With an increasing glut of water-themed exhibitions, the artworld is taking a compelling, aquatic turn

‘The ocean provides a model to accommodate change and unpredictability, to sway back and forth between, and ultimately to transcend, numerous disciplines,’ writes curator Stefanie Hessler in her essay ‘Tidalectic Curating’ (2020). Proffering a radical premise for an alternative artistic practice, one that looks towards an aquatic, rather than telluric, form of posthumanism, Hessler invokes a term first coined by Barbadian writer and poet Kamau Brathwaite to describe a singular ontology linked to the ocean’s tidal movements – in his words, ‘the ripple and the two tide movement’, which leads, above all, to a rejection of ‘the notion of dialectic’ (and its three-part structure of thesis, antithesis and synthesis). More importantly, Brathwaite’s thinking allows for a construction of identity that moves away from traditional anchors in time and place, to propose a new, fluid form that crossed oceans and continents. It’s this thesis that thinkers and curators like Hessler gravitate towards. As she says, by following the thought of Brathwaite ‘one may find oneself immersed in a hybrid worldview… from the oceans, with their surfaces… as much as in their depths’.

Hessler’s exploration of what has become more generally termed ‘critical ocean studies’ or ‘blue humanities’, by scholars such as Elizabeth Deloughrey (who, along with Hessler, spoke at the Oceanic Imaginaries conference held in March at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam) and Philip E. Steinberg, signals a compelling, aquatic turn in posthumanist critique of the last decade, and one that had been absent throughout large swathes of twentieth-century theory outside the narrow purview of the environmental activist movement. But the current exothermic transformations to the world’s hydrosphere have drastically rewritten the material imaginary of water and its relation to the terrestrial bios. Such changes are clearly visible in the aquatic-themed works of contemporary multimedia artists such as Superflex (Flooded McDonald’s, 2009, and Dive-In, 2019), David Gumbs (Water & Dreams, 2014), Julien Creuzet (mon corps carcasse…, 2019) and Elise Rasmussen (The Year Without a Summer, 2020).

Critical ocean studies’ water-borne imaginaries, however, have ventricles that stretch back far beyond a twenty-first-century eco-poetics. In fact, much of the current artistic fascination with these imaginaries is indebted to a premodern worldview, in which climate was often associated with a sublime, and leaky, volatility. In Gumbs’s experimental film, for example, a fluid collage of vivid, computer-generated colours and effects overlaid on video of tide pools and slow-motion droplets of liquid produces a sensation of immersive virtuality – what might be called the image of digital wetness. Yet Gumbs’s techno-uterine fantasy is largely indebted to Gaston Bachelard’s 1942 text of the same name, in which the mercurial French philosopher conceives of a ‘water mind-set’ that distinguishes between an ancient ‘Heraclitean flux’, and the Socratic metaphysics that dominated Western thought for centuries. ‘[Water] is the essential, ontological metamorphosis between fire and earth,’ he writes. ‘[It is an] element more feminine and more uniform than fire, a more constant one which symbolizes human powers that are more hidden, simple and simplifying.’ For Gumbs, as for Bachelard, the water mindset is closely linked with an atavistic and maternal reverie, an experience that precedes the modern’s emphasis on conscious thought and contemplation.

Despite its reputation as an urtext on water (Bachelard’s Water and Dreams is the second in a four-part collection he published on the elements), the philosopher’s work is not ahistorical; rather, it is rooted in a Romantic tradition of climatology and hydrophilia, which often employed the theme of water to blur the edges between artistic innovation and private fantasy. This lineage includes the Surrealist-inspired, painterly films of Jean Painlevé, Jean Vigo and Jean Epstein; the proto-Oulipo novels of Raymond Roussel; the nautical, poetic-prose of Jules Verne, Charles Baudelaire and Jules Michelet; as well as the musical impressionism of Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel and Lili Boulanger. They helped to prologue what Deloughrey (2020) would describe as critical ocean studies’ ‘rich maritime grammar’ of swirling interdisciplinarity.

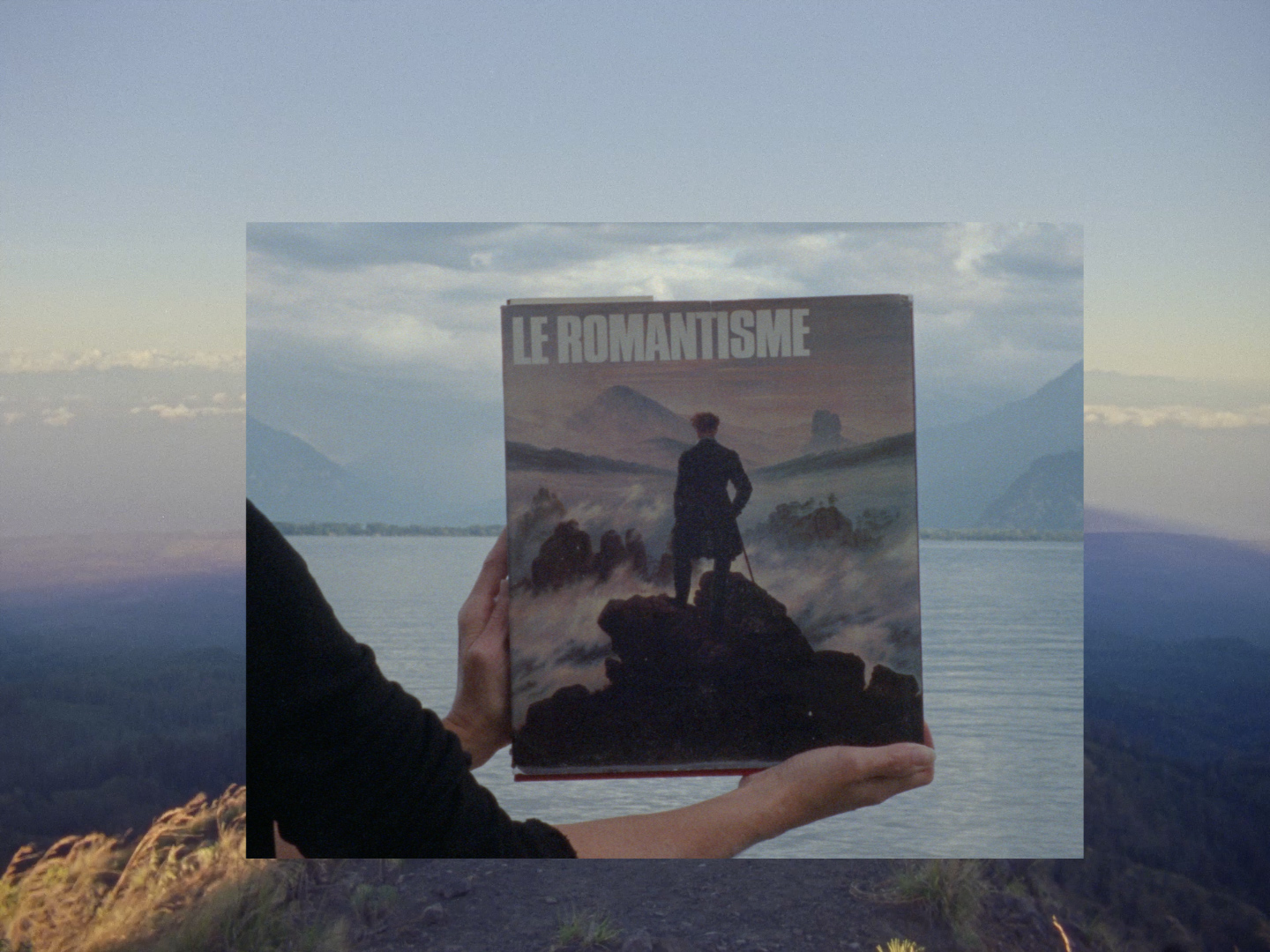

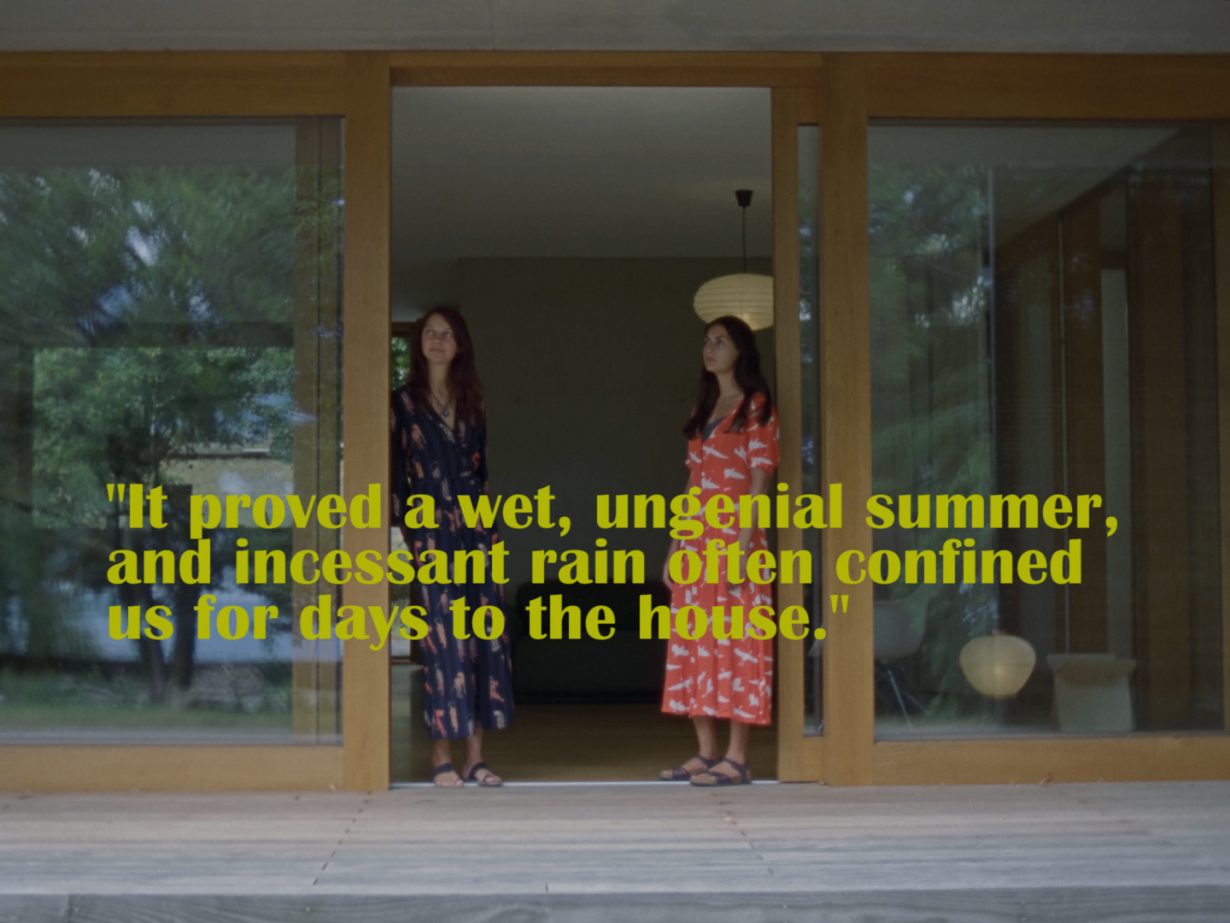

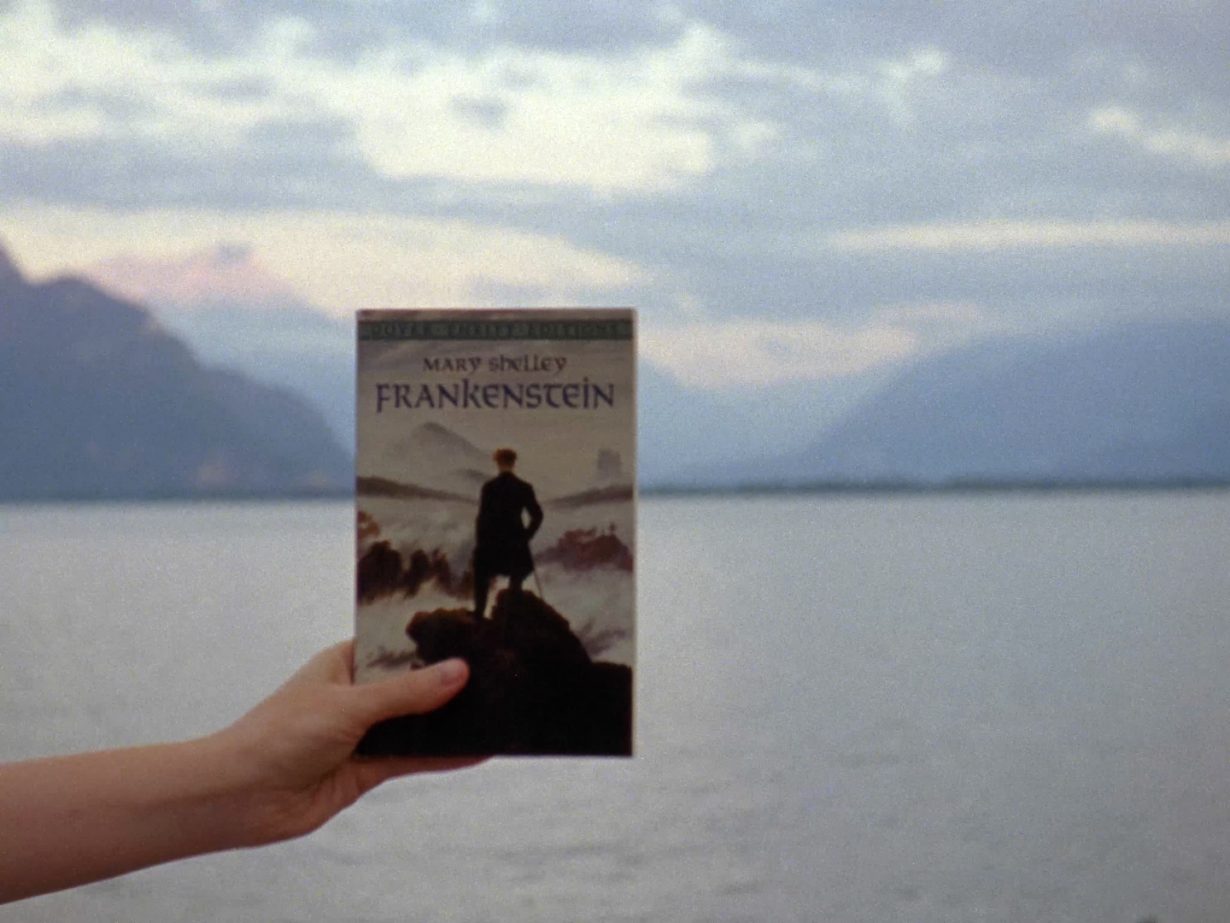

Rasmussen’s film The Year Without a Summer is similarly rooted in a Romantic-era history of water and climate, drawing comparisons between the global crisis of the Anthropocene and the colonial-era crisis instigated by Mount Tambora’s 1815 eruption on the island of Sumbawa. The subsequent anomalies in aerosols, cold temperatures and rain lingered over Earth for years, with food shortages reaching as far afield as Ireland and Switzerland, while inadvertently helping to inspire the late-Gothic tradition in literature and painting. The emergence of murky seascapes and cloudscapes, like Caspar David Friedrich’s Two Men by the Sea (1817) and J.M.W. Turner’s 1816–18 sketches (later published as The Skies Sketchbook), created at the height of Tambora’s atmospheric fallout, show how the century’s increasing fascination with a water mindset was softening boundaries between traditional landscape and colour field, figuration and abstraction. This would reach its culmination in the liquiform abstractions of James McNeill Whistler’s Thames nocturnes and the lacustrine impressionism of Claude Monet.

‘[Maritime mythologies] show us… that the 19th century was an epoch of great speculations about the elements,’ German theorist Peter Sloterdijk writes in Neither Sun nor Death (2011). He points to the expansion of colonialism and the technologisation of shipbuilding for the era’s changing relationships to the sea, in which ‘the sublime was remodeled into the Titanesque… [A]n ocean… appears as a giant matrix, an immense test tube, as an immeasurable incubator.’ It is this contest between Titanic mastery and dissolution that characterised a Romantic poetics of water, or what cultural historian Howard Isham (2004) calls ‘oceanic consciousness’. As the paradigm of that mastery, the ship appeared not only as an image of colonial-era technology but also that of safe enclosure, a finite habitat against the vast, liquid unknown, according to Roland Barthes (1957), for whom Verne’s Nautilus submarine in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) is man’s ideal, seaward living room.

In this sense, the iconography of the ship continues to appear in contemporary works like Superflex’s mesmerising Flooded McDonald’s, a film in which a fast-food restaurant’s self-contained interior is slowly submerged in water, sending all of its trademark scenography, food and plastic wrappings into a swirling vortex. As a miniature parable of a cataclysmic weather event, it also evokes the Romantic fantasy of the sinking ship on turbulent seas, a particularly popular Dutch subgenre of painting further dramatised by both Turner (The Wreck of a Transport Ship, 1810) and Friedrich (The Sea of Ice, 1823–24). Or in the followup, Dive-In, the group erects a coral reef-like megalith in the water-parched Coachella Valley and projects underwater images taken from onboard Dardanella (the research ship of TBA21-Academy, founded by art collector and activist Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, and of which Hessler was a curator, 2016–19), thus creating a cinematic aquarium on the desert floor. While the project suggests both the deep history of the valley’s Lake Cahuilla and the future ruins of an apocalyptic sea-rise, it also recalls eighteenth- and late-nineteenth-century panoramic devices like the Eidophusikon (which often exhibited seascapes) or Hugo d’Alesi’s Maréorama. D’Alesi’s protocinematic tourist attraction was erected for the 1900 Paris Exposition and allowed visitors to sit in a lifesize cruise ship, where they could view a hydraulic backdrop of the Mediterranean shore scrolling across the deck accompanied by artificial fragrances and mechanical soundscapes of sea travel. Like Verne’s vision of the Nautilus, d’Alesi aspired to craft a floating living room for the Romantic’s oceanic consciousness.

Verne’s descriptions aboard the Nautilus also hinted at the nineteenth-century’s orientalised visions of Eastern waters. In the second section of Twenty Thousand Leagues… he writes of the Indian Ocean’s surface as largely uninhabited by ships or sailors except for a floating graveyard of bodies that flows from the Ganges. Despite this, the sea itself is filled with plentiful treasures waiting to be discovered; and sharks, from which Captain Nemo saves a helpless Indian oyster diver, declaring him an oppressed compatriot. This depiction by Verne was based upon a prevalent, Eurocentric travel narrative that reduced the Afro-Asian world’s cultural and commercial infrastructures to an undifferentiated tribal paradise ripe for harvesting. In fact, the Indian Ocean’s trade winds and early shipping technologies had created a littoral network that contested European imperial power in both size and innovation, and contained its own oceanic imaginaries. It was only by the nineteenth century that European traders, buttressed by vast militaries and indentured labour, were able to gain control of South Asian shipping routes and attain global dominance of the oceans. Not coincidentally, the nineteenth century also saw the invention of the historical category of the ‘Indian Ocean’ by Europeans, according to Indian Ocean studies scholar Rila Mukherjee (2013). It is along these same lines that creative mapmaking works like Yonatan Cohen and Rafi Segal’s Territorial Map of the World (2013) and Izabela Pluta’s Oceanic Atlas (vanishing) (2020) reimagine the apparatus of Western cartography in stratifying the borders between land and ocean, home and antipodes, West and East.

Julien Creuzet, mon corps carcasse… (still), 2019, HD video with sound, 7 min 37 sec. Courtesy the artist and High Art, Paris

The European ship was also deeply implicated in the abhorrent activity of the Atlantic slave trade, which reached its zenith at the end of the eighteenth century but contributed to much of the wealth, technology and ideology of the nineteenth-century nation-state and those banana republics of the Caribbean archipelago that served as colonial fiefdoms. The Romantic’s oceanic consciousness contained the repressed memory of African bondage. This is examined in French- Caribbean artist Julien Creuzet’s video mon corps carcasse…, which uses digital animation to simulate the ongoing poisoning of Martinique’s tropical landscape through the contemporary plantation system, imaging the fluid absorption of toxins through the population’s bloodstream. Here, the microscopic liquidity of the black colonial body draws an explicit link between what Hessler, citing both British theorist Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993) and queer studies scholar Macarena Gómez- Barris’s The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (2017), describes as the West’s extractive capitalism and the historical dispossession of the Middle Passage, in which millions of Africans were forced across the Atlantic as chattel slaves. In Creuzet’s film, as in the work of fellow French-Caribbean poet and critic Édouard Glissant, the Romantic water mindset must shed its Western fantasies of fixity and power, and embrace an archipelagic ethics of creolisation if it is to become truly tidalectic.

Critical ocean studies absorbs all of these rivulets of water-based imaginaries in an effort to reconsider their place in the contemporary, terrestrial world. With the increasing glut of water-themed exhibitions and scholarship, it appears the nineteenth-century oceanic consciousness has reemerged as a twenty-first-century water mindset. But the former’s fantasies of immersion and abstraction have also prefigured the impending climatological crisis and a new, drowning mindset in which the human ship floats precariously on a rising sea.

Elise Rasmussen’s The Year Without a Summer (2020), Izabela Pluta’s Oceanic Atlas (vanishing) (2020) and Superflex’s Dive-In (2019) are on show in Oceanic Thinking, at the University of Queensland Museum, through 25 June

Erik Morse is a writer based in Texas