Many cities around the world suffer from a ‘fatberg’ problem, but none other than London has chosen to exhibit one. What does this say about the subterranean nightmares of Londoners? Fatberg! at the Museum of London is the result of the discovery in September 2017 of a clot of wet wipes, grease and human waste, longer in length than Tower Bridge, coiled and sweating beneath Whitechapel Road in the East End. The institution has placed on display their recent acquisition of a piece of this beast, its size limited in order to be able to pass through a manhole. The rest was disposed of, dismantled with pneumatic drills and shovels. Rather than merely operating a prolonged and cautionary public service announcement by Thames Water (though it serves as this too: the utility company has sponsored the exhibition), the museum’s introductory wall text justifies the exhibit via allusions to an apparent public demand to see the freakish offspring of its constant discharge: a demand to satisfy its morbid curiosity for the monstrous.

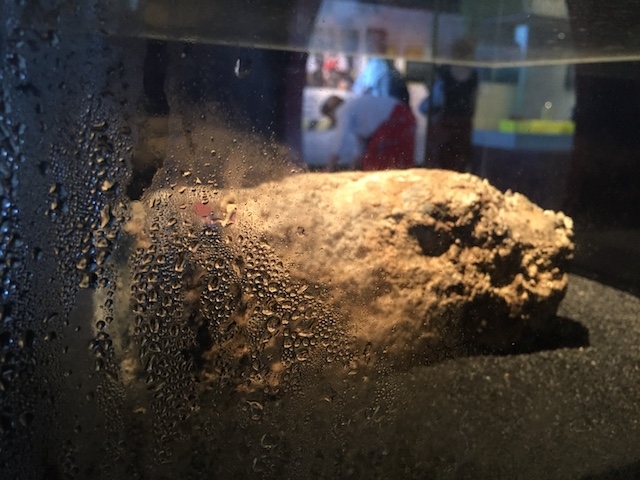

By means of a hazard tape-accented installation of infographics and video interviews with sewer workers, Fatberg! endeavours to distract from the fact that its sole material content is a clot on a plinth. This is a shame, because this lump of urban excreta has a discreet presence all of its own. Sitting on granulated charcoal in a double-skinned glass vitrine, the fatberg is given a delicate, bonsailike aspect. The room is dark and the Whitechapel fragment is lit in raking light like a cuneiform tablet. Pains are taken to emphasise its rocklike texture and ambiguous composition. In this setting it looks like something from Paul Thek’s Technological Reliquaries (1965–66), in which the late American artist presented viscerally naturalistic beeswax replicas of body parts in sleek Plexiglas cases. It also shares some of that series’ material semiotics, such as the prophylactic nature of the glass observation chamber, protecting viewer from object and object from viewer. Though if Thek’s butcher’s-window trompe l’oeil were wax made exquisite flesh, then the fatberg is a brutal rendering of human waste into wax or tallow. Indeed, the bulk of the Whitechapel blockage was in fact recovered and used for biodiesel, and a hundred years ago the berg would have been of great value to candlemakers, on a par with whale spermaceti. In this sense it echoes the long history of London’s subterranean chambers of shit finding extramural value. Long before Joseph Bazalgette’s grand sewer network cleaned up London during the mid-nineteenth century, cesspits were regularly emptied, some of the waste used to fertilise the Home Counties (collected by so-called gong-farmers, who nicknamed the waste ‘night soil’), and in the city a cottage-industry sprang up extracting nitrogen from faeces, to be used in the production of gunpowder. The fatberg however is primarily exhibited as a cultural artefact. Like a farming bygone nailed to the wall of a suburban pub, its use value has moved from the practical to the symbolic.

The subterranean arteries of great cities have at times occupied binary positions in the thoughts of surface-dwellers. On the one hand a soil-dark cloaca, fit only for foul effluent and broken rubbish. On the other they are places of transposition and transubstantiation, of beeline travel, economic opportunity and obscure chthonic worship. The underground of London, particularly, has long held offensive connotations in the public imagination: we have no romantic labyrinths or baroque catacombs for the dead, and even the Roman sewers, which doubtless existed, have turned to dust. Instead we have a fearsome place, full of noxious odours and plague pits – the dead piled multistory like bricks. The notable artefacts to be found under London are often coarse in quality: clumsy iron tools and roughly turned sycamore bowls. And potsherds, the primary typological measure of the city’s strata, are symbolic of a medieval pottery industry that was probably the rudest in Europe, vessels unselfconsciously retaining the marks of the malleable underground mass from which they came.

Three months before the fatberg went on display, Bloomberg Space cut the ribbon on the London Mithraeum, the remains of a third century Roman temple dedicated to the ambiguous bull-slaying god Mithras, situated beneath the company’s European headquarters. Upon its discovery in 1954, the temple’s remains were reassembled nearby on a car park roof, but Bloomberg’s project restores the temple to its original location beside the lost river Walbrook. Many temples to Mithras were deliberately built underground as secret cells, so the restoration of the Mithraeum to a spot that is now located seven metres beneath the buildings of subsequent ages is apt. Bloomberg’s theatrical renovation (touted as the dreaded immersive experience: a tour of this holy site involves both dry ice and a light show) also includes a sleek display of Roman artefacts from the city’s many twentieth-century excavations. Most of these were found in cesspits and rubbish dumps, and like the main aggregate of the fatberg, had been discarded by their original owners.

It is poisonous, almost demonically so. It hatched a scum of flies while conservators were preparing it for exhibition. It gives off gases still and the walls of its case are covered in condensation. It is made of drugs and disease

The material contrariness of the fatberg may be what attracts most. It is poisonous, almost demonically so. It hatched a scum of flies while conservators were preparing it for exhibition. It gives off gases still and the walls of its case are covered in condensation. It is made of drugs and disease. Despite the reams of information about the dangerously putrid composition of the lump, it doesn’t appear very disgusting at all however. Rather, it sits on the knife-edge separating abjection from delicacy. It has the mineral feeling of an old, complex cheese, and reminds me of the benign and ossified white dog shit that peppered the streets of my childhood (a lost relic of the times when bonemeal was an ingredient of most dog food, banned after the ‘mad cow disease’ scandal). It looks cured, not rotten. Sebaceous and crystalline, marine and desert. In fact, ignoring the occasional sprouting pubic hair and bright shard of plastic, the lump could easily be mistaken for a whale product. It looks somewhat like ambergris, the sundried and sea-seasoned sperm-whale bile coveted by perfumers, and the lump’s surprising, phosphoric whiteness dredges up other cetaceous feelings (ghastly whiteness is a common feature of underworld matter: hordes of white crabs and other blind cavern creatures are regularly reported in London’s sewer system). In Moby-Dick (1851), Herman Melville’s albino leviathan is often presented as unholy – as the surfacing of a once-vibrant creature that has strayed too close to the underworld and thereby been drained of sanguine life and thus turned a ghostly shade. Furthermore, in the zoological glossary written to accompany the unabridged version of the book, the older name of the blue whale is given as ‘Sulphur-Bottom’, owing to their yellow-white bellies ‘doubtless got by scraping along the Tartarian tiles in some of [their] profounder divings’.

‘Tartarian and chaotic’ was one nineteenth-century journalist’s description of the new tunnels beneath London. Though we now travel the depths of the city without concern on the London Underground, the original excavations for the Tube regularly produced overwhelming gases and hellish flames, owing to the spontaneous combustion of the vast amounts of methane seeping through the soil. As mentioned, though their discovery is surprising and overwhelming, fumes and rotten waste have always been harvested. Things grown or thrown underground always find some eventual use. Soon after passing the Mithraeum, the buried Walbrook crosses Cloak Lane, where an open sewer once fed into it (‘Cloak’ from ‘cloaca’, the writer Peter Ackroyd notes). This branch of the sewer had its origin further west, at one point running along Carting Lane in Covent Garden. ‘Farting Lane’, as it was once colloquially known, is now the location of the last surviving sewer gas destruction lamp in the country. These were permanently lit Victorian gas lamps that collected sewer methane in a glass dome before burning it for light, with those lining Carting Lane especially nourished by a constant supply of gourmet waste from the patrons of the adjacent Savoy Hotel.

Like the somewhat novel sewer gas lamps, Fatberg! could also be seen as part of the peculiarly British refinement of toilet humour that starts in the playground, continues with Viz magazine and ends in the acquisition of this decade’s sewer waste by a civic museum. The Museum of London presents the lump as both an ossified relic and as something more than contemporary, a mirror that speaks of digestive and geological time, of clots and blockages in circulation, and of the stewarded chemistry of the human body. In the Channel 4 documentary Fatberg Autopsy (2018), analysis of material from a different blockage revealed huge amounts of banned gym supplements including anabolic steroids. The berg also speaks of the imperfect functionality of the city as an extended organism. Rather than flow or float, the fats that make up the fatberg stick to the walls of London’s circulatory system; unable to break down naturally, they require human intervention, and will keep those upstairs busy for years to come. It is a raw material awaiting both physical and metaphorical transformation.

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview