“Home is where the hatred is,” sang Gil Scott-Heron in his 1971 song of the same name, built out of “white power dreams”. The sentiment runs through Ekaterina Degot’s first edition of this annual interdisciplinary arts festival in Graz, which explores the blood-and-soil constructs of identity underpinning the far-right resurgence. That you need a brass neck to use a state-funded festival to critique the recent trend towards identitarian politics (Austria’s national coalition includes the Freedom Party, founded by former members of the Nazi Party) was made clear by an entertaining speech in which, standing in the bustling Europaplatz and backed by a parping brass band, Degot explained the title’s explicit allusions to National Socialism beside a line of stony-faced politicians.

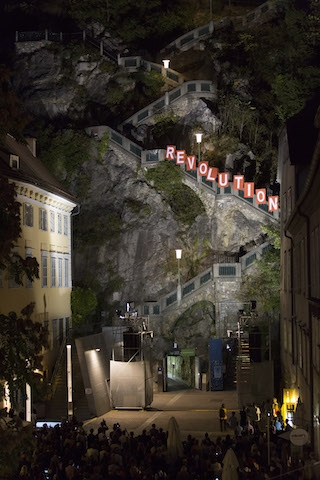

The unification of a supposedly ethnically homogenous Volk was the pretext for the annexation of Austria by Germany, a point hammered home by the first performance of a festival that has historically been rooted in avant-garde and politically engaged performance. The Bread and Puppet Theater led a crowd along the route taken by Hitler during his valedictory tour of the country after the Anschluss, stopping to stage allegorical scenes in support of migrants and those otherwise excluded from society before breaking bread with the audience. The Brechtian approach was shared by Roman Osminkin’s spectacular Putsch (After D.A. Prigov) (2018), in which volunteers carrying signs with letters of the alphabet shuffled up and down a flight of floodlit mountain steps to spell out garbled revolutionary phrases. It concluded with an opera singer making familiar dictatorial gestures as he bellowed out “Es Ist Zeit” (it is time), a phrase beloved of Austria’s thirty-two-year-old prime minister. In both performances the combination of agitprop with vaudeville engages a crowd composed in roughly equal parts of festival devotees and curious bystanders without seeking to alienate parts or sermonise to the whole.

Later on the opening night, amidst the ruins of Graz’s hilltop castle, the aforementioned local dignitaries found themselves sitting through a concert by Laibach of which the same couldn’t be said. After a grandstanding lecture calling out the recently elected Austrian government as fascists, the veteran Slovenian industrial band proceeded to desecrate the soundtrack of The Sound of Music (1965) while a giant screen spliced doctored images from the film with footage of ants clambering over each other. The invitation to Laibach to perform these cover versions was designed to expose, Degot explains in an accompanying publication, how closely the feelgood film’s infusion of the Austrian landscape with mystical power (“the hills are alive”, and so on) resembles the Nazis’ own invocation of a mystical Heimat to which the Volk is bound. That a purportedly antifascist narrative is driven by one of the insidious ‘little fascisms’ that structure national identity is a more complex idea than the bombast of Laibach allows, and indeed subtlety was a frequent victim of the festival’s political commitment. Whether this is a necessary sacrifice in the current political climate, or whether it risks entrenching the divisions in Western society, was foremost among the discussions it prompted.

The relationship between constructs of home and identity was explored with greater nuance at the Kulturzentrum bei den Minoriten in a group show that – alongside other artistic projects installed in local institutions, abandoned bars and, in the case of Tony Chakar and Nadim Mishlawi’s narrative soundpiece Hum (2018), on a hotel rooftop – complements the performances and theatrical events that are the festival’s focus. In kozek horlonski’s 16mm homage to silent cinema Uninvited (2017) a character signs a contract with a Nosferatu-esque character who, in a beautifully realised scene, then enters his bedroom to steal away his reflection. The home is the first and recurring site of trauma, and this silent horror offers the most concise visual expression of Freud’s description of the Unheimlich (normally translated as the uncanny, but literally ‘unhomely’) that haunts the show through doubled, distorted or otherwise twisted representations of the domestic. At Haus der Architektur, East German-born artist Henrike Nauman’s Anschluss ’90 (2018) imagines a scenario in which German unification had extended (once again) to Austria by constructing a creepy showroom out of kitschy furniture dating from the fall of the Berlin Wall. Included among the melting wall clocks and sofa-beds with inbuilt FM radios is a selection of fascist reading material, unsettling the nostalgia and suggesting that the current resurgence of the far right had its seeds in the triumph of capitalist consumerism.

This play on estrangement from one’s own past is taken up in different ways: Christoph Szalay creates a fractured and polyphonic visual poem (Heimat, 2018) by embroidering found texts into strips of fabric through which the reader walks; Michiel Vandevelde’s Human Landscapes – Book I (2018) adapts Turkish poet Nâzim Hikmet’s epic of displacement for a cast who deliver excerpts while tracing a delicate choreography around an audience laid out on the floor of a darkened room. That a supposedly shared past can mean different things to citizens of the present is most eloquently demonstrated by Ekaterina Muromtseva’s short film In This Country (2017), which sets stories about the Soviet Union, written by young children who had no personal experience of it, to shadow play.

The irreverence and creativity of children is, suggests Roee Rosen’s Kafka for Kids (2018), inherently opposed to the logics on which fascism depends. Commissioned as a feature-length film for the 2019 edition of Steirischer Herbst, the work-in-progress is presented in three parts: a musical performance, an excerpt from the unfinished film and a monologue. Reasoning that comedy in Kafka’s novels is not an escape from the realities of life but the most effective expression of their absurdity, the Israeli artist adapts passages from The Metamorphosis (1915) – a horror story in a home infested by vermin – into ditties performed by Igor Krutogolov’s Toy Orchestra using instruments including a Hello Kitty drumkit and squeaky rubber chickens. It’s a reminder that in all great literature, as in life, the comic can never entirely be separated from the tragic, nor the beautiful from the ugly.

Kafka for Kids concludes with a disastrous standup routine by a hyperactive Jewish comedian called Roee Rosen, brilliantly played by Hani Furstenberg to the accompaniment of drumrolls and ill-timed audience prompts to laughter and applause. Disintegrating jokes about 9/11, Jewish doctors and Barack Obama brilliantly deconstruct the form, exposing the simple narratives and inbuilt prejudices on which comedy depends. It is often deeply uncomfortable. “You can’t compare the Israeli occupation with the Holocaust,” the comic berates the audience after it has been instructed to laugh against its own inclinations. “They’re not the same at all… Whatever you think of the Israeli occupation, it is much, much better than the Holocaust.” This astonishing performance delivers the most enduring lesson of the festival: that resistance to the seductive certainties and scapegoating of rightwing populism requires that we embrace contradiction, ambiguity and complexity.

Steirischer Herbst: Volksfronten, Graz, 20 September – 14 October

From the October 2018 issue of ArtReview