J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship: Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and the Dying – Typhoon Coming On (1840)

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) was master painter of the natural sublime. A pioneer in the study of light, colour and atmosphere, he cultivated a singular capacity to depict dread, danger, awe and terror.

Advanced art has condemned barbarism for centuries.

Here, for example, is a quote from the Boston Evening Transcript, dated March 1877, about one particularly committed painting: ‘Turner’s Slave Ship is a picture of moans and tears and groans and shrieks. Every tint and shade and line throb with death and terror and blood. It is the embodiment of a giant protest, a mighty voice crying out against human oppression.’

For those of you who think that the power of Turner’s nearly abstract canvas simply grew on its audience over decades like a taste for mouldy cheese – think again. When he first saw it at the Royal Academy, John Ruskin, the painting’s first owner, was so impressed with Turner’s antislavery protest that, writing in his 1843 book Modern Painters, he hailed it thusly: ‘If I were reduced to rest Turner’s immortality upon any single work, I should choose this’.

Turner painted The Slave Ship in 1840 as an abolitionist screed, hoping it would catch the attention of Prince Albert when he attended the British Anti-Slavery Conference (after Britain outlawed slavery in 1833, British antislavery activists worked to outlaw the trade worldwide). Instead, it caught the eye of Ruskin and others who spied in the picture’s composition sublimely fearful echoes of one of the most shameful episodes in Great Britain’s history – the real-life tale of the slave ship Zong.

The Zong took off from the coast of Africa in 1781 loaded to the rafters with human cargo. After veering off course and running short of water, its captain and crew threw 133 men, women and children into the Caribbean. Their logic was both wolfish and mercantile: if slaves drowned rather than died of thirst, the slavers could collect insurance on the cargo. When abolitionists tried to bring criminal charges, England’s solicitor general rejected their claims: no ‘human people’ had been jettisoned, he affirmed, ‘the case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard’.

From the memory of this disgraceful episode, Turner depicted a vision of world-girding rage: a scenario in which, according to Ruskin, ‘the fire of the sunset falls along the trough of the sea, dyeing it with an awful but glorious light, the intense and lurid splendor which burns like gold and bathes like blood’. A solitary glance at the painting reveals two things: the spectacle of awesome nature unchained and an atmosphere of terror as inhuman as any attending photographs of the Twin Towers in flames during 9/11.

Originally titled Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On, the picture depicts a three-master being tossed around like a toy boat on a stormy sea. In the picture’s foreground, arms and legs emerge from the water with chains attached – chum to be devoured by waiting sea creatures and toothy beasts. Above the tumultuous proceedings the sun glowers like a giant apparition. Pointed vertically, its rays thrust a dagger of fulgurant light straight into the heart of Turner’s red-brown sea.

Seventy-nine years after Turner painted The Slave Ship, the poet W.B. Yeats provided the perfect poetic analogue for the Englishman’s depiction of nature-worrying human violence: ‘The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere/ The ceremony of innocence is drowned/ The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity’.

Philip Guston’s San Clemente (1975)

After Philip Guston (1913–80) ditched abstract painting in 1971, he embraced a vulgar, raw and comic realism that increasingly sought to respond to the world and his place in it. Often featuring ominous Klansmen-like figures, his paintings and prints tapped into the general cultural malaise that followed the conventional optimism of the 1950s and countercultural utopianism of the 1960s.

Nearly a decade after Richard Nixon won the White House in 1968 with a mere 43 percent of the popular vote, nine years after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Bobby Kennedy, four years after Lieutenant William Calley received a presidential pardon for killing 22 Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai Massacre and three years after the Watergate scandal brought down the nation’s 37th president, Philip Guston confessed his frustration as an abstract painter to Jerry Tallmer from the New York Post: ‘The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue? I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.’

Besides turning from abstraction to figuration in 1971 – setting off an artworld scandal that rivalled the one that broke out when Dylan went electric – Guston penned a suite of ink drawings (plus a single painting) that savaged the man who was formerly considered America’s most detestable president. The drawings were published posthumously (like Goya’s Disasters of War, 1810–20) as Philip Guston’s Poor Richard. The painting crystallised the repugnance and fury Guston felt for a worldhistorical figure who remains beyond redemption.

Like other artists who confront the issues of their time, Guston learned how to paint from outrage. “One could make a list of all the negative things [that compel me to] continue painting,” he declared in a 1982 documentary, “and [it] would include things like boredom, disgust, all the things you’re not supposed to think about. It’s not inspiration… but anger.” Picasso’s 1937 etching cycle Dream and Lie of Franco was a direct precursor; but so was Goya, who channelled both a hatred of superstition and the abuses of Enlightenment reason into prints and paintings that did their share of power-bashing.

Titled San Clemente, after the small California town that served as Nixon’s ‘Western White House’, Guston’s painting portrays ‘Tricky Dick’ as the very picture of rottenness. Made two years after Nixon’s resignation, it conflates two reported facts about the ex-president. The first is an infamous 1971 photo of him strolling a beach in a stiff dark suit; the second, news that he had developed a painful case of phlebitis, a debilitating but non-life-threatening condition that swelled his leg to twice its normal size.

The resulting picture, which is all hot pinks and shameful reds, features a seaside Nixon – with bloodshot eyes, hairy jowls and penislike nose – looking over his shoulder regretfully as he drags his bandaged limb across the sands. Besides having a dick for a face, the man is all diseased leg. His bloated and veiny shank stands in for his malignant state. It bursts the confines of his sock and ratty suit much like his criminal activities poisoned the office of the president of the United States. Consider Guston’s portrait of Nixon’s raging degeneracy a cautionary tale of the ravages of political corruption – then and now.

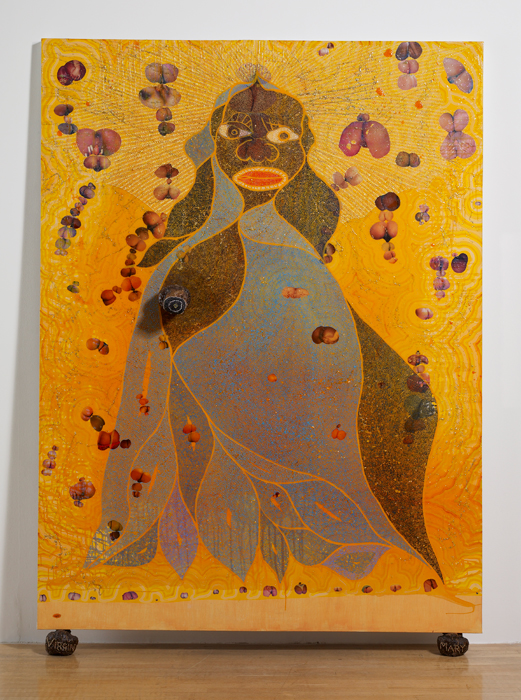

Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1999)

Chris Ofili has weathered success and scandal to become one of the world’s most important painters. His career is proof of the idea that artists are often offered up as canaries in the coalmines of culture. Where his work was once surrounded in controversy in the US, it is now greeted with rapturous praise.

The online Urban Dictionary has two definitions for the verb ‘to giuliani’. The first, deriving from the infamous assault and torture of Haitian immigrant Abner Louima by New York police officers in 1997, is ‘To sodomize with a plunger’. The second, more blandly, reads, ‘To shamelessly take advantage of tragedy for one’s own personal gain’. These riffs on the reputation of the man who served as New York City’s mayor from 1994 to 2001, and who is now President Donald Trump’s attorney, underscore the effect of brazen political manipulation on works of art: like poor Louima, they rarely survive the fracas intact.

In September 1999, Chris Ofili’s elephantdung- decorated The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) – part of the Brooklyn Museum’s controversial Sensation exhibition (after runs at London’s Royal Academy and Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof) – was scapegoated by Rudy Giuliani during his unsuccessful Senate campaign against Hillary Clinton. Serving out his final term, the lame-duck mayor, in cahoots with the conservative Catholic League, called the painting ‘blasphemous’ and ‘sick stuff’ and threatened to pull municipal funding unless it was removed from the show. After mounting legal challenges and tabloid headlines – the New York Daily News called the show ‘B’KLYN GALLERY OF HORRORS’ – the museum’s cause prevailed, albeit at a cost to Ofili as measured in US museum exhibitions.

After a pair of Manhattan gallery shows in 2007 and 2009 and inclusion in a group exhibition at Chicago’s Arts Club in 2010, Ofili made a triumphant return to the US in 2014, with a major retrospective that opened at New York’s New Museum before travelling to Aspen Art Museum, Colorado; it featured new experiments with subject, materials, colour and style alongside several lush Afrocentric Pop paintings from the contentious 1990s. The most important of these, with regards to the history of First Amendment rights in the US, is The Holy Virgin Mary.

Ofili’s Madonna is, in the artist’s words, a ‘hip-hop version’ of the highly sexualised renditions of the Virgin Mary on view in museums throughout the world. Large lipped, wide-nosed and unmistakeably black, she is draped in a blue robe that stands against a gold background. The image is adorned with fluttering putti made from collaged female bottoms cut out of pornographic magazines, while clumps of pachyderm shit make up the Virgin’s right breast (as in Renaissance depictions of the suckling mother of Christ, the robe is parted to expose a single breast) and serve as two pedestals on which the painting rests, to lean back against the wall.

