A soundtrack of makeshift domestic instruments mixed with folksongs from back home present a haunting portrait of forced migration in ‘The Song’

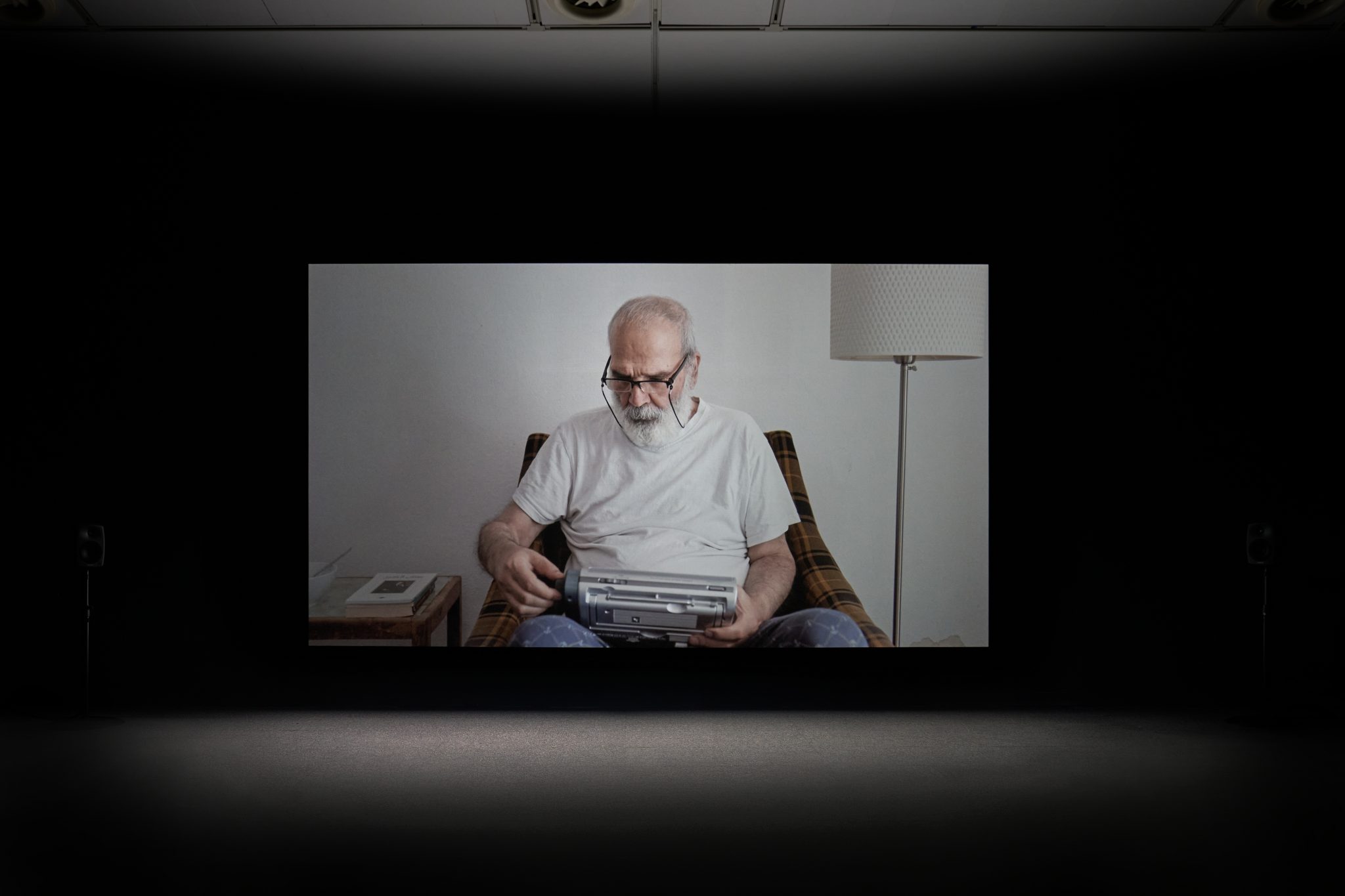

Bani Abidi’s newly commissioned film The Song (2022) is a little over 22 minutes long and comprises two main actors: a grey-bearded elderly man and his sparsely furnished apartment. He arrives on the scene with a suitcase and little else. We see him sitting on the toilet seat trying to sing a song in gravel-voiced Arabic; it sounds as if the first words are an address to his habibi (darling). But he has no one to talk to, and throughout the course of the film we are left with a sense that he has been abandoned, like an alien shuffling around a strange but familiar new planet.

He has brought with him a small stack of books in Arabic, and later brings out a pink plastic mosque-shaped novelty alarm clock, so we can presume he is from the Middle East. From the architecture of his dwelling space, we can also presume that he has arrived in a European city. (The wall-text tells us it’s Berlin, but this is not a work that relies on that kind of reading; for those curious to fill in these gaps, a booklet accompanying the show contains a short fiction speculating on the main protagonist’s circumstances, written by Pakistani-British author Kamila Shamsie.) As the film’s protagonist moves from the kitchen to the bathroom, to a spartan living room outfitted with only a carpet, armchair, side table and lamp, we are left with the impression of an empty world, with the minimal requirements for life.

But there is sound. He investigates the ways in which he can modify the whistle on his kettle by manipulating the lid as it boils. He ‘plays’ a plastic bag first with an electric milk-frother, then another, later, with an electric fan. He makes a makeshift rattle out of cookie-cutters and a loop of wire. Gradually his orchestra expands to include rolls of electrical tape, ducting, electric toothbrushes, wooden batons, cooking pots, plastic bottles and cardboard tubes (some of them used to create a curious listening device attached to his ears). By the end of the film he has combined these things in various ways to create a series of kinetic constructions – devised by London-based artist Rie Nakajima, operating like a scene from Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s The Way Things Go (1987) with an underlying William Heath Robinson vibe – that fill the place with motion and a ticking, whirring, clacking atmosphere.

The film is complemented by the only other work in the exhibition, the installation Memorial to Lost Words (2016), which comprises 24 translations of letters written by a few of the one million Indian soldiers who served in the British Indian Army during the First World War, arranged in a glass-topped table. Some mourn the dead and wounded, and worry about what effect this will have on India (the population will be three quarters women and one quarter men), others warn siblings not to follow them to Europe, or request food from home. Most, however, complain about the cold weather and poor conditions. There are echoes here of the themes of loss, memory and displacement that the central character of The Song seemingly overcomes through his ingenuity and adaptability; though how it went, in the end, for these soldiers is an open question. The key component of Memorial to Lost Words, however, is not the voice of the men, but of the women they left behind in India, which – in the form of folksongs (“Don’t go, don’t go my friend” goes one) and other songs based on selected content from the letters – plays over headphones as you read the typewritten texts. Together the works present a poetic and at times haunting depiction of the invisible effects of conflict and displacement, past and present, and the ways all the senses might be deployed in order that these effects be acknowledged and perhaps overcome.

Bani Abidi, The Song at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, 11 February – 6 May