A new exhibition at Beijing’s National Museum of China attempts to redefine what Saudi culture could and will be

The Saudi Arabian desert might be considered a metaphor for something fluid and ever-changing: the desert’s surfaces shift with the winds, its boundaries blur, and there is a porosity to it – as much in the way that its sands seep into the horizon, as it has absorbed the human traditions that have passed through it. As a rich source of inspiration, it also reflects the diversity of artists who work in the region and its evolving arts landscape.

It’s this sense of deeply rooted cultural traditions and the vastness and possibility conjured by Saudi Arabia’s desert that informs the thematics of Art of the Kingdom: Poetic Illuminations, now on view at Beijing’s National Museum of China. Curated by Diana Wechsler and presented by Saudi Arabia’s Museums Commission, this travelling exhibition assembles over 30 artists who cut across generations and disciplines, each of whom explore different issues related to the region and beyond, including environmental history, cultural tradition, identity and futuristic imagination, offering a powerful, multi-voiced narrative that resonates both locally and internationally. The paintings, installations, videos and performance works here not only represent Saudi culture at present – they are attempts at redefining what it could and will be.

There is, for example, Ahmed Mater’s Golden Hour (2011), part of his decade-long Desert of Pharan photographic series, which captures Mecca mid-transformation with a wide-angle lens that augments the scene’s skyline as it is caught between ancient practice and hypermodern construction. The photograph is a snapshot of urban archaeology, one that reveals the frictions between private human lives, monumental human ambition and the vast wilderness of the surrounding mountains and desert.

Meanwhile, Muhannad Shono’s The Silent Press (2019) engages with language not as a form of direct communication, but with writing as a visual and conceptual form. Drawing from the traditions of writing in the Middle East – where script can be both sacred and artistic – Shono presents a scroll that denies legibility. In fact, as the artist puts it, his work ‘often operates in the space between what can be read and what must be felt’. A space in which ‘legibility is not the only form of truth’. A metal frame holds a flowing ream of paper in place, evoking a stilled printing press. The marks – seemingly random, automatic or accidental – suggest a form of expression that does without the necessity for translation. ‘Illegibility and universality are not opposites for me,’ says Shono. ‘They are often the same thing seen from different vantage points. Something that resists being read in one language may still be deeply understood in another, even without words.’ For the artist, it’s that which cannot be deciphered that pulls the viewer in closer – becoming part of the work itself. ‘The universal emerges not from shared language, but from shared human impulses: to search, to imagine, to complete the gaps with our own memory and meaning.’ For Shono, exhibiting The Silent Press here means being part of ‘a living, travelling conversation’. ‘It’s also a chance for audiences to see the multiplicity within Saudi practice – how different artists approach the world from vastly different angles, yet all rooted in the same shifting ground.’

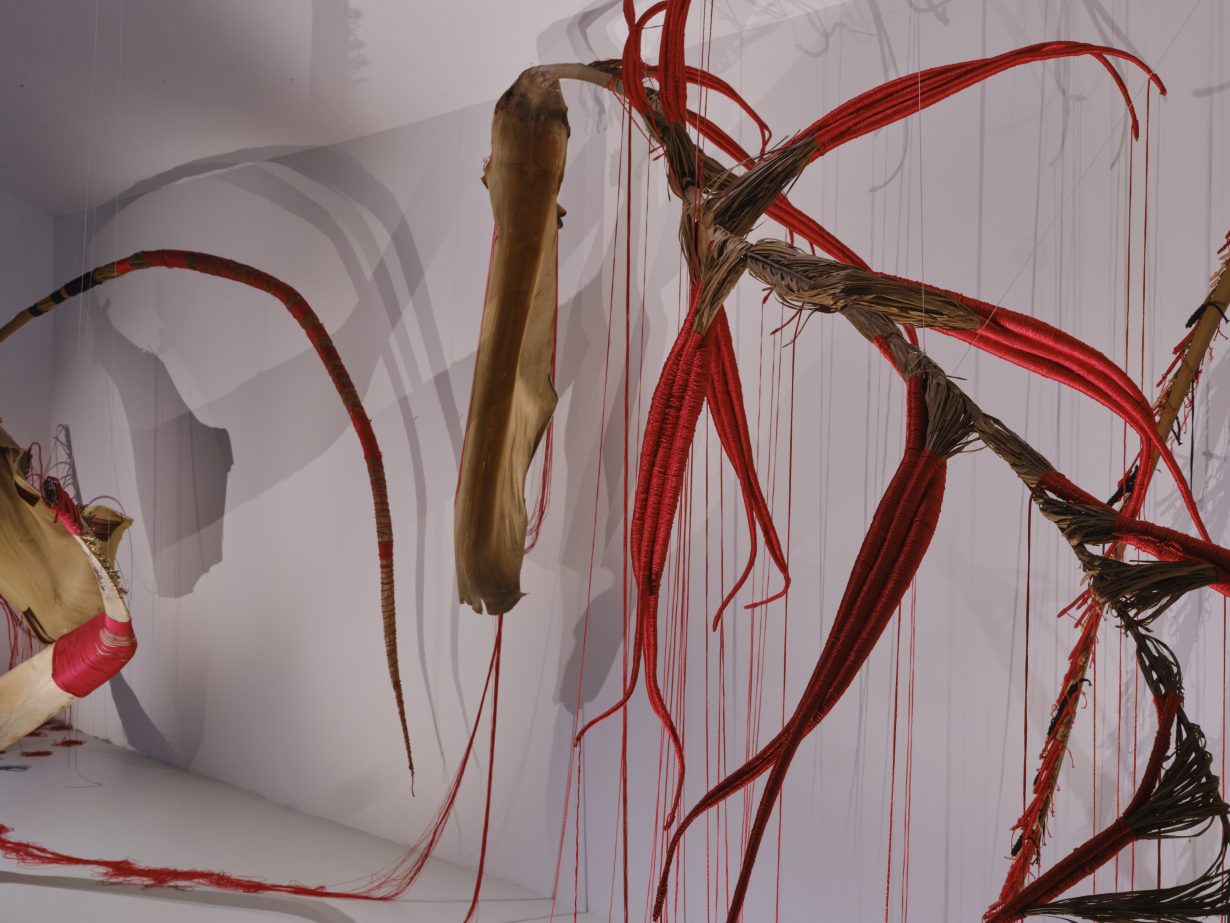

Elsewhere in the exhibition, systems of inheritance come into play – as with Filwa Nazer’s textile installation Five Women (2021), for which the artist turns garments into sculptural biographies. Using dresses once worn by Saudi women, she unpicks, rearranges and re-stitches them into precarious textile forms that hang from the ceiling. These delicate, permeable structures hold layers of memory and the stories of the women who once wore these fabrics, representing a sense of transition and resilience, and remade into something that refuses to settle. It’s this sense of renewal and evolution that’s also present in Lina Gazzaz’s sculptural installation, Tracing Lines of Growth (2022–), but here the artist swaps fabric for leaves, sewing black thread through their veins to map the organic matter’s subtle distortions, folds and flows. The result feels part botanical study, part music score – each line a record of time and the rhythms of growth.

Keep an eye out, too, for Manal AlDowayan’s They Are the Purpose, We Are the Accident IV (2022), a series of sculptures made of Tussar silk, silkscreen ink, acrylic and jute rope, and which appear to sit somewhere between a set of tombstones and geographical rock formations, that explore the artist’s disorientation at discovering unfamiliar histories within her own homeland. The work is partly a response to recent archaeological findings in Saudi Arabia, specifically at the site of the AlUla tombs in northern Saudi Arabia. For the artist, it was the tomb’s huge facades, carved into sandstone, and its conversely small, dark doors that held her attention: these were simple gateways that, for AlDowayan, represented death and the end of a story. ‘Archaeological discoveries in AlUla uncovered traces of lives once lived here, people who loved, lost, and hoped just as we do,’ AlDowayan says. ‘I studied the images and inscriptions they left behind and wove them together with imagined histories shaped by local folklore, poetry, and craft. In Saudi society today, identity is being reshaped in real time, balancing deep roots with a rapidly changing present.’ By confronting these remnants, she questions who holds ownership of history and how we inherit or reinterpret it. ‘This series is my way of letting the past walk alongside that present, reminding us that identity is not fixed in time. It is built from countless human connections, across generations, across distances, across the stories that bind us.’ And, thinking of her work in the context of this touring exhibition, the AlDowayan adds, ‘I’m moved by the idea that this encounter might spark curiosity about the shapes, textures, and stories that shaped me. When we expand the way we see one another, we find ourselves closer, no matter where we come from.’

Beijing’s edition of Art of the Kingdom also folds in a capsule exhibition of modernist works from the 1960s to 80s – presenting Saudi Arabia’s early experiments with abstraction, figuration and form. Seen alongside the newer commissions, they make clear that Saudi contemporary art is built on decades of negotiation between tradition and innovation. What unites the works is a refusal to treat heritage as fixed. Here, the theme of the desert is not as a backdrop but as a protagonist: shifting, absorbing, adapting. The works presented trace the contours of a nation in flux: rooted in its landscapes and traditions, yet constantly redrawing its own map.

Art of the Kingdom – Saudi Arabian Contemporary Art is on view at National Museum of China, Beijing, through 30 October