Once the preserve of freaks, collecting is becoming ‘the norm’ – and thus going out of fashion

The first case study introduced in James Delbourgo’s deep dive into the subject of collectors and why they do it is ‘a thoroughly modern manic’. So modern in fact that he’s not even real: the taxidermist Norman Bates, obsessive accumulator of stuffed birds, serial killer of women, all-round momma’s boy and ‘star’ of Alfred Hitchcock’s most famous movie, Psycho (1960). In his thoroughly modern study, Delbourgo, a historian of science, collecting and museums, will seamlessly switch between collectors real and imagined to explore the link between accumulation and danger that Bates embodies – that ‘underneath their veneer of reason and civility, collectors are febrile, volatile, and warped’. It’s a notion, Delbourgo, informs us, that dates back to premodern times. It’s also one, he will later conclude, that’s going out of fashion. Because collecting has become boring. Having been the preserve of freaks, it’s becoming ‘the norm’.

Perhaps the last is why Delbourgo keeps reaching for characters from the fiction section of his bookshelf: to Jean des Esseintes (star of J.K. Huysmans’s novel A Rebours, 1884), who bejewels the carapace of his pet tortoise to the extent that it can’t move and expires; or Oscar Wilde’s ageless, murderous libertine Dorian Gray (1890); Bret Easton Ellis’s soulless consumer and killer Patrick Bateman (American Psycho, 1991); Orhan Pamuk’s obsessive romantic Kemal Bey (The Museum of Innocence, 2008), collector of his dead lover’s used cigarette butts and anything else she touched while alive; and, slightly more obscure, Arto Paasilinna’s Volomari Volotinen, owner of Christ’s clavicle and the world’s oldest pubic hair (Volomari Volotinen’s First Wife and Assorted Other Old Items, 1994). But you can’t help feeling that the underlying message of Delbourgo’s obsession with the imaginary is that whatever it is that defines a collector is about perception more than actions. Or that this book is proof of the extent to which the real and the imagined have blurred. Yet elsewhere Delbourgo just as effortlessly draws on real-life examples that are no less strange than fiction.

For Delbourgo, collecting is a product of a premodern world in which art and science were not separate domains. Its origins lie in attempts to know the world, and in doing so to locate oneself. So Hans Sloane, whose collection became the foundation of the British Museum sits alongside Alfred Russel Wallace who took a gun (well, several) to the wildlife of Southeast Asia in order to furnish natural history museums back in Britain with curiosities and wonders. He was, Delbourgo suggests, to wildlife what Norman Bates would be to young women. The author traces the origins of the pathological study of collecting to Ming dynasty China, where obsessive collectors were said to be suffering from an excess of pǐ. Pǐ was characterised as a mental obsession that could lead to physical blockage (the formation of a pǐ stone) according to one sixteenth-century Chinese medical text. But, curiously, having an excess of pǐ was at once something to be proud of – a testament to refined sensibility – and an affliction. As Delbourgo moves across centuries and continents he uncovers how the understanding of collecting has oscillated between these two poles; how the underlying causes of collecting have shimmied between the psychological and the physiological.

For Sigmund Freud, Walter Scott and Honoré de Balzac, writing from the late eighteenth century through to the early twentieth, collecting was a substitute for sex and collectors were generally ‘loveable bachelor losers’ who couldn’t get any. Back in the seventeenth century, on the other hand, in the case of Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated rather than marry and was rumoured to have lovers of both sexes, collecting was seen as a sign of her moral and sexual excess. Whichever way you thought about collecting and sex, for Freud, as Delbourgo has it, the erotics were both universal and entirely anal: ‘we all begin life as collectors – of our own feces.’ (Delbourgo cites a 1908 essay, ‘Character and Anal Erotism’, in which Freud suggests that children discover power, more particularly power over their parents by retaining excrement.) The Austrian’s associate, Karl Abraham, however, took things a step further arguing that collecting was a manifestation of a cannibal instinct driven by an aim ‘to incorporate the object in’ themselves (which links to the hero of Pamuk’s novel, who likes to put his lover’s things in his mouth).

Some neuroscientists today suggest that the urge to collect is linked to brain damage and is hence biological. Symptomatic, the author suggests, of a more general move away from psychoanalysis to more ‘hardwired’ explanations of human behaviour. His point, then, is that our understanding of collecting is linked to how we understand the world at any given time. Which, of course, is also one of the primary compulsions to collect in the first place. To prove all this Delbourgo points to the fact that in 2017 The Economist described Hans Sloane as a ‘hoarder extraordinaire’, thus dumping a thoroughly contemporary (to now) condition on the unfortunate accumulator. Sloane, a physician, had published descriptions of Chinese medical instruments, a study of the Jamaican cacao plant and collected manuscripts by alchemists and astrologers to mock the folly of their delusional, unscientific minds. As Sloane had it, according to Delbourgo, the true purpose of natural history collecting was ‘to figure out what species were good for, what they cost, and how to make money off them’. His rise coincided with the rise of Britain’s mercantile class. But perhaps the underlying point is that collecting was a way of distinguishing yourself from everybody else. As Sloane was preparing to dump his collection on the nation, Lord Chesterfield, writing to his son, a bibliophile, in 1750 advised him to rise above the mercantile grubbiness into which collecting had descended: ‘Take care not to understand editions and title pages too well… it always smells of pedantry, and not always of learning’.

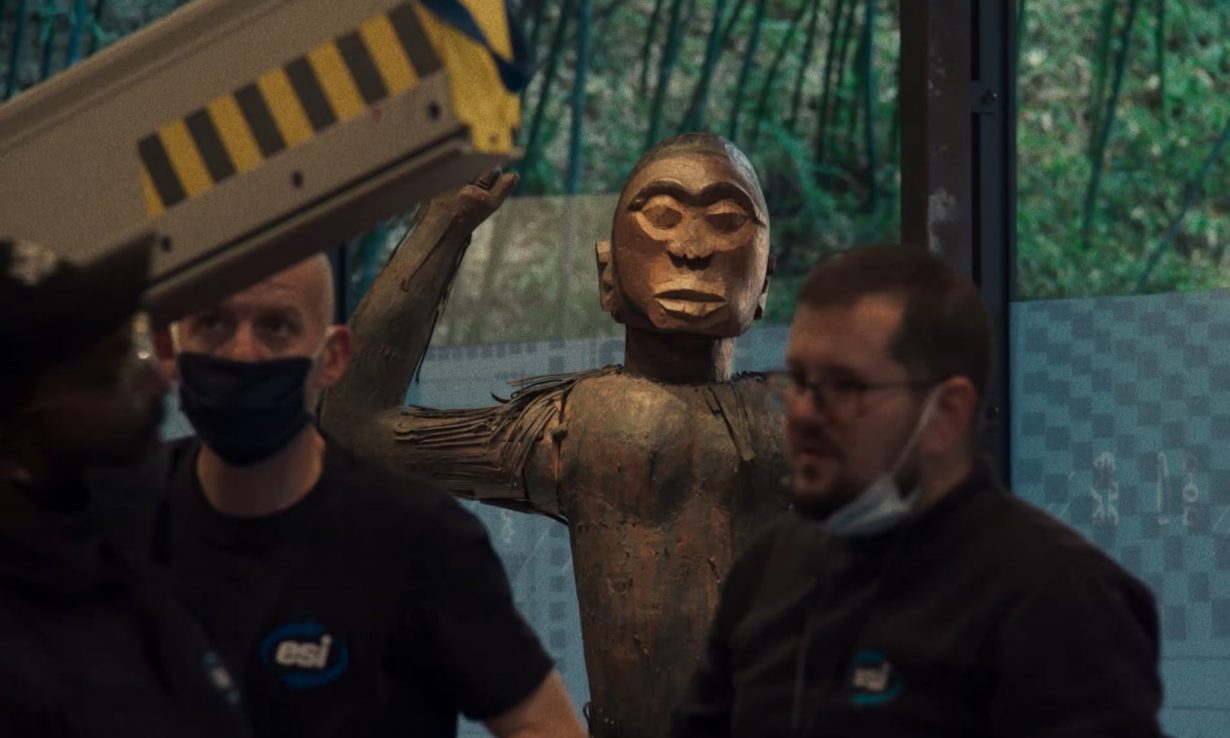

While, during the course of his study, Delbourgo looks at collecting as an expression of particular symptoms – class (memorably, he describes hoarders as ‘those who can’t afford to buy that second house’), colonialism (he quotes Aimé Césaire countering the idea of the civilizing collector by declaring that ‘the world would have been better off if museums had simply never existed’), and violence (the opprobrium heaped on Jewish collectors from the nineteenth century through to the mid-twentieth; China’s Cultural Revolution) – he ends up with the fact that, now, everyone’s at it. If this echoes Freud, it also turns out that the Austrian himself had borrowed the entire strategy that underlay psychoanalysis from art connoisseurs – collecting memories, dreams, ‘slips of the tongue… and Jewish anecdotes’. If Sloane is a hoarder, he’s no different from self-declared ‘garbologist’ and ‘shitehawk’ Ward Harrison, who rummaged through the bins of Hollywood celebrities in order to sell their effluent (actress Natalie Wood’s diaphragm, for example, fetched $35) to avid fans. Sloane’s attempt to professionalise collecting, by commercialising it, found its apogee in the twentieth century in the figure of Andy Warhol (who used to distribute his own trash around various city blocks lest Harrison-types rummage through it). According to Delbourgo, ‘the Warholization of the world, where virtually any cultural object can now possess commodity value, means everything has its price and the collector is increasingly a calculator’. For all the lurid tales (and there are plenty of them) that make Delbourgo’s study such a fascinating read, it turns out, in the end, that collectors are just like everybody else.

A Noble Madness by James Delbourgo. Riverrun, £25 (hardcover)

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.