‘Contact improvisation is how we survive genocide.’ This phrase from Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s ‘Leave Our Mikes Alone’, and more broadly the entire 2017 essay, is the primary point of exchange between the two authors and filmmaker and visual artist Wu Tsang, as realised in the latter’s solo exhibition at Antenna Space in Shanghai.

In the context of logistical capitalism, or ‘democratic despotism’, as W.E.B. Du Bois coined it in The African Roots of War (1915), Moten and Harney’s essay traces back to the early death of Jamaican dub poet Mikey Smith, through the recent police brutality in the United States and many other names in the ‘undercommons’ histories of black resistance. Tsang’s exhibition is an elegy, or as the artist put it in an interview with Alvin Li, “an enactment”, that dances with the essay by asking how we endure social life in this planetary ‘socio-ecological crisis’.

The show opened with an essay performance, Spooky Distancing II, the first chapter of which was performed at a private salon in a Swiss church in June 2017. The work starts with the voice of the artist narrating a text written in collaboration with Moten and entitled Sudden Rise at a Given Tune, accompanying the mesmerising movements of her long-term collaborator, the performance artist boychild. At the centre of this open installation is We Hold Where Study (2017), a 20-minute, two-channel video projection that takes a choreographic approach to image-making and mourning. The video begins with a voiceover by Moten and slowly evolves into a series of duets via contact improvisation, a technique in which the performers improvise in response to moments of physical touch. Its four chapters – the assembly line; the consultant; the algorithm; the state of war – take their structure from the subtitles of Moten and Harney’s essay.

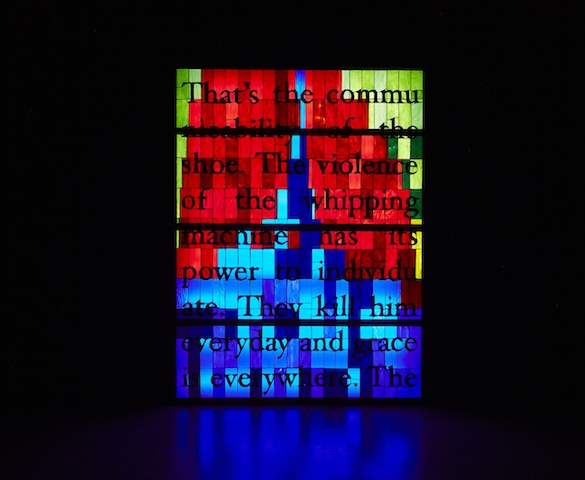

A series of stained glass and lightbox installations are placed around the video projection and are attached to the windows in the back. By taking the medium of stained glass out of churches and mosques, the artist transforms the gallery into a space both divine and radical. Displacing this devotional medium into the secular space of contemporary art and performance connects but also queers it: echoing the title’s ‘sustained glass’. Moten and Harney’s words, incorporated in the video and inscribed onto the open installations, integrate the moving image and the installation. One line stands out, translated into Chinese from the original English text of Leave Our Mikes Alone: ‘they can’t see our hands, and this is demonic to them’.

Perhaps ironically, leftist Chinese intellectuals first voiced support for black resistance in the then-called ‘imperialist capitalist state’ across the Pacific back in the 1950s (and it’s notable that Du Bois met Chinese delegates during the Afro-Asian Writers Conference in Tashkent in 1958). That old campaign might have found support in the space now devoted to Tsang’s show, which was then the warehouse of a workers commune (a history it shares with many creative spaces in China today). A different form of internationalism, if not transcontinental solidarity, has taken over. That is the conundrum that we face today.

Wu Tsang: Sustained Glass at Antenna Space, Shanghai, 23 September – 15 November, 2017

From the Spring 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia