Three heads come together, forced into position by the figure on the right, whose arm stretches out seemingly to strangle the figure on the left. Stranger still, the three heads share only two mouths – frozen rictuses, one a grin, the other a grimace. The central Janus-faced figure stares both ways, his eyes met by the eye of the companion to his left or his right, each of whom presses their face into his. This untitled 2014 work by Christina Forrer, its subjects woven into cotton and linen fibres that are uncoloured but for the pink grasping arm, the heads then filled in with dark purple, blue and brown gouache, is relatively simple and unsophisticated in contrast to the Swiss artist’s larger, vividly coloured tapestries. Nonetheless, the fundamentals of her most recent figurative weaving are there: dramatic interpersonal exchanges, functional or dysfunctional, designed and worked into the very support of the work.

Forrer grew up in Zumikon, outside Zürich, went to study in California at the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, in the early 2000s, and has remained in the US ever since. For a decade or so after her studies she assisted other artists, among them Robert Therrien, keeping her own practice under the radar. We first met in 2008, when she was exhibiting design-inspired drawings of speculative objects at an exhibition by a group of LA-based friends at Zürich’s Bolte Lang gallery, but by her own account, her artistic breakthrough happened after this, when she began to include figures in her work; then the oeuvre coalesced and “made sense” to her. Subsequently learning pattern weaving and tapestry weaving from Babajan Lazar, a Kurdish-American teacher, during the late 2000s, she found tapestry to be a medium that enabled her to work both intuitively and just precisely enough. Critics embraced her fresh imagery when Grice Bench gallery in Los Angeles mounted an exhibition of these works in 2014, a selection of what had, by then, become highly sophisticated tapestries and drawings featuring characters from old and recent folklore, such as Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz or a horseriding warrior with a lance. This past spring, following a further show at Grice Bench, Forrer had a solo presentation of tapestry works alongside a single sculpture and sketchbooks – books made from collages on photocopies of found images and the artist’s drawings – at the Swiss Institute in New York. Its title: Grappling Hold.

It is a perverse family tree of interconnection; like the title, which could be translated as either bound or bonded, it intimates that familial life can mean joy or inescapable horror.

As you would expect, the works in Grappling Hold (the title refers to a wrestling grip) again featured dramatic scenes, though these characters are no longer from fable or legend but everyman and -woman. The show’s focal point was the intensely coloured tapestry Gebunden (2017), more than two metres tall and one and a half wide. It could be a family portrait, with a happily embracing couple at its centre, but each of the two is grasping a smaller infant figure by the neck, starting a chain of similar cruel grips. A further adult pair look on from above with horror, though they are equally involved in grabbing infant limbs or necks. It is a perverse family tree of interconnection; like the title, which could be translated as either bound or bonded, it intimates that familial life can mean joy or inescapable horror. We are products of our ancestors and have been most likely nurtured by that same family. The diagrammatic structure of this piece underlines the inevitability of our inheritance and at the same time illustrates the historical fact of shared genes as a lived experience. This version of events is extreme, yet let’s not forget that cats pick up kittens by the neck when taking care of them.

“I don’t think of the world in terms of large events,” says Forrer when we talk by Skype, LA morning and Zürich evening. Her interest lies, rather, in “what happens on a small scale”; the minor, the family life most of us share, can clearly incorporate drama, whether physical or mental, which appears major and overpowering when we’re in the thick of it. Not all the woven tableaux in the exhibition were domestic, and several scenes illustrated intergenerational tension. Eight (2017), nearly three-metres wide, shows a queue of people heading stage-right. The elderly pair first in line have fixed grins, whereas there’s dismay and revulsion on the faces of those behind, including a woman who tries to shield a scared child. The scene is horrible for its presentation of concurrent glee and fear; it is worrying, or even dreadful, to imagine what unseen stimulus would provoke such extreme responses. What would be welcomed by an older generation but repulse or even terrify younger viewers? An antique toy – featuring two wooden acrobats positioned in such a way that allows a child to swing the figures around and around – borrowed from the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, completed the show at the Swiss Institute. They are bound together in their gymnastics just as Forrer’s figures are ensnared in their relationships. For any social or collaborative being, other people are inevitable, and yes, at times they can be hell.

Forrer presents us with everything at once, an image we can take away and reflect on later, like folk art illustrations that are not made to be contemplated for long

Eight is woven in cotton and wool, Gebunden in cotton, wool and silk, all of them bright, saturated yarns. The clashes and contrasts of colour recall quilting’s aesthetic of reuse, though Forrer also uses heightened colour to weave florid or veiny faces, for instance. A few final telling details were added to both in pen once the pieces had come off the loom, like a snotty nose on the child in Eight and the eyes of the smallest figure in Gebunden. Forrer weaves on a handloom, working from a cartoon she has drawn either digitally or by hand, or using a combination of both, the cartoon then placed behind the developing fabric. While she weaves, the structure of the loom means that only a band of little more than 10cm wide of the work is visible at any given time, so its producer has a blinkered, closeup and incomplete view until the revelation of the finished work. Whether the images are generated horizontally or vertically also radically alters the structure and dynamic of the image for Forrer: Eight has vertical bands, Gebunden horizontal. The results are imperfect, for the weave is thick and the design is translated into the fabric by eye. Forrer’s design generally distils countless ideas into something that the medium’s resolution dictates be simple; in any case, were all her thinking to be visible in each image, it would be “unbearable” says Forrer. She is informed by a broad array of sources, ancient and modern. She cites Hannah Ryggen and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s tapestries, as well as Lise Gujer’s, as important influences, along with many forms of folk, pagan and religious art, and craft and decorative techniques too; in some of her pieces these references are explicit. And the works are fluent in contemporary image production as well: the variations of scale and the abrupt shifts seem to borrow from a filmic or comic-strip language, like the two topmost figures in Gebunden that tower, oversize, above the rest of the family.

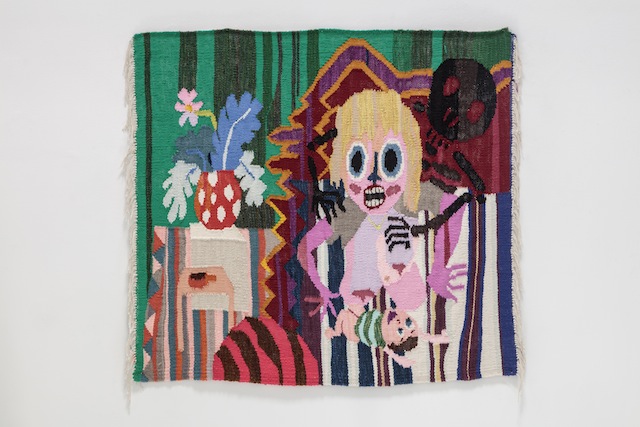

An untitled work from 2016 shows a woman kneeling on a bed with a tiny infant before her. She is petrified: a black skeleton, representing death, hangs over her back, grabbing her by the shoulder and the breast. The baby meanwhile laughs obliviously, and flowers and leaves in a vase on the bedside table appear in rude health. An ambiguous and intolerably troubling scenario is taking place, but is frozen, encapsulated in one image, this immobility underlined by the blunt colour transitions. Forrer presents us with everything – mother, child, spectre, surroundings – at once, an image we can register and reflect on later, like folk art illustrations that are not made to be contemplated for long. Folk artforms and traditional crafts frequently reflect contemporary events – ‘pussy hats’ are an obvious example – and these endeavours can positively refocus our view of particular events. Forrer, in contrast, refines how we look in general by borrowing the appearance of fixed narratives that is native to genres like religious iconography. Her work presents life, local and intimate, real and fantastical, as an absurd fait accompli, arrested in its tracks. Nonetheless, and although she works in a stable and measured medium, her pictures are unruly and unsettled. For ultimately, she cannot allow a fatalistic view. Taking domestic and interpersonal interactions as her subjects, she challenges her viewers to reject the idea of historic inevitability and the passive regard it encourages.

From the Summer 2017 issue of ArtReview