Far from being irreligious, Ofili’s is an update of innumerable other Western virgins, including one that predates Christianity by some 28,000 years: the voluptuous Venus of Willendorf, which was earlier this year deemed pornographic by Facebook’s algorithms. Perhaps in consideration of the Stone Age artist who sculpted the Upper Paleolithic fertility goddess, Ofili turned the body of his twentieth- century Madonna extra earthy with the addition of a few well-placed elephant turds. In case anyone is still shocked, it’s worth recalling Rembrandt’s description of the artist as he who can find rubies and emeralds in the dung heap.

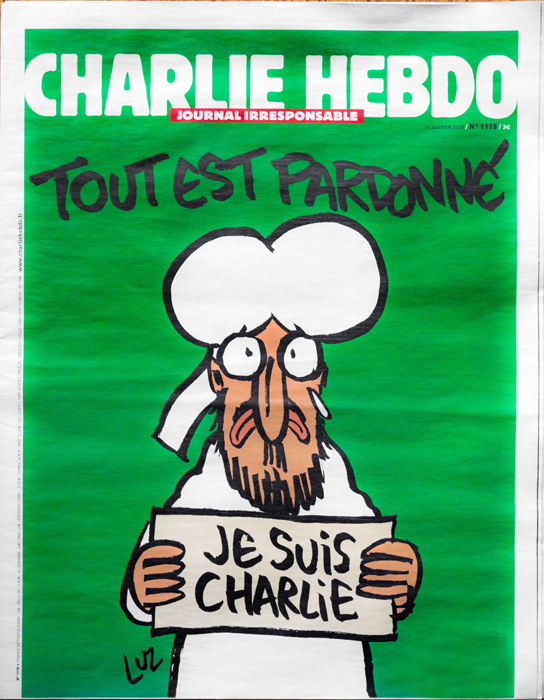

Charlie Hebdo Cover No 1178 (2015)

Charlie Hebdo (founded in 1970) defines itself as secular, sceptical, atheist, far-left-wing, antiracist and also ‘a punch in the face’. It’s ‘survival issue’ sold almost eight million copies.

On the morning of 7 January 2015, two Algerian-French brothers, Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, forced their way into the Parisian offices of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo at gunpoint and killed eight members of the editorial staff, a building maintenance worker, a visitor and two policemen in cold blood. The attack had been in the works for years. Among the publication’s capital offences: it had published a 2011 cartoon cover of the Prophet Muhammad with the caption ‘100 lashes of the whip if you don’t die laughing’.

On the day of the murders, thousands of people took to the streets of Paris to express grief for the victims and support for the equal-opportunity blasphemy that has propelled France’s most serially irreverent magazine for four decades (the journal’s mission statement declares that it is against false idols such as ‘God’, ‘Wall Street’ and ‘two cars and three cell phones’). That message of solidarity quickly spread around the globe via social media. The slogan the crowds quickly turned into chants, placards and T-shirts was the self-subsuming but infinitely hashtaggable Je suis Charlie.

In the days after the massacre, the publication’s skeleton crew of 16 journalists hunkered down in the offices of the French daily Libération on computers provided by the newspaper’s rival, Le Monde. Their purpose: to put together issue No 1178 of Charlie Hebdo, aptly pegged ‘the survival issue’. The edition included 16 pages of new cartoons, previously published articles by two slain journalists and drawings by four of the publication’s fallen artists. Most memorable of all, though, was the anguished, take-no-prisoners cover.

Published on 14 January, the magazine’s cover brazenly sported a cartoon of Muhammad with the French words for ‘Everything is forgiven’ above him. Depicted as a bearded man kitted out in a turban and Islam’s white garments of mourning against a solid green background – the colour of paradise – the figure sheds a tear while looking straight out at the viewer. The roughly drawn prophet is sketched loosely, in the style of Matt Groening or Charles Schulz, a Charlie Hebdo inspiration. Muhammad holds up a sign in his sausage-fingers that reads: ‘Je suis Charlie’.

Besides reclaiming Muhammad from the jihadists, the magazine’s rendering of the comically disconsolate prophet satirises the infantile desire of fundamentalists to murder satire itself, while additionally casting back to an ancient tradition of French social criticism that includes, among other honourable confrontations between freedom and censorship, the tangle between Honoré Daumier and King Louis-Philippe (the artist got six months in jail for depicting the monarch as a gorging Gargantua).

The cover of No 1178 celebrates nothing less than the right to mock, blaspheme and hold nothing sacred. As a caricature, the drawing hilariously sends up death; as an exercise in free speech, it recalls the rousing words of Medgar Evers: ‘You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea’.

The best cartoons straddle the divide between reflection and provocation. Never was this truer than with cover No 1178 of Charlie Hebdo, which was drawn by Renald Luzier, alias Luz, the magazine’s most prominent surviving cartoonist. In the words of one commentator, Luz overslept to draw another day. In doing so, he gifted the world a rare treasure: a work of art that wrings humour from its own tragedy.

Further reading: Christian Viveros-Fauné looks at four iconic moments in art history when artists sought to frame revolutionary ideals

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview