Catastrophe and the Power of Art offers a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit in these bewildering, vertiginous times. Addressing events ranging from 9/11 and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster to the global financial crisis, the exhibition serves up a series of provocations and dilemmas about what it means for art – and the visitors to this exhibition – to bear witness to disaster.

So it makes sense for the exhibition to open with a section titled ‘How Does Art Depict Disaster?’ Using his signature palette of cardboard, aluminium foil and packing tape, Thomas Hirschhorn has hewn Collapse (2014), an architectural installation representing the ruined interior of a disintegrating building. Within the debris are buried quotes from the writings of Gilles Deleuze and Georges Bataille, the collision of abstract theories of deconstruction and its real-world expression typical of Hirschhorn’s mode of inquiry, and setting the tone for the show.

Immersive installations are presented as offering one means of recreating the emotional and intellectual experience of disaster. Among the most powerful is Miroslaw Balka’s Soap Corridor (1993/2018), a black metal structure through which visitors can walk. Its interior walls are lined with soap, a reference to the practice by guards in Nazi concentration camps of handing soap to prisoners as they entered gas chambers in order to prolong the deception that they were showers. Balancing this horrendous image with the material’s association with cleansing and restoring, the hallway offers a powerful memorial to historical trauma.

That history exists so that we can apply its lessons to the present informs Wolfgang Staehle’s framed toy puzzles of postdisaster scenes (Untitled (09–11–2001), 2001) and Japanese-born Hirakawa Kota’s painted portraits of Fukushima plant workers (Black colour timer, 2016–17). Yet these works jar against the inclusion of Gillian Wearing’s Signs that Say What You Want Them To Sayand Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say (1992–93). For all the delicately drawn irony of these confessional photographs, and their depiction of peoples’ public/private lives, their presence here prompts the question ‘how does Gillian Wearing depict disaster?’

Takeda Shimpei’s mesmerising photographs are altogether more directly engaged with the subject. His Trace (2011) series are suffused with narrative inventiveness, subtle brilliance and psychological depth. In the works exhibited here, the artist provides an intimate and nuanced examination of the Fukushima Daiichi accident by laying contaminated soil samples collected from nearby sites onto photographic film. They leave radioactive residues that read as inky and disconcerting star-speckled skies, conjuring the emptiness and unease of a nation that continues to grapple with the traumas of nuclear disaster.

The possibility of rebuilding after catastrophe is the theme of the exhibition’s second half, presented under the heading ‘Creation from Destruction – The Power of Art’. Among the collective responses are HYGO AID ‘95 by Art, a fundraising initiative in which 25 artists responded to the 1995 Kobe earthquake with artworks and paintings that then toured 60 fee-paying exhibition spaces in Japan, the proceeds from which went towards aid and reconstruction. This extends to the work of Japanese-born architect Shigeru Ban, who is best known for constructing emergency shelters made from cardboard. Scale Model of Transitional Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand (2011) offers a refreshing example of how radical experiment in contemporary art, architecture and design can yield practical results. The exhibition would have benefited from more such examples.

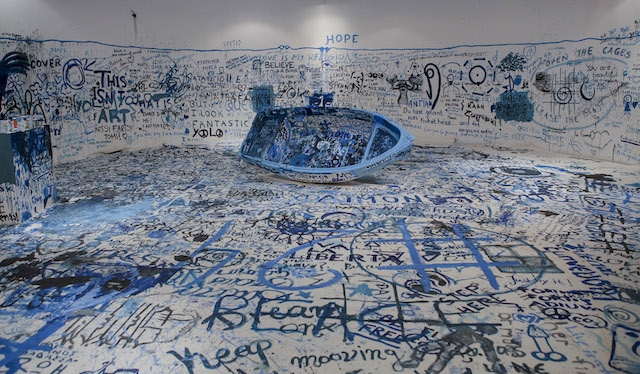

Elsewhere, Japanese-born Hikaru Fuji’s The Primary Fact (2018), a three-channel video installation, combines fact with fiction in an analysis of an ancient burial site containing the remains of 80 young men that was discovered near Athens in 2016. The video splices expert interviews with choreographed actors in a film that gives light and shade to historical records. Yoko Ono’s startlingly timely mixed-media installation Add Color Painting (Refugee Boat) (1960/2016) presents a desolate and abandoned rowing boat adrift on a sea of words painted in blue onto the walls and floor, among which stands out the phrase ‘THIS ISN’T ART’. Koki Tanaka’s Provisional Studies: Action #8 Rewriting a Song for Zwentendorf (2017) and Tatsuo Miyajima’s Sea of Time – TOHOKU (2017 Ishinomaki) (2017), meanwhile, offer reminders that the best means of avoiding future catastrophes is to cherish and respect our relationship to other people, species and lifeforms.

Comprising 40 artists and collectives, this sprawling exhibition occasionally feels bloated and is guilty of overreaching in its determination to shoehorn in ideas, geographies and aesthetics related to the broad theme of disaster. Yet numerous of its works hint at mankind’s resolute ability to mend, reconstruct and rebuild in the face of adversity. In the current context, that alone is worth the price of admission.

Catastrophe and the Power of Art at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 6 October – 20 January 2019

From the Winter 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia