Luhring Augustine, New York 29 June – 11 August

KRIWET (Ferdinand Kriwet), a precocious jack of artistic trades, emerged in the postwar German Rhineland during the wildly creative 1960s. He published his first book – a mass of words lacking punctuation – in 1961, when he was nineteen and West Germany had a single national TV station (the second was launched in 1963). He made recordings, broadcasts and films; designed exhibitions; and created visual works printed or stamped on commercial materials like PVC and aluminium. In 1968 he performed with Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention in Essen.

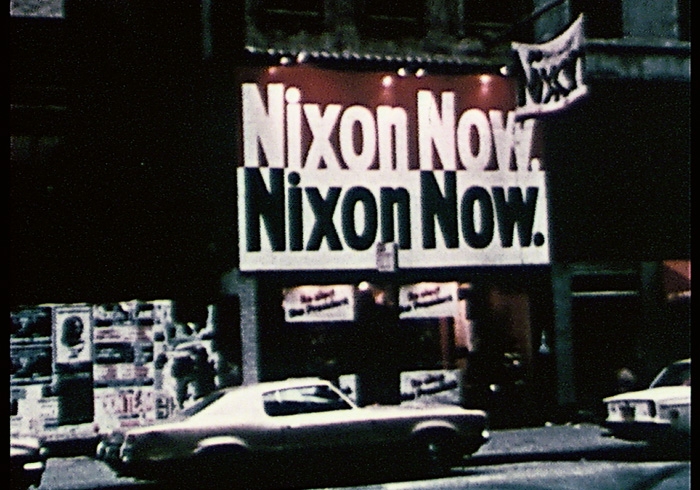

This exhibition offers a fair overview of KRIWET’s work. Two 16mm films, Apollovision (1969/2005) and Campaign (1972–3/2005), montages of news coverage of the Apollo 11 moonlanding and the 1972 US presidential campaign respectively, are screened sequentially on opposing walls. KRIWET filmed them directly off television sets, and each is leavened with ads, football games and other noise from the American mediascape. A grid of Text-Signs (1968), concentric circles of words stamped on commercial aluminium squares, hangs nearby. Several pieces from the series Text Dia (1970), rings of words printed on clear PVC sheets measuring over three-by-three metres, are draped from the ceiling. Together they form an immersion in near logorrhoea.

The vinyl-printed texts appear, at first, to be nonsense, but they coalesce into overlapping words such as ‘gamemeatyumyum…’. The mix in the Text-Signs form more obvious combinations, for example ‘SODOMESTICK SADOMASORRY’. The films, however, are more potent, deftly revealing the mix of commercialisation and entertainment that has increasingly degraded American politics and intellect. Campaign begins with a commentator’s statement that “TV is politics and politics TV”, though given current circumstances one may be forgiven for feeling nostalgic about the hazy black-and-white footage of Richard Nixon. Collages from 2004, deforming and reforming words in patterns that recall concrete poetry, supplement but don’t add much to the earlier works.

In 1970 KRIWET described himself as a ‘personalized word collecting society’, and referred to his work as PubLit or ‘public literature’. It’s best understood as language liberated from its standardised packaging and invading space much as information invades the contemporary landscape – a realisation inflected by Walter Benjamin’s One-Way Street, in which Benjamin describes ‘locust swarms of print, which already eclipse the sun of what city dwellers take for intellect…’, and also part of a decades-long development in how information is understood and refracted in art.

For KRIWET, language has its own sensual quality, and his works provide a key to unravelling the legerdemain practised on content by contemporary media and politicians: through their sensory physicality, his texts encourage a form of active reading that, as Roland Barthes once described it, shifts the onus of creating meaning from ‘author’ to ‘reader’. Doing so remains a potent gesture today, when too many have ceded the responsibility of critical engagement.

From the September 2017 issue of ArtReview