I Believe My Works Are Still Valid Spike Island, Bristol, 30 September – 17 December

Utopia Korean Cultural Centre, London, 26 September – 4 November

Walking into Spike Island, for the opening of one of Kim Yong-Ik’s two shows in the UK, is an unnerving experience. I scratch my head perplexedly: have I arrived too early or much too late? Are Kim’s artworks still to be unpacked or are they in the process of being shipped away again? Cardboard boxes lie neatly stacked in the middle of the gallery’s floor; artworks dangle from the ceiling, encased in wooden cartons; vast paintings neatly packaged in plastic bubble-wrap lean against the wall, alongside pencilled scribbles that look like the artist’s instructions. Since they are in Korean (a language I do not read), I surmise that they are notes to the curators. Instructions, I guess, that have yet to be followed in this in-transit display. I am wrong. Kim’s show is completely ready to be viewed – or as ready as one of Korea’s foremost artists, activists and teachers is ever likely to be. Kim’s artwork is not about achieving aesthetic full stops; it is never finished; and hence it has never quite begun.

Unlike Kim himself, though, it is important for a review to start at the ‘beginning’ before it reaches the end (however inconclusively circular this finale maybe). My own aesthetic adventure into the mind of Kim Yong-Ik began with the inauguration of Kim’s two major solos in the UK. I Believe My Works Are Still Valid is a retrospective that overruns the warehouselike spaces of Bristol’s Spike Island; meanwhile, in London, the Korean Cultural Centre UK is exhibiting Utopia. Both shows marked the 1947-born, Seoul- based artist’s British debut. While Spike Island presents the seminal moments in Kim’s 40-year career, containing artworks from the 1970s onwards, KCCUK houses a site-specific installation, which uses the gallery itself as a canvas. Both exhibitions, baffling and bewitching in turns, keep curators and critics on their toes.

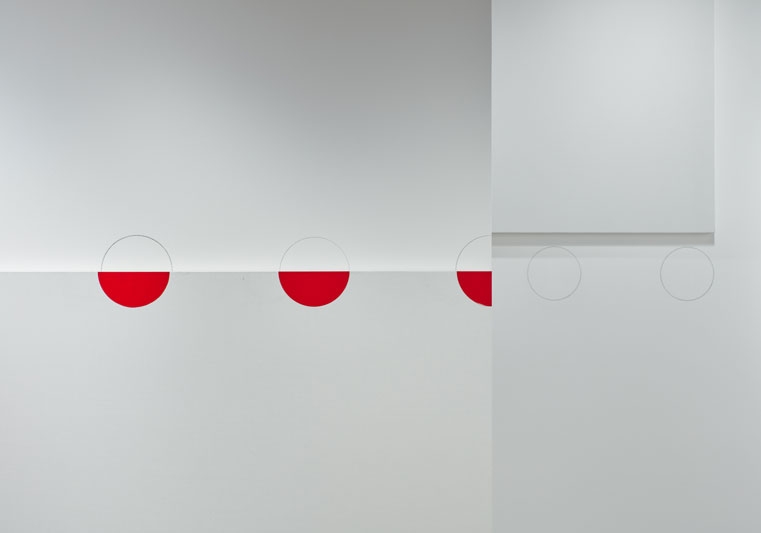

Kim graduated with an MFA in painting from Hongik University in 1980, where he was taught by Park Seo-Bo, a master of Dansaekhwa (monochrome) painting, which dominated South Korean art from the mid-70s onwards. Associated with subtly layered textures and geometric abstraction, Dansaekhwa artworks are thought to signpost Korea’s coming of age; its entry into the story of Western Modernism. After all, Korean monochrome painting visually resonates with American Minimalism from the 1960s – they are both preoccupied with sparsely hued, gridded forms. However, unlike American Minimalism, Dansaekhwa often expands the idea of painting itself. Kim’s debt to Dansaekhwa is visually evident in his two solos. For instance, strong-coloured polka dots – red, blue, green – achieve gridlike formations on the canvases at Spike Island. At KCCUK’s Utopia, polka dots migrate from canvases onto the walls – some- times morphing from vibrant, painted spots of colour to barely perceptible pencilled wall- drawings. Since Utopia’s numerous canvases all count as one work, Kim’s travelling dots appear to convert the barrier between painting and architecture into a moving target. A classic Dansaekhwa tactic or an unconventional hoax?

the tightrope Kim walks between working and joking is a permanent feature of his purposefully impermanent art

For, if the investigation of utopia is usually considered a straightforwardly modernist preoccupation, there is nothing clear-cut about Kim’s relationship to Korean Modernism, which is singularly tempestuous. In 1981 Kim was invited by an admiring Park to exhibit his Dansaekhwa-inspired unstretched canvases at the Young Artists Biennial. He took up the challenge. Upon arriving at the exhibition venue, however, he was reluctant to unpack his work, displaying a pile of stacked cardboard boxes in their stead. He called this new work his ‘Duchampian manoeuvre’. Some critics interpreted Kim’s gesture as a protest against Korea’s military dictatorship of the 1980s; as Kim’s rebuttal of the ‘art for art’s sake’ doctrine of Modernism. Yet Kim’s critique could hardly be classified as wholly antimodernist: Duchamp is the father of Western Modernism, is he not? Where does Kim’s art end and his social commentary begin? Thus, if Kim’s ‘manoeuvre’ angered Park – who never invited him to show his works again – it also foxed Korea’s Minjung art movement, a populist aesthetic that staged its protest against the brutal rule of General Chun Doo-hwan via figurative paintings and prints glorifying nature and the labouring body. The impossibility of ‘placing’ Kim neatly within either of the Korean artworld’s governing dialogues led to his sidelining: from 1991 to 2012, Kim was professor of painting at Kyungwon University, celebrated for his teaching – not his artworks. If that seems poised to change, the tightrope Kim walks between working and joking is a permanent feature of his purposefully impermanent art.

“He kept telling me that things should not be too perfect,” she says ruefully

At KCCUK, curator Je Yun Moon relates that Kim was quite happy to manhandle his paintings with charcoal-stained fingers. “He kept telling me that things should not be too perfect,” she says ruefully. The last room we enter in Utopia has tiny turquoise stars nestled within Kim’s signature polka-dot motifs. Little spots of colour, they seem to glow like a vision of celestial completion. Then again, as we get closer we notice the little stars are stickers: the irreverent viewer can just as easily remove them. And who has the right to halt such vandalism, given Kim’s devil-may-care attitude? “Kim’s unorthodox relationship to his own artworks allows him to ask questions that ultimately disturb the ground on which his practice is based,” reveals Moon. Hence, Utopia’s brochure tells us that the culmination of Kim’s aesthetic endeavour is… the blank canvas. The end is in the beginning; the commencement predicts the conclusion. If that is not a tautology worthy of high art and (yes – let us admit it) low humour, what is?

From the Winter 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia