Nothing in this exhibition is as it seems: everything has a double meaning, speaking for former colonised and former coloniser in separate visual languages. For two decades, Congolese artist/academic Sammy Baloji has investigated his country’s cultural and political history. This latest, gripping chapter focuses on the shaky ethics surrounding colonial collecting and exhibiting, addressing both the connoisseurs who brought DR Congo’s cultural heritage to Europe and the historically voiceless people who created it.

On entering, you’re confronted by a vitrine containing a traditional hunting horn from Baloji’s home province of Katanga. It’s pockmarked with runic scarification, seemingly ornamental but based on a writing system devised to be unintelligible to colonisers. Furthermore, Baloji commissioned this elaborate, supposedly ‘African’ mark-making from metalworkers in Belgium – an allusion to colonial bureaucracy, which required that hunting permits were applied for not in DR Congo but in Brussels.

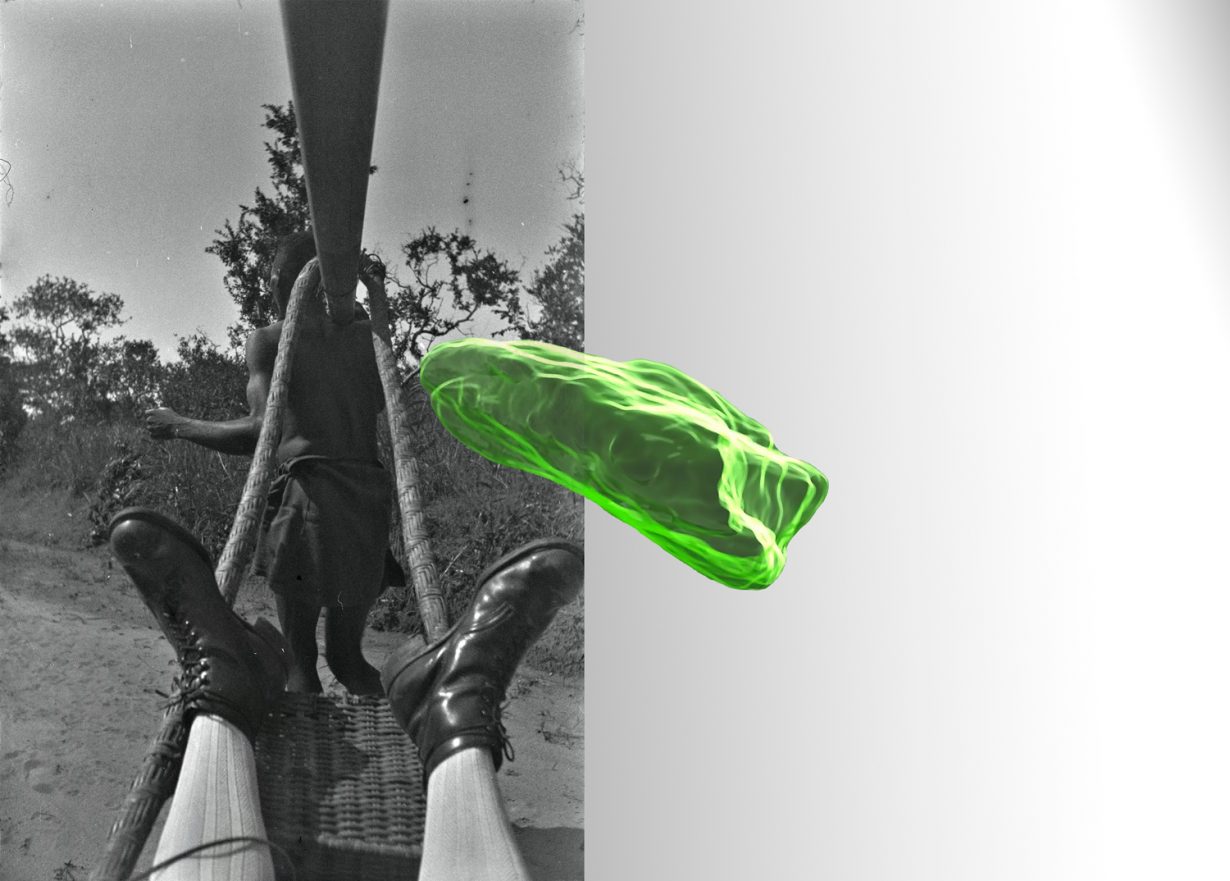

Photographs taken by German anthropologist Hans Himmelheber on a 1939 expedition to Katanga are enlarged and printed onto tall mirrored panels. This specialist on Congolese art was relatively enlightened for the time; nevertheless, we see him carried on a litter by local porters. X-ray scans of objects he collected – rare minerals, ritual sculptures – are printed over his photos, implying that these clinical transparencies can tell us about the original objects’ material composition but not their symbolic value. Your own reflection in the mirror might be an accusation of complicity or an invitation to participate in the discussion. As ever, though, there’s an added dimension: mirrors are significant in Katangese spirituality, being an integral feature of divinatory Nkisi figures.

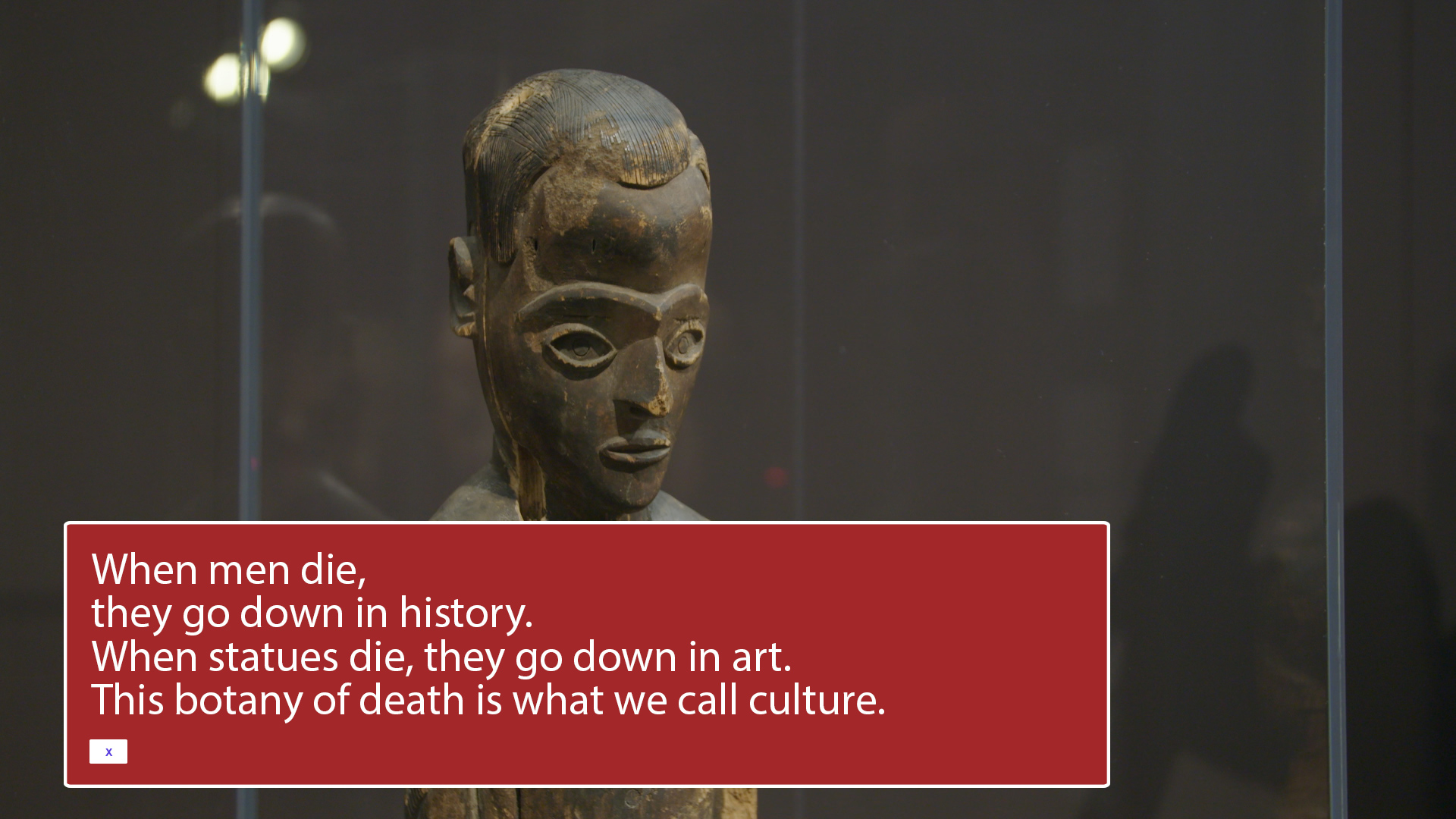

Elsewhere, there’s a projected film that presents writer Fiston Mwanza Mujila reciting Kasalas – prose poems that serve as oral history in Katanga – about its tragic past; an archive of photos and text on a huge touchscreen; and an extract from Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet’s 1953 film Statues Also Die, in which footage of well-heeled gallery goers admiring African artefacts is juxtaposed with a voiceover analysing what it means to look at such sculptures and masks. Where a European might derive aesthetic pleasure, the film suggests, they would likely be blind to the objects’ layers of meaning. Here, Baloji essays a sense of what that meaning is: he knots these disparate threads of cultural misunderstanding into a taut visual shorthand, articulating the problems of displaying colonial-era collections and suggesting how we might eventually overcome them.

Sammy Baloji, Kasala: The Slaughterhouse of Dreams or The First Human, Bende’s Error, at Galerie Imane Farès, Paris, until 13 February 2021