Mr Chan (2018) pretends not to see me, while appearing to see right through me. Staring me straight between the brows, Lai Lon Hin’s photographic portrait of a lifesize cardboard cutout, issued by the Hong Kong government as part of a recent campaign against smoking, is authoritative and uncanny. Hin’s second solo exhibition at Blindspot Gallery is a clear departure from his first, held in 2010, which showed images of Hong Kong architecture saturated with colour and taken with an SLR. Taken on a less conspicuous cameraphone (an iPhone or, in a few cases, an older LG model), without any filter and only the occasional post-production crop, many of the photographs in Gritty Eye capture their subjects unawares, zooming in on the moments when a stranger makes a private face in the public realm.

In Cantonese, the exhibition title translates to ‘sty’ – that painful little lump that can form on your eyelid’s frill, a little pink, a little like a zit. It also describes the proverbial pinprick to one’s eye when viewing something off-putting. The 36 works in this exhibition are primarily arranged in miniseries. For example, Fingers Grazing (2017) is paired with Preparations Before Travel (2018). The first shows two hands grazing the tops of plastic flowers implanted along the moving walkway connecting the Central and Hong Kong subway stations; the second is a found image showing Filipina domestic workers in training. The affinity between this duo lies in the sensation of another kind of real, made possible by an aesthetic that lays bare its artificial construction to capture the condition of the object.

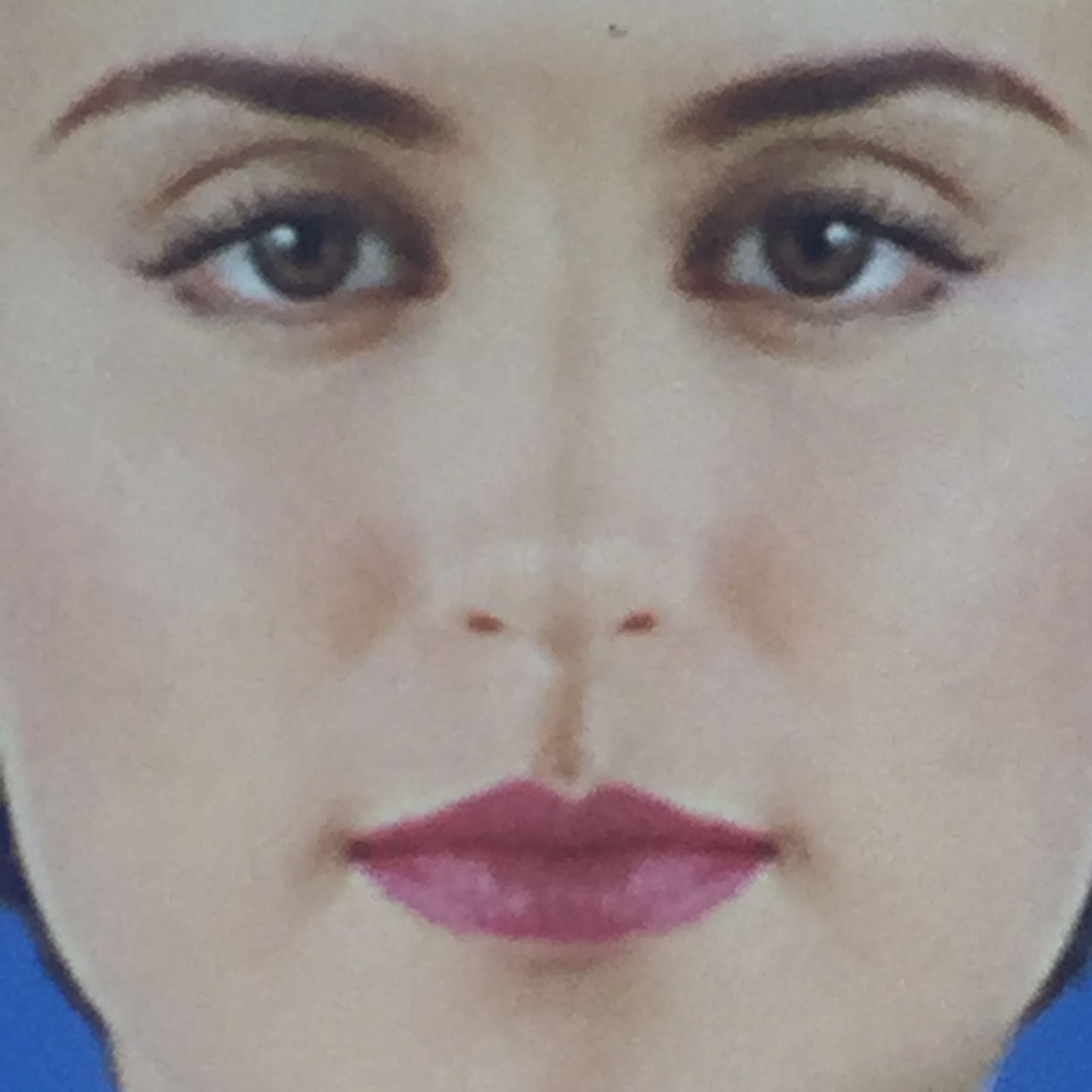

Many of the works in the exhibition have a doubling effect. Airy Bangs (2018) shows two women wearing red lipstick with eyes half-closed; Backed by Brilliance (2018) is a portrait of person standing in front of a lightbox shown in the gallery as an image on a lightbox; an image of two hands almost clasped together has been printed onto a flat sheet curtain that splits down the middle to allow entry into the final chamber of the show. Linda (2018) is presented as a screensaver program: the woman’s face adorning a passport-photo booth in Guangzhou is shown in closeup, and boings from one edge of the screen to another. Usually soothing, this particular screensaver was made discomfiting by the perfect symmetry of Linda’s face, which is made up of half a face mirrored down the middle. The truth-value derived from looking does not always increase with more context, and Hin’s works are focused on the condition of the moment. In today’s media environment, in which everyone produces images at all times, Hin’s work is less concerned with voyeurism than with capturing people and things off-guard.