In the next iteration of their project examining the history of literary production, Brass Art regenerate Woolf’s writing shed at Home, Manchester. It’s an exercise in attention – and misdirection

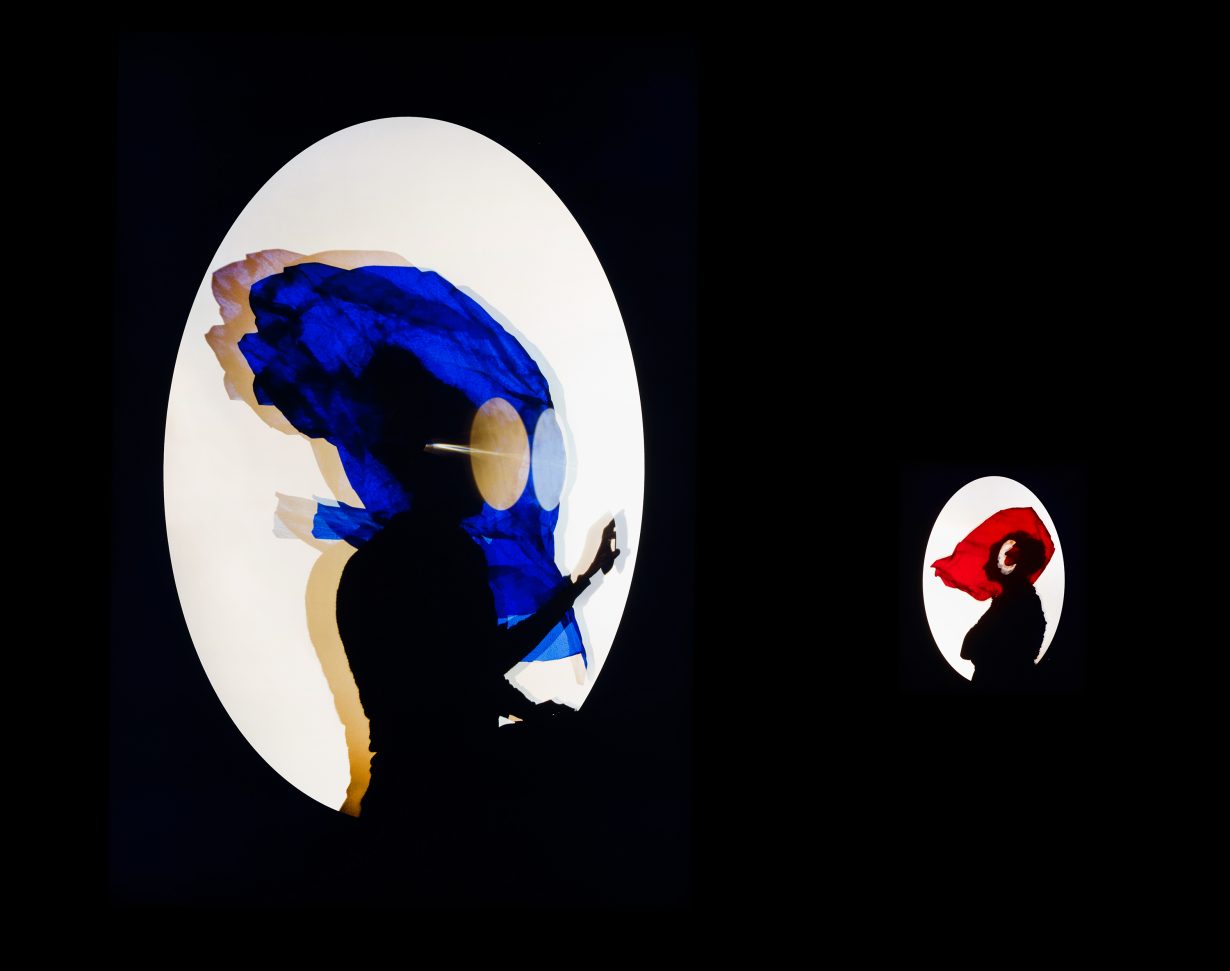

As Brass Art, artists Chara Lewis, Anneké Pettican and Kristin Mojsiewicz work across sculpture, drawing, video and photography to create installations often centred around largescale projected images. Using light to cast shadow, transform materials or offer fleeting or fragmentary glimpses of interior spaces, objects and the artists’ own bodies, their works elicit a sense of doubt or unease in the viewer, reflecting their interest in how to visualise psychological states.

