Enrique Cárdenas, the protagonist in Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel, The Neighborhood (2018) is a millionaire. In the 1980s, during the tumultuous years of Alberto Fujimori’s presidency of Peru, Enrique ends up in prison having been charged with murder. As soon as he steps into the murky prison, a figure who can’t be identified in the darkness, forces him to perform a blow job.

“Guard! Guard!” screams the millionaire to no avail.

“You were lucky that I came forward. If those blacks over there get you and take you to their corner, they will pull down your trousers, put a little Vaseline in your asshole, and line up to fuck you for as long as they want. And that wouldn’t be the worst, because at least one of them has AIDS. But don’t worry, as long as I protect you, nobody will touch you. I’m the law here, white boy,” says the mysterious figure.

This is how the Indian prisons too function. The only difference would be that in India if you are rich, you have the luxury of customising the prison according to your convenience. It is expensive, but doable. A similar atmosphere to Llosa’s prison would likely be found in another of India’s merciless places: orphanages that host kids abandoned by their parents.

Rekha grew up in one such an orphanage. When she was fourteen years old, she is adopted by a family in Bangalore. After serving as a maid in their house for about two years, she comes to know that she is stuck with a human trafficking gang that illegally transports women to a brothel in Mumbai. She tries to escape. The gang chases her down and stabs her with a knife. In the resulting altercation, Rekha grabs the knife from her attacker and stabs him in the hollow of his neck. One of the attackers dies and two others are critically injured. Rekha faints in the sea of blood. Passersby inform the police. The police arrive and look at Rekha lying in a pool of blood. They conclude that she is dead and send her body to the morgue. A medical examiner there discovers that she is still alive and rescues her.

Rekha pleads guilty to the murder. She must have been seventeen years old then. But since she grew up in an orphanage, she does not have a birth certificate to prove her age. Based on the results of bone-age test, the court ascertains that she must be eighteen years old. She is tried in court as an adult and sentenced to life imprisonment. It is in prison that Rekha meets Anburaj during a drama rehearsal.

Who is Anburaj? He was a member of ‘Sandalwood’ Veerappan’s (1952– 2004) gang. Veerappan was a dacoit, who was active for nearly 30 years kidnapping, murdering and ivory and sandalwood smuggling in the forests of the southern Indian states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. In 2004, he was caught by the police. Anburaj is arrested for kidnapping forest officers and is sentenced to life imprisonment in 1997. He marries Rekha in the prison itself. Anburaj is a school dropout having studied only up to 7th grade. When he walks out of prison in 2016 after his sentence is commuted (because of good behavior and India’s 70th anniversary celebrations) he had turned 36.

Anburaj cites atrocities committed by the police who came in search of Veerappan as his reason to join the latter’s gang. Even though he was with Veerappan, Anburaj says that he did not approve of all his actions. For instance, in one of Veerappan’s operations, Anburaj comes to know only the next day that a ten-year-old boy was murdered. He gets upset and neither of them talk to each other for a few days. Anburaj states that Veerappan would have murdered at least 70 people during his time in the forests. But when asked if he thought Veerappan was a good man, he says “When you consider our society’s current moral standards on one hand and compare him with the policeman on the other, I can conveniently say that Veerappan was a good man.”

Anburaj describes how criminal investigations and inquiries are conducted in prison.

“As soon as I got arrested, along with three other people, I was taken into police custody for an inquiry after a petition with the court. There is a torture cell in Madheswaran Malai called ‘The Workshop’, which is under the control of Special Task Force. I was taken to ‘The Workshop’. I was held in the same room and in the same circumstances as a few other men and women who were kept naked for more than 15 days. They tied the prisoners upside down; their finger and toenails were torn out by pliers. The police officers forced the prisoners to have sex in front of 20 other people even subjecting a father to do it with his daughter, a sister with her brother and a mother with her son. The prisoners were tortured by passing an electric current through wires that were tied to their hands, legs and genitals. They gradually increased the intensity of the electric current. I was subjected to such tortures too. Unable to bear its intensity, my body and limbs would twist in the opposite direction. It would take hours for my body to came back to normal. They would just give us water. We all had to urinate and shit in the same room. Even today, you can notice two circular scars on the back of my heel. Those were mementos from ‘The Workshop’.”

When Anburaj was asked if he thought that his sentence was not justified, he said: “I don’t think like that. I was convicted of kidnapping. But I feel that the length of imprisonment was too long.”

On the subject of his co-inmates Anburaj had the following to say.

“When I was in Salem prison, I met Chako, a prisoner from Kerala. He was convicted for molesting children and murdering them by slamming them against a wall. But he had no guilt about his actions. In fact, he argued his case quite remarkably by himself in the court and never needed a lawyer. Chako was sure that he would be sentenced in both Salem Court and High Court, but would get acquitted in Supreme Court. There was a casualness to his attitude. Events turned out exactly the way he had predicted.

“Similarly there was a mentally challenged prisoner, by the name of Venkatesh. Sometimes the officials would keep me in custody along with mentally challenged prisoners. Those prisoners would be given anti-depressants and kept sedated for several hours in a day. The prisoners peed and shat right where they slept. The room smelled really bad all the time. It was there that I met Venkatesh. He was very affectionate towards me. He force fed me with his share of morning breakfast too. One day, an officer had bashed me in front of him. The next day he waited with a bowl filled with his faeces mixed with water. When the officer came for his rounds, he threw the contents of the bowl right on his face.

“On cold days, the sunlight entered our room through a window warmed a particular spot in our room in the shape of a triangle. We took turns in three’s and would stand in that spot to warm up our bodies. Venkatesh didn’t turn up that day. When I went to check on him, he was seated in a corner with his head bent in between his legs and hands over his head. When I tried to wake him up, he just fell on the floor. He had passed away the previous night itself; the ants had eaten up his eyes completely by morning. The empty eye sockets were filled with blood and water. I can’t forget that friendship even today. His death had shaken me beyond words.”

When asked if he still had faith in the present day government and justice system, he said: “Had I possessed ten lakh rupees, I doubt if I would have had to suffer such a long term of imprisonment. I don’t have any big faith in the present government. Even after the recommendations of the Sadashiva Commission – even after the High Court judgment, compensation has not been disbursed to the ones that were affected in the search operations. None of the guilty police officers have been punished yet. Even in some cases where compensation was awarded, the officers who raped the women in the first place, were themselves sent to hand over the money to them. There are instances where the women refused to take the compensation from the hands of those guilty officers.”

Anburaj quotes another incident to show how the judiciary functions in India.

“When I was handed a copy of the charge sheet by the Kollegal Court, I requested a copy in Tamil so that I could read and understand it. The judge said that it was impossible to give a copy in Tamil. When I said that I must know the reason for charging me, a female magistrate in the courtroom threw a paperweight at me simply because I was Veerappan’s accomplice. I moved aside to avoid it and the paperweight hit the Asst. Commissioner.”

You may know Mohamed Choukri (1935 –2003), who was regarded as the Jean Genet of Morocco for his internationally acclaimed autobiography, For Bread Alone (1973). From being a pickpocket who ended up in prison he transformed himself into a writer. Choukri began learning Arabic, his mother tongue, at the age of twenty, even as he was prison. He started reading Arabic literature and one day he was able to record his own experiences. Similarly, by the time he was released from prison, Anburaj was transformed from an ordinary prisoner to a trained actor, theater director and playwright. He says that the reason for his transformation was Kannada drama, and world literature that he had begun reading inside the prison.

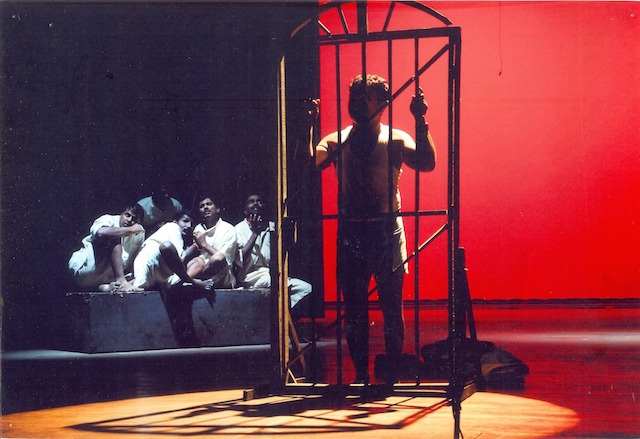

When asked if art had the capability to transform an individual, he said: “I have transformed. Art has the capability to transform anyone. While I was in Mysore prison, there was a prisoner by name Ganesh Nayak there. He was about 25 years old. He said that when he got released from the prison, he would get out, avenge his enemies and did not care about returning to the prison. He was given a character from Shakespeare’s Macbeth to perform in a play. At the end of the play, Lady Macbeth would cry out loud that no matter how she washed her hands, she couldn’t get the blood of her hands. Guilty of her actions, she delivers a long speech in repentance. Watching that scene, right there on stage, Ganesh vouched that he would let go of his vengeance. He is now leading a normal life after his release.”

I am yet to meet Anburaj. When I do, I am planning to request his permission to understand his experiences and write a novel. I had the chance to read Anburaj’s interview in my friend, Jeyamohan’s blog. I am indebted to Jeyamohan for permitting me to utilize Anburaj’s interview for this article.

Translated from the Tamil by Srividhya Subash

From the Spring 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia