my life. Leaving Brazil I never thought I would ever live through something like the dictatorship again; I moved back in 2011 and I think the situation now is even more sinister. There is a veil of democracy, but we are in a state of deception. I have two knee replacements, but if I didn’t, I would be out on the streets again.

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview