Before Tomorrow at Astrup Fearnley Museet in Oslo attempts a new acknowledgement of multiple art histories and diverse canons

If you’re thinking that everything comes before tomorrow, you’d be right. Spanning both the museum’s buildings, this is a 100-work ‘selection’ from the collection staged to celebrate its 30th anniversary. That collection has its roots in works first acquired by founder Hans Rasmus Astrup during the 1960s. It also marks a moment of change: the death of Astrup in 2021 and a new acknowledgement of multiple art histories, diverse canons and an artworld that increasingly demands collections that are inclusive of these.

Whether with an unwitting sense of irony or to acknowledge this, Queen Sonja of Norway’s remarks at the opening of the show were delivered in front of Kara Walker’s monumental wall work THE SOVEREIGN CITIZENS SESQUICENTENNIAL CIVIL WAR CELEBRATION (2013), white silhouettes of degrading and cartoonish representations of Black people drawn from the history of violence in the American South that equally speak to the injustices and inequalities so prevalent in our present. Given that the exhibition shares its title with a 2008 Canadian movie (based on a Danish novel) about indigenous peoples who die following contact with white people, perhaps it’s the irony that wins out.

A different (but not unrelated) sense of irony, verging on a knowing comedy, continues through the paintings of Nicole Eisenman, Elmgreen & Dragset’s Gay Marriage (2010; a pair of urinals with interlinked plumbing), the wordplay in Bruce Nauman’s 1972 neon Run from Fear, Fun from Rear (which, in this context, has sinister echoes of Walker’s work) and Louise Lawler’s Michael (2001), a photograph of a pair of art handlers readying themselves to move Jeff Koons’s 1988 lifesize porcelain sculpture (of the late pop star and his pet monkey) Michael Jackson and Bubbles (part of the artist’s Banality series), which itself appears later in the show.

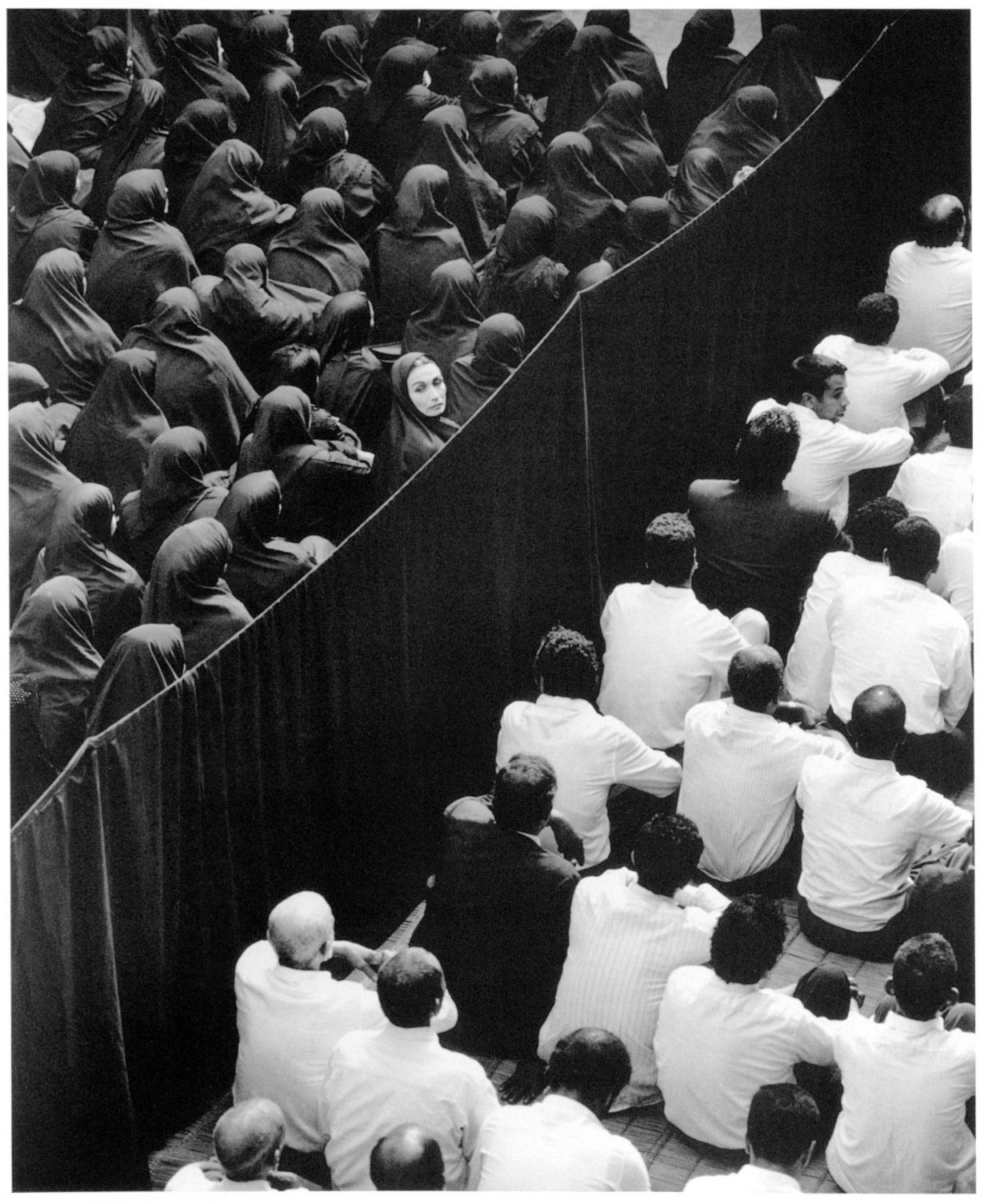

Peppered with works by Koons (including floating basketballs, new Hoovers and ads for Merit 100 Lights), Nauman, Robert Gober, Nan Goldin, Damien Hirst (butterfly paintings, chopped livestock), Sigmar Polke, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall and Christopher Wool, the exhibition at times comes across as a 1980s-to-early-2000s history of conspicuous Western-oriented art-market consumption. But while it certainly is that, it’s also only one history of those times that’s present here: works such as Yang Fudong’s four-minute film Lock Again (2004), which features two Chinese men in 1970s police uniforms in ambiguous scenes of capture and escape apparently trying to flee to some kind of freedom; or Shirin Neshat’s extraordinarily tense two-channel black-and-white film Fervor (2000) – split across gender binaries and featuring an agitated speaker lecturing (although his words are not translated) the separated men and women on the subject of the Quranic tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha (the former resists the attempts of the latter to seduce him), while the film’s main protagonists, a man and a woman in the crowd, exchange furtive glances – give glimpses of the troubles of our times (and suggest they are not so different to those of times past). At the more optimistic end of that spectrum (depending on how you read it) is Gardar Eide Einarsson’s Untitled (FT) (2017), a fabric work bearing the slogan ‘The good old days are gone and they won’t return’. Yet such disturbances to the Western-oriented (and very US-dominated) supermarket sweep are relatively few and far between. And this is not necessarily a criticism; rather a remark on the forces that have shaped the direction in which the collection, in general, leans.

There’s a sense, throughout, that the collection (or the part of it on display) is at times too vast to parse according to one theme or another. And perhaps that too is truly reflective of the world, and the world of art, at large. There’s the simple pleasure of rediscovering painters such as Walter Price and the complex of emotions conjured by Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy-filled Untitled (Blue Placebo) (1991), which is only enhanced and further complexified in a postpandemic era. But perhaps the last word belongs to the newer additions to the collection, a selection of Frida Orupabo’s tacked-together found-photographic collages, which reflect on the Norwegian artist’s mixed-race heritage and Black female sexuality, and which do to the history of photography what Walker’s work does to the historical imagery of the American South. Or Norwegian-Sámi artist Joar Nango’s The same rope that hung you will pull you up in the end (2020), a bent birch pole from which a nooselike golden-copper ring (which also throws off Olympian vibes) is suspended on a reindeer hide and plastic-fibre rope, which perhaps speaks, in its suggestion that exits can become entries, to the hopes for the future of all collections like this. Whether or not those hopes are real or delusional is quite another thing.

Before Tomorrow at Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, through 8 October