The girls who preen and pose in Rose Wylie’s paintings – with their beachball faces, jointless limbs and childsize feet – seem unaware of their own physical instability. They are, according to the exhibition handout, informed by Wylie’s recollections from the 1970s of her neighbours’ teenage daughter. Painted again and again, in different iterations, ‘she’ is an accumulation of the artist’s memories, misrememberings and external associations: vivid and brash but always about to collapse.

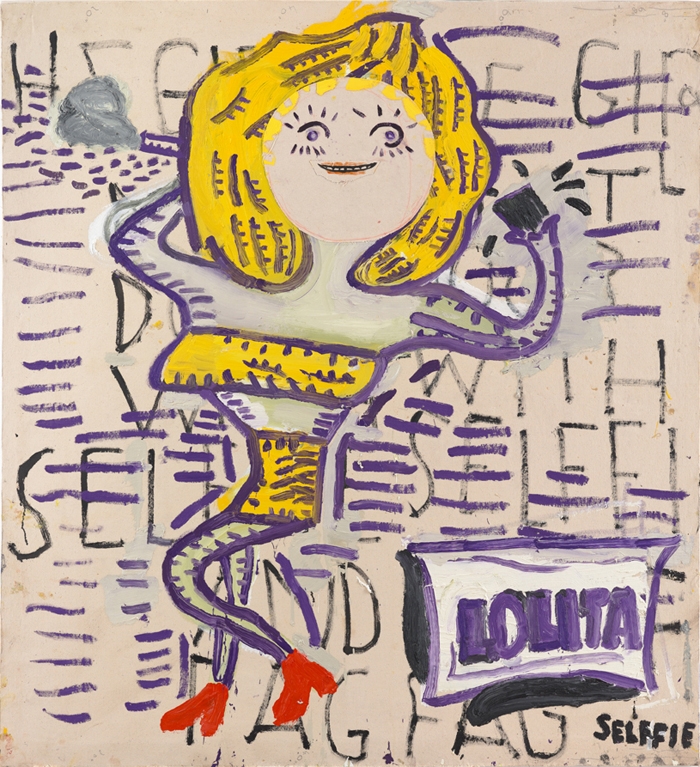

Across the 22 exhibited paintings and works on paper, Wylie’s recurrent colours of cornflower-yellow, lipstick-red, plaster-pink and mud-brown are applied interchangeably to skin, hair, clothing, automobiles and animals. In Lolita and Selffie (2018), a girl with yellow hair – wearing a matching, protruding bandeau top and skirt – poses for a black box held in her hand. Her features are squashed into the top half of her face, which comprises a circular piece of paper stuck onto the canvas so it overlaps her hairline, her skin a light pink against the nauseous green of her neck, stomach and legs. She stands against a background of Wylie’s block-letter scrawl, illegible except for the repetition of ‘SELFFIE’. In the bottom righthand corner of the canvas, ‘LOLITA’ is written boldly in purple, underlined and bordered, like a teenager marking the territory of their diary.

Set out like a storyboard across three canvases, Lolita’s House, Plaster Pink (2018) presents different variations of a scene in which Lolita washes a car parked in the driveway. In each tableau, the girl is naked and small, her back dimples carved out like the sound holes of a violin, while annotations describe the processes and failures of Wylie’s memory. Her reconstructions (con)fuse fact and fiction, as though melted together in the heat of one of the sweltering summer days on which her teenage neighbour earned the name of Vladimir Nabokov’s seductress and victim. Wylie’s paintings collapse her own specific recollections with the symbol of the teenage girl, conflating Lolita’s actions with a more contemporary form of exposure: the selfie, or the constant, virtual representation of the self. Reclining in midair, these girls embody the nascent self-awareness of our adolescent years.

Wylie’s paintings bear the traces of her life in the studio: footprints, pawprints (presumably from a pet), pencil marks, notes, markings and calculations. Yellow Girls, Diary Page (2018) – a small variation of the largescale, nearby painting Yellow Girls (2017) – consists of sketches collaged and drawn onto pages of a date reference guide, listing common and leap years between 1800 and 2050. The pages are overwritten with Wylie’s notations, including references to artist Jimmie Durham, suggested titles for her 2017 Serpentine Galleries exhibition and the email address of a Tate curator. In all their various guises, balancing on pinpoints and staring out of the canvases, Wylie’s young girls embody the expansive possibility and fallibility of memory.

Rose Wylie: Lolita’s House, David Zwirner, London, 20 April – 25 May 2018

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview