Despite the general reflexivity of many popular styles of critique, the implications and intonations of whiteness remain too rarely confronted in contemporary art, not least by white people. Puzzlement and indignation met the assertions, made by many black artists, that the painting Open Casket (2016) – by white artist Dana Schutz, depicting the body of murdered black teenager Emmett Till – was racist, and should be removed from the 2017 Whitney Biennial, let alone, as Hannah Black’s widely circulated letter recommended, that it should be destroyed. Free speech, a universal human right, was affirmed in defence of the painting’s existence, yet artistic freedom was troublingly equated with the inviolability of the museumised commodity, and the voices protesting at the Whitney and on social media, who questioned the capitalist erotics of cultural relativism and appropriation, and underlined the ‘conceptual impossibility’, in Aria Dean’s words, of nonblack identification with the work’s subject matter, were refuted. In short, antagonism was blanketed by a ‘white victim’ response, forestalling conversations about institutionalised antiblackness, the carceral continuum, whiteness’s foundations as a legal fiction and technology of settler colonialism or other social issues framing the painting’s production.

Aruna D’Souza’s new book contextualises this controversy and its response, examining the ways in which the artworld’s liberal racism is not just repetitive, but cyclical. In reverse chronology it recalls two earlier New York exhibitions that were protested for antiblackness: white artist Donald Newman’s 1979 presentation at Artists Space, shamelessly titled The N***** Drawings, and the Metropolitan Museum’s 1969 Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, which included no black artists. Notably, as per the Schutz storm, white commentators shirked complicity: Douglas Crimp, Craig Owens and Roberta Smith, among others, defended an ethos of ‘artistic freedom above all’ at Artists Space. Allon Schoener, curator of Harlem on My Mind, alleged to understand the importance of black artists exhibiting at the Met, but shrugged that ‘I didn’t see that as my responsibility’. The book’s neologistic title refers not simply to the racialised access barriers that define participation in contemporary art but, crucially, to the white-washing of discussions on race in the artworld, whereby actors gymnastically redefine the terms of the debate, conveniently disentangling themselves. The horizon of transformative change is rendered crudely fluid, while art history repeats itself.

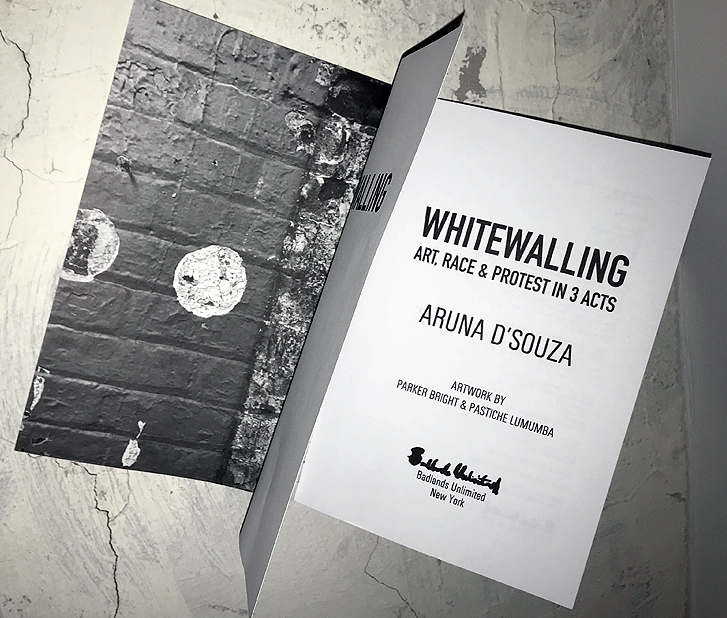

Whitewalling breaks from this, constituting a study of allyship – the difficult process of unlearning, reevaluating and forfeiting privilege in order to challenge structural oppression – through annotation and archival fidelity. The book emerged from its author’s participation in the social-media discussions that generated much analysis of Schutz’s painting. Dispersed, and quickly buried by the accumulative logic of the medium, these remain the property of the platforms on which they were published, yet are critical groundwork for any dissenting student of aesthetics. Social media dramatically outpaces, and outpunches, older formats thanks to its deviance from editorial and grammatical conventions, yet is vulnerable to genealogical link rot. Through compendial citation, and with her polyphonic analysis bolstered by artworks by Parker Bright and Pastiche Lumumba, two important participants in the protests, D’Souza has gathered kindling for future fires.

As D’Souza affirms, there is no neutrality regarding racism. Yet too little writing on art takes up, and complicates, antiracist work – Badlands Unlimited’s Paul Chan claims Whitewalling is the sole book on art and race published this trade season in the US. Demanding historical accountability while celebrating the pathbreaking direct action of groups like the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition and artists including Benny Andrews, Janet Henry and Howardena Pindell, Whitewalling sets a generative precedent. Yet, though progressive, and knifelike in its critical revisionism, the book is about the failure of effective solidarity. The Whitney protests didn’t just demand the removal of a painting from a museum, but the suspension of conditions that precede the painting – and, by extension, the book, this review and my writing of it. Criticism and allyship are finite modes. A more prefigurative politics is clamoured for, one that disassembles the stage while reappraising the acts.

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia