“I can’t believe this is finally happening.” “I can’t believe this exists in Hong Kong.” These were some of the frequently uttered phrases during the preopening event for Hong Kong’s brand new M+ Museum of Visual Culture, and they help convey the sense of surreality that infused it. After all, the M+ project, promoted as Asia’s answer to London’s Tate Modern, New York’s MoMA and Paris’s Centre Pompidou, first launched more than a decade ago and reached this moment after numerous and very public construction and bureaucratic delays.

The museum and its collection are the first of their scale and kind in Asia, filling a void in the city’s local cultural landscape and attempting to legitimise Hong Kong’s status as the region’s art centre. A neobrutalist structure on the West Kowloon harbourfront, the museum – outfitted with high ceilings, vast grey concrete interiors and black railings – induces both a feeling of wonderment and a sense of déjà vu. For while it represents something of an architectural novelty in Hong Kong, it is nevertheless reminiscent of Tate Modern (the 2000 redevelopment and 2017 extension of which were designed by M+ architects Herzog & de Meuron).

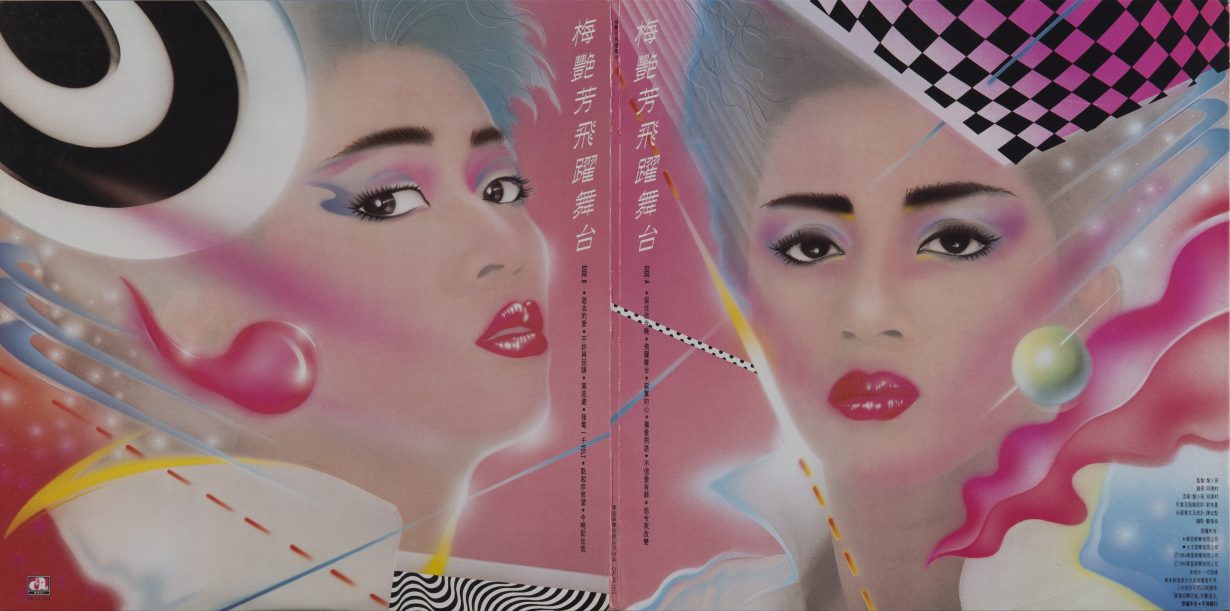

© Capital Artists Ltd.

The similarities end with the architecture, however. The new institution’s collection and projected curatorial aims and perspectives differ greatly from those of its Western counterparts. M+ strives to present contemporary art-history from varying Asian perspectives, with a focus on showcasing art from Hong Kong and the greater China region. Its collection contains 50,000 artworks by 777 artists, out of which 76 percent are Asian (or of Asian descent). The opening displays feature 1,500 artworks from among the holdings, arrayed across six exhibitions, one of the most sizable and anticipated of which is the M+ Sigg Collection, featuring works that trace the history of Chinese art through the postwar period. Though even that display has been not without hiccups: the collection includes a work from Ai Weiwei’s Study of Perspective series (1995–2017), depicting the artist holding up his middle finger to politically significant monuments in various cities, including Beijing. Earlier this year, conservative politicians highlighted the work as potentially violating the ambiguous National Security Law (implemented in the summer of 2020). Since then, the work has been removed from the museum’s website and is not part of the current exhibit.

Concerns about censorship dominated the press conference on the preview day. In response to multiple questions about the issue, Henry Tang, chairman of the board of the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority (and the chief secretary of Hong Kong from 2007 to 2011), of which M+ is a part, emphatically stated that artistic expression was not above the law, and that the museum would comply with the city’s laws, leaving an open question as to how and to what extent censorship will be enforced. Other works by Ai were on view: Whitewash (1995–2000), comprising an array of Chinese Neolithic vases partially dipped and/or painted in white paint. The work essentially challenges the whitewashing of history, and takes centre stage in the M+ Sigg Collection display.

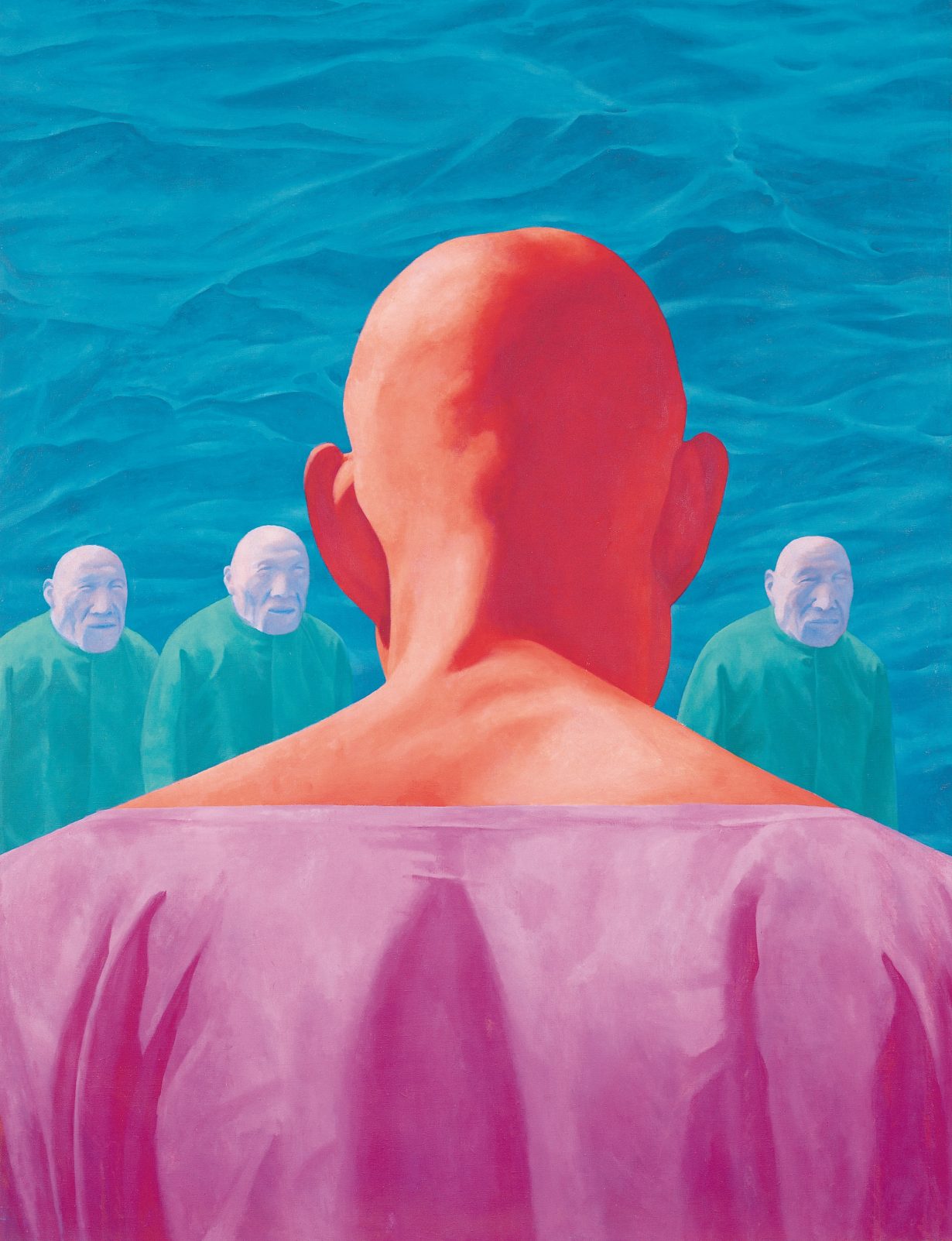

Initially, that exhibition (titled M+ Sigg Collection: From Revolution to Globalisation) appears to represent an auction preview circa 2008, the year that marked the global commercial boom of Chinese art. It features works by some of the celebrated names and works to emerge from that period: Wang Guangyi and Zheng Fangzhi; Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline – Big Family no. 17 (1998) and Fang Lijun’s 1995.2 (1995); and multiple works by artists from the avant-garde Stars Art Group. However, the deeper one delves into the display, the more works by artists crucial to defining Chinese art history from the 1970s through the 2000s are uncovered, revealing a richer historical narrative. Huang Yong Ping’s Six Small Turntables (1989) is a hidden gem, manifesting the artist’s signature infusion of Buddhist and Taoist philosophies with a Dada-influenced conceptual approach: six wooden turntable platters are stacked in descending order of size and placed in an open black leather case, attached to which is a piece of paper explaining how the work functions as a roulette for determining the conditions – material, composition, etc – of future artwork creation.

Courtesy the artist and M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong

Amid the overwhelming number of works on view, Civilisation Pillar (2001), by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, provides a particularly visceral impact. The pillar, comprising human fat, wax and metal, and reflecting society’s obsession with appearances, materialism and excess, induces an unsettling, nauseating sensation.

