In Blakytna Trojanda at Hos Gallery, Warsaw, five artists and collectives ask if love, corporeality and society itself can be transformed

At the entrance to Blakytna Trojanda, in which five artists and collectives reflect on the situation of the LGBTQ+ community in Ukraine, white roses stand in chlorine-blue water, petals tinted by its hue. This is a nod by the Ukrainian curators Taras Gembik and Vlad(a) to the 1896 play that shares the show’s title, translated as ‘The Blue Rose’, by writer/activist Lesya Ukrainka. In it, a flower already imbued with romantic meaning acquires greater symbolism via its ‘unnatural’ colour; if such a rarity could exist, could not love, corporeality, society itself be so transformed?

Indeed, writers and words abound here. Slogans graffitied throughout Kyiv by activist group Rebel Queers, declaring ‘Queers Against Kremlin’ and subverting the spelling of ‘Ruzzia’, are frenziedly recreated across the walls. Copies of Queer Ukraine, an anthology compiled after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, are available to read. Therein, Maksym Eristavi extols Ukrainka’s ‘unapologetic and anti-colonial queerness… [which] speaks powerfully to Ukrainians generations down the line’. Next to the roses are a stack of blue-dusted envelopes containing a letter from the writer Oleksii Kuchanskii, articulating the complexity of being an LGBTQ+ Ukrainian during wartime. While acknowledging the indisputable ‘opposition between the defence and the aggressor’, Kuchanskii calls out ‘the limitations of binary divisions of the militarized imaginary’ that make one ‘either a soldier or a woman, a victim or an enemy, a Ukrainian speaker or pro-Russian…’

This resounds in Rebel Queers’ video testimonies, Ukrainian Queer Fighters for Freedom (2022). Ukrainian queer discourse frequently defines the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights as indivisible from decolonial action, claiming that many homophobic laws and attempts at queer erasure stemmed from periods of Russian rule. With only clouds as backdrop and the camera’s under-the-chin angle suggesting a snatched, straight-to-phone moment, a Territorial Defence Forces fighter describes deciding to go to war; “I didn’t know what else I could do for the society I want to live in”, they say, suggesting that “living in [a de facto] Russia despising yourself or living abroad and spending money on therapy just to not kill yourself ” would be intolerable.

