Burnout by Hannah Proctor maps a global community of what people did next

At 10pm on 12 December 2019, I burst into tears, and didn’t stop crying for weeks. I’d spent long days campaigning for Labour during the British general-election campaign, and years supporting the party’s social democratic project in my writing, demonstrating about the Grenfell Tower disaster and the rise of fascism. The scale of our defeat was unbearable. I raced through Kübler-Ross’s grief cycle, skipping denial (the exit poll was all too clear) and bargaining (what was the point?), going straight to anger and depression. The tears stopped around February, and I began to recover my energy. I channelled it into a futile attempt to stop the right taking back the Labour Party. My fleeting hope of renewal was crushed, however, by the COVID-19 lockdowns, which made it impossible to organise against the Blairite restoration or the triumphant Conservatives’ authoritarian anti-protest laws. I collapsed into an exhaustion I’ve felt ever since, wondering if I would ever recover – and if so, how. Without quite knowing it, I’d been waiting for a book like Hannah Proctor’s – ‘addressed to burnt-out comrades’ – all this time.

Burnout isn’t a guide to curing ‘the emotional experience of political defeat’; while it offers some recommendations from those whose movements were crushed or collapsed, from the Commune of Paris to the present, the main consolation it offers is that of feelings shared across time and space. Its chapters are structured around the emotions that campaigners commonly feel in the wake of defeat: melancholia, nostalgia, depression, burnout, exhaustion (and the ‘exhaustion that comes from fighting exhaustion’s causes’), bitterness, trauma and mourning. Proctor pays close attention to political histories, of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, the Commune of 1871 and the miners’ strike of 1984-85, second wave feminism and the Black Panthers, and many others. She questions the left’s criticism of psychotherapy as seeking to reconcile individuals with a sick society, rather than encouraging them to change it, highlighting times when therapy helped people or groups understand their struggles and ready themselves to fight anew. She is generous to Huey Newton’s concept of ‘revolutionary suicide’, where people subordinating their physical and mental health to the movement – this, she says, ‘is not a death wish but expresses the desire to live in a less deathly world’, even if it may mean being crushed in the process. Such realism, Proctor argues throughout the book, is vital for radicals if they want to head off the psychological collapse that comes with the raising and crushing of hopes.