The heart of this exhibition and the largest new work is this voice; this life; this procession (2024), the most recent chapter of Brass Art’s decade-plus examination of historic sites of literary production, following earlier works made at the Freud Museum (Sigmund Freud’s London home), in 2015, and the Brontë sisters’ museum in Haworth in 2012. this voice… takes as its subject Virginia Woolf ’s writing shed at Monk’s House, Rodmell, East Sussex. In her 1929 essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’, Woolf famously asserted that a woman must have money and a room of her own in order to write, a statement that has become integral to feminist analyses of the relationship between material conditions and creative practice. Woolf ’s shed, set apart from the house, seems to be a literal manifestation of her plea. Access to the shed is usually limited to a glimpse through a viewing window, but Brass Art were allowed to scan themselves, the shed’s interior and the surrounding garden using 3D scanners. Here, the two-channel video combines images of a 3D model of Woolf ’s shed, hovering, turning and spinning in space, with movements of the artists’ bodies within the shed, captured momentarily and fleetingly. The overlay of naturalistic or photographic imagery and more obviously digital and pixelated forms suggests a sense of crossing boundaries and thresholds. According to the artists’ accompanying notes, this reflects Woolf ’s own writing strategies, of fragmented reality, stream-of-consciousness and defamiliarisation. The rustling of cellophane, recorded onsite by the artists, is the basis for an immersive soundscape by electroacoustic composer Annie Mahtani, providing an uncanny aural accompaniment to the visual material.

Courtesy the artists and Home, Manchester

this voice… (the title taken from a passage in Woolf ’s 1925 novel, Mrs Dalloway) acts as a thematic lynchpin for the otherwise formally disparate works gathered here. In the Apparition series (2014–24), for example, cellophane appears as a material, as do images of the artists. In these photographs and short, single-channel looped videoworks the artists appear as grotesque portrait silhouettes, hovering between human and monstrous forms (enlarged heads, distorted figures, a lack of clear delineation between human body and costume). As with this voice…, Apparition references another modernist creative practitioner, in this case the American theatre designer and poet Florine Stettheimer (1871– 1944), who used cellophane in her set designs for works such as Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s 1934 opera, Four Saints in Three Acts.

The link between this voice… and the works that form Apparition is clear (revisiting modernist literary history; feminist creative practice; figuration; implied narrative), but the large sculptures of the torrent of things grown so familiar (2024) seem at first arbitrary or misplaced. Materially, we’re again faced with the crossing of thresholds or the passing-through of apparently impermeable boundaries between physical and digital space – silver Mylar sheeting creates the surface of what appear to be gigantic erratic boulders. Hung from the ceiling and grounded by cast bronze hooves, they are both absurdist and eerie, apparently solid yet, up close, flimsy and transparent. What do these mountainous forms have to do with the other works? The title is taken from a passage in Woolf ’s final novel, The Waves (1931), a continuous monologue recounting the lives of six characters from childhood to middle age. These geological forms capture something of the rush and passage of time, their core illuminated by coloured lights that seem to pierce the semipermeable ‘rocky’ surface. The final area of the exhibition assembles research sources, preparatory works and models dating back to 2002, alongside a constellation of inkjet prints that make visible the artists’ processes, methods and materials used in the development of the exhibition, while the final work, Click (after Hogarth) (2018), a neon animated drawing, seems to act as a bookend to the show. Drawn from a hand gesture in William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress (1732), the click of a woman’s fingers distracts one suitor from the departure of another in the original narrative. Here, it is as though the artists gesture to their own methods and sources. It’s a fitting symbol with which to close a show so concerned with vision, attention, misdirection and the ways in which resourceful women have found ways to claim the space and time to pursue their endeavours.

rock, quiver and bend at Home, Manchester, through 1 September