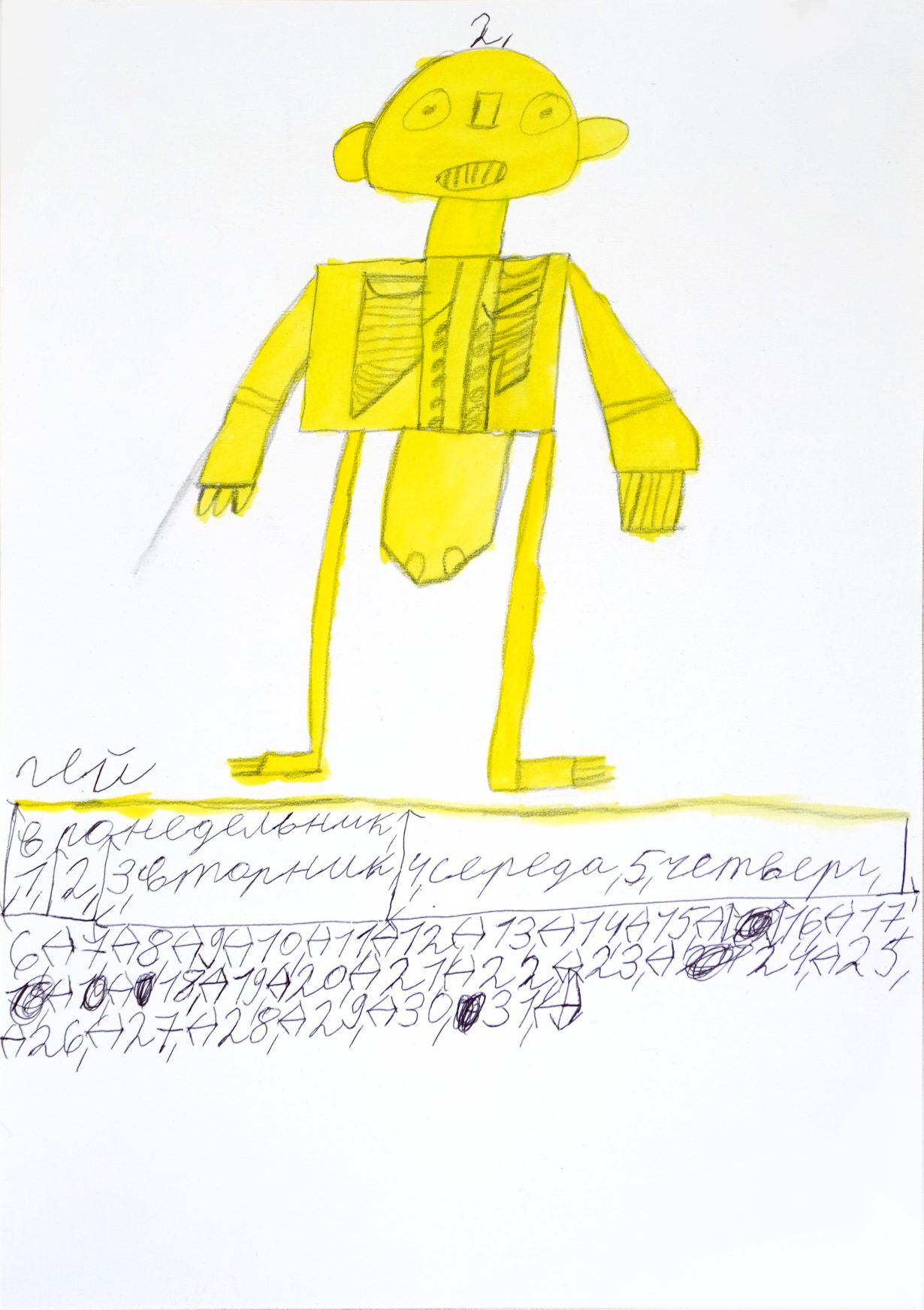

I was told that the exhibition is missing some artworks that were too difficult to send from Ukraine, namely by members of AtelierNormalno, a dozen-strong Kyiv-based collective, half of whose members have Down’s syndrome. The poignancy of the situation is embraced: a mere two reproduction pages from AtelierNormalno’s take on an erotic calendar occupy walls previously reserved for paintings. Announcing the calendar’s publication on Instagram, AtelierNormalno reflected on its appropriateness, ‘but quickly stopped thinking, because erotics, love and the body now have even more power for us than ever’. The pages’ drawings, by a homosexual man, depict a blocky frontal figure with an abstract protuberance between his legs. Underneath, the word ‘Gay’ is followed by a scrawled list of days and numbers that scramble the legibility of conventional calendars: a peal of queer disorder.

Elsewhere, Lviv-born artist and filmmaker Jan Bačynsjkyj’s wall-mounted artworks fashion old furs, feathers, broken toys, beads and textiles into masks, Madonnas and cute-meets-Krampus roadkills. In an interview, Bačynsjkyj described these works as being ‘parasitic on traditional forms’, recalling a now familiar trope of artmaking that taps folk practices for queer customs and radical potential. Menacing yet hilarious, they thrum with engrossment and an eye for sifting through dreck for alternative totems, especially felt during wartime, when material and spiritual life is laid to waste. A patchworking process echoes in Oksana Kazmina’s split-screen videowork Mutation. Neither a Fairy Tale nor a Musical (2020), wherein dialogues from an online residency conducted during the pandemic via the messaging service Telegram accompany various scenes; a beaming ballroom dancer’s fluid movement becomes increasingly convulsive; a semi-naked masked figure frolics through a rural landscape; a group of queers, not especially young or ‘sexy’, retell dreams with deadpan delivery in a studio in Mariupol, now surely destroyed. Each absorbing segment leans into the title’s ‘neither/nor’, refuting the full bloom of a musical or fairytale’s course, yet somehow tingling with alternative magic.

Blakytna Trojanda nurtures such expansiveness, clearly curious about a regional discussion of queerness beyond Ukraine’s metropolitan centres, and certainly beyond dominant Western articulations. To return to Kuchanskii, it reminds fellow travellers that we must strive ‘to communicate with our own differences’; a sentiment shared with Audre Lorde, who also knew that ‘without community, there is no liberation’. Our most deadly enemies will always target this fragile truth.

Blakytna Trojanda at Hos Gallery, Warsaw, 15 June – 15 July