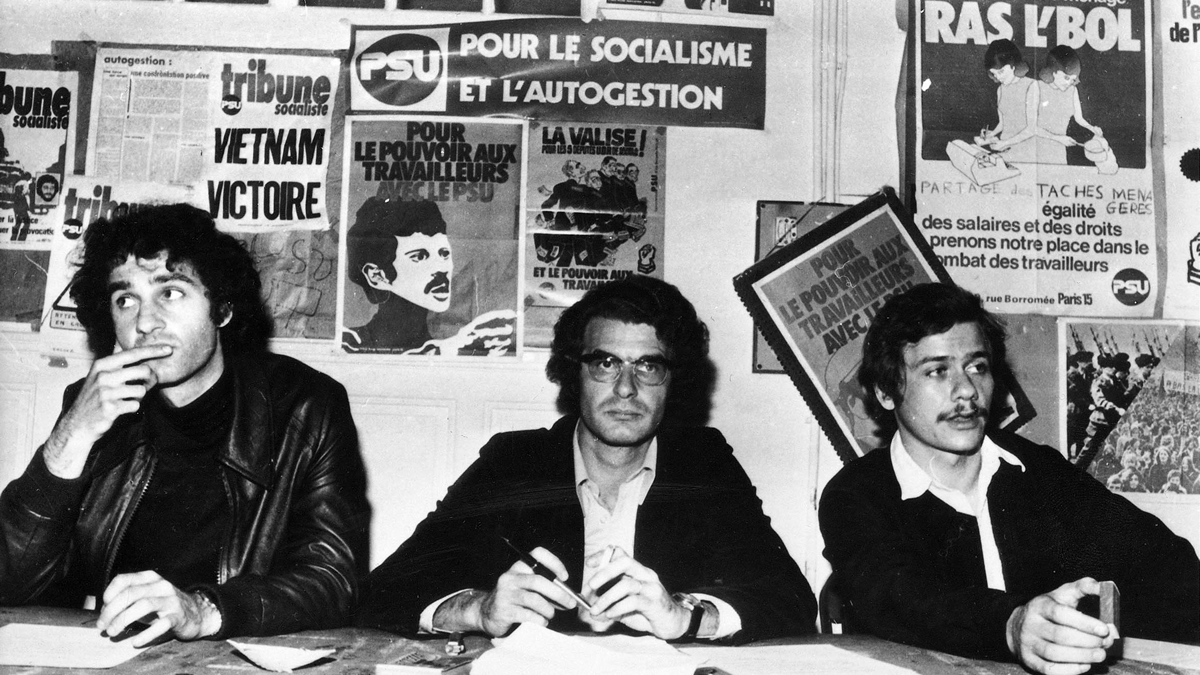

She also analyses a wide range of literature and film, looking at how fiction, memoir and documentary can allow us to access different psychological aspects to defeat on individual and collective levels. She does this not just to understand how specific works have explored the reasons for people’s reactions to defeat (in particular the documentaries about the Weather Underground or the Japanese Red Army of the 1970s) and for what they did next, but to think about how revolutionary activity shares parallels with art practice – how pursuing it can make oneself an outsider with severe financial and psychological consequences, with posthumous recognition being scant reward for a lifetime of (often thankless) struggle. Radical activity, like the process of making or enjoying art, often unleashes explosions of energy – notably in Paris in 1871 and 1968, when artists, writers and filmmakers wanted to involve themselves in insurrections. In a book written out of ‘suspicion of rhetorical appeals to hope’ after a defeat, Proctor dives into participants’ accounts of depression, disengagement, recrimination and suicide. Her chapter on nostalgia hits just as hard as post-’68 films such as Romain Goupil’s Mourir à trente ans (Half a Life, 1982) or João Moreira Salles’s In the Intense Now (2017), which follows Chris Marker’s A Grin Without a Cat (1977) in charting the generational defeat of worldwide insurgencies.

In her exploration of artistic responses to the disasters of the 1970s and 1980s, Proctor proves especially acute. She explores in depth the work of Chilean documentary filmmaker Patricio Guzmán, who made The Battle of Chile (1976-9) about the Popular Unity government and its death in the CIA-backed Pinochet coup, as a case study in how to process trauma through art. Burnout achieves commendable synthesis between its argument and sources, but this section stands out: Proctor quotes Guzmán talking about how he had to deal with his personal history before he could make work on Chile’s national memory, and how his filmmaking demonstrates Freud’s ‘compulsion to repeat’ traumatic moments – ‘to go back to a time before the ruins and ashes’. Guzmán’s film cycle began with Chile, Obstinate Memory (1997), where he returned from exile to interview people who appeared in his earlier films about how they survived Pinochet’s regime, before making a trilogy that more obliquely dealt with the thousands of ‘disappeared’ people and their relatives’ search for their remains. In My Imaginary Country (2022), Guzmán documented the radical surge of 2019, when protests against subway fare rises turned into an uprising against the neoliberalism introduced in Pinochet’s constitution, with feminist art group Las Tesis being prominent on the streets and in the film. Guzmán ends with the election of left-wing activist Gabriel Boric, and a note of hope that the constitution will change – hope that has died amid ineptly handled referenda and right-wing opposition, in a major setback for one of the last of many radical movements throughout the world during the 2010s.

The collapse of hope in so many of the junctures that Proctor describes, from the loss of the Spanish Civil War to the shattering of the Labour left at the start of the decade, does not mean giving up the struggle. Proctor closes by quoting Mike Davis, who argues that hope is not ‘a necessary obligation in polemical writing’, urging us to ‘Fight with hope, fight without hope, but fight absolutely’. The movements Proctor – and I – are interested in, and became involved with, sprang from an awareness that social conditions were bad, had got markedly worse during our lifetimes, and looked likely to get worse still in future. Whether we fight that through activism, electoral politics, writing, filmmaking, art or some other way, we cannot let optimism of the will blind us to the fact that our fights will not be painless. The more people are writing books like Burnout, the better we might overcome our pains, and remain in the struggle.

Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat by Hannah Proctor. Verso, £14.99 (softcover)

Juliet Jacques is a writer, filmmaker and footballer based in London