An exhibition at Studio Voltaire, London positions the oft-derided artist alongside the hyperreal homoerotica of Tom of Finland, hoping to champion the artistry of both

‘There will be no Beryl Cooks in Tate Modern,’ declared then-Tate director Nicholas Serota in 1996, according to critic Julian Spalding’s recent memoir, Art Exposed. Since the 1970s, Cook, who passed away in 2008, has existed in the British popular imagination as a cartoonist of sorts, rather than as an artist worthy of critical attention. Yet while her distinctive style, including globular figures with large limbs, owes much to that of Edward Burra, the latter enjoys canonical status. Why then, does Cook remain the stuff of novelty calendars and bawdy greetings cards?

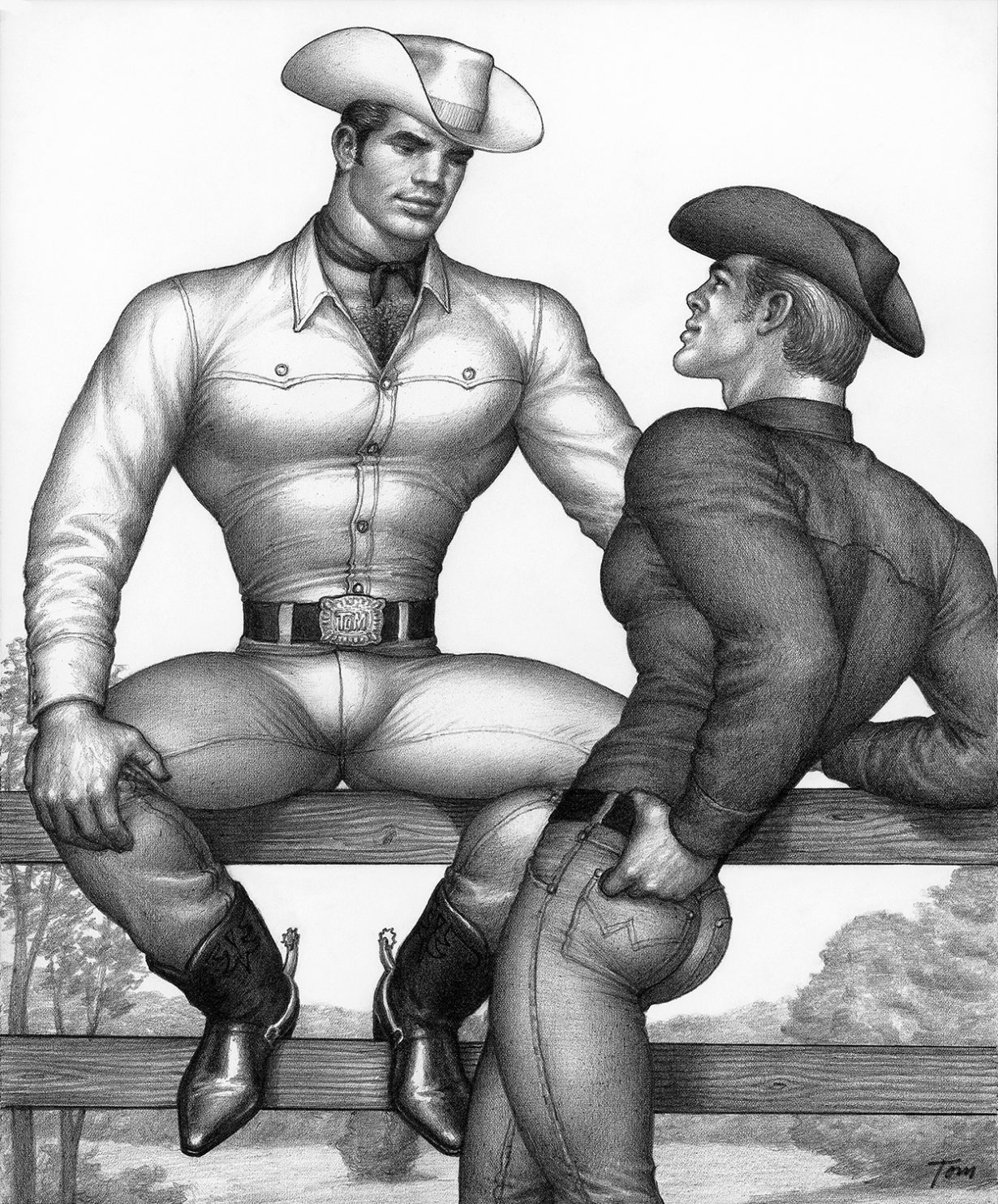

Situating the English Cook alongside Tom of Finland (pseudonym of the Finnish-born Touko Laaksonen) – the great champion of homoerotica – Studio Voltaire’s refreshing exhibition seeks to correct a bias that has relegated one of Britain’s best-loved practitioners to the tradition of the quaint and the kitsch. Finland’s supercharged, sexual utopias – bikers in leather taut from containing erections, pecs so full as to resemble breasts – imagined a life without stigma. Placed alongside Cook, we are invited to see the latter as an artist who also challenged certain orthodoxies.

The accompanying text details both artists’ beginnings in graphic arts, Finland starting out as a freelance commercial artist, Cook first gaining an audience via The Sunday Times Magazine. Examples of her work for the latter are included in the show, along with one of the aforementioned calendars, seemingly to impress upon new audiences Cook’s centrality to, but also somewhat benign place within British popculture of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Institutions slowly came to accept that Tom of Finland’s hyperreal, plasticky Americana offered a critique of homophobia. Cook enjoyed no such reappraisal. Certainly, Finland pursued a riskier course than Cook ever did, prolifically circulating works in pornographic magazines as early as the late 1950s. The show glosses over this disparity: the queer men who enjoyed cruising constituted a minority more persecuted than the albeit trampled and neglected working-class subjects of Cook’s paintings.

Courtesy Studio Voltaire, London

By focussing on works that show scenes of deviance from mainstream conservative values, such as those that celebrate sex workers, for example, the curators challenge the prejudice of many decades that Cook’s style was purely reflective of mainstream mores. For instance, 1987’s Personal Services (a title it shares with a comedy film released the same year) – a jolly depiction of a middle-aged man wearing an underwear set and stilettos being whipped by what might be madame Cynthia Payne – mocks the prurient responses of the tabloid media to Payne’s trial, following the police raid during a sex party the previous year.

A highlight is Lady of Marseille (c. 1990), of a woman, so oblivious to the judgement of others as to be presented with her back to us, dressed head-to-toe in leopard print and accompanied by her three terrier dogs. Mundanity, illustrated by the stack of bin bags piled in front of her, is overwhelmed by the glowing spectacle of her two buttocks tucked barely into a pair of leopard print shorts, painted with a precision that verges on the devotional. In Big Shoes (2006), high street purchases are made monumental, strappy shoes occupying the foreground of the image, idealised and shapely. A manicured hand grasps a cigarette, another a pint, in two gestures that are deft and undeniably elegant.

Here is a yearning – less overt, more innocent perhaps than Tom of Finland’s, but no less intense – for the vein of puritanism and shame that stifled joy and fulfilment to be lifted, and to refocus our attention on the desire that runs through working life. This show makes the case that it was a distaste towards the humour and intellect of the working woman, rather than any supposed triviality in the work itself, that was really driving the naysayers and those, who until now, had succeeded in keeping Cook down.

Beryl Cook / Tom of Finland at Studio Voltaire, London, through 25 August