In stark contrast, the exhibition titled The Dream of the Museum focuses on a conceptual, and aesthetic (and perhaps more costly) curatorial approach: the bamboo-covered walls of the gallery transform the space into a tranquil one, distinguishing the works on view from those hung on white walls in the museum’s other spaces. The exhibition explores how contemporary artists appropriate found objects and build on the legacy of pioneers Marcel Duchamp, Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono (among others). Danh Vo’s marble Venus torso (Untitled, 2018) with an attached modified replica of Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. Rasée (1965, an image of the Mona Lisa with a moustache painted on her face), sits beside Hong Kong artist Trevor Yeung’s delicately encased sea snails in Three to Tango (2014). Behind Zheng Guogu’s luminous orange take on a thangka, Yoko Ono’s monochrome white chessboard Play it By Trust (1966/1986–87) lies across from Morimura Yasumasa’s A Requiem: Theater of Creativity / Self-portrait as Marcel Duchamp (Based on the Photo by Julian Wasser) (2010), in which the artist transforms himself into both Duchamp and writer Eve Babitz playing chess with each other.

magnesium, 17 x 76 x 76 cm. © the artist. Courtesy Carl Solway Gallery,

Cincinnati

Courtesy M+, Hong Kong

Other highlights include special exhibitions and single gallery installations, such as Antony Gormley’s Asian Field (2003), comprising 210,000 clay figurines made by 350 residents of a village in Guangdong. Here the artist replaces himself with a community, with the intention of questioning who is allowed to occupy cultural spaces, a significant consideration in reshaping long-held perspectives. While his intention still results in his concept occupying the cultural space, it also activates, in the context of the museum in general, an awareness of the process of looking, as the artist’s field of figures return the viewer’s gaze thousandfold.

Crowded by photographers, VIPs and influencers attempting to get the perfect Instagram shot, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s Crucified TVS – Not a Prayer in Heaven (Traditional Chinese/Cantonese English Version) (2021) affirms and captures the ludicrous nature of the world’s chaotic condition, striking a resonant chord. Theatrically suspended high above the gallery space, TV screens assembled in a crucifixlike shape (recalling Nam June Paik’s TV Cross, 1966) flash phrases such as ‘A world on fire is like a life in hell’, inducing a fervent atmosphere. As some of the first artists to engage with the internet, the duo (South Korean Young-Hae Chang and American Marc Voge) are pioneers in their use of that medium, in much the same way as Paik was to TV.

digital video. Photo: Dan Leung. Courtesy the artist and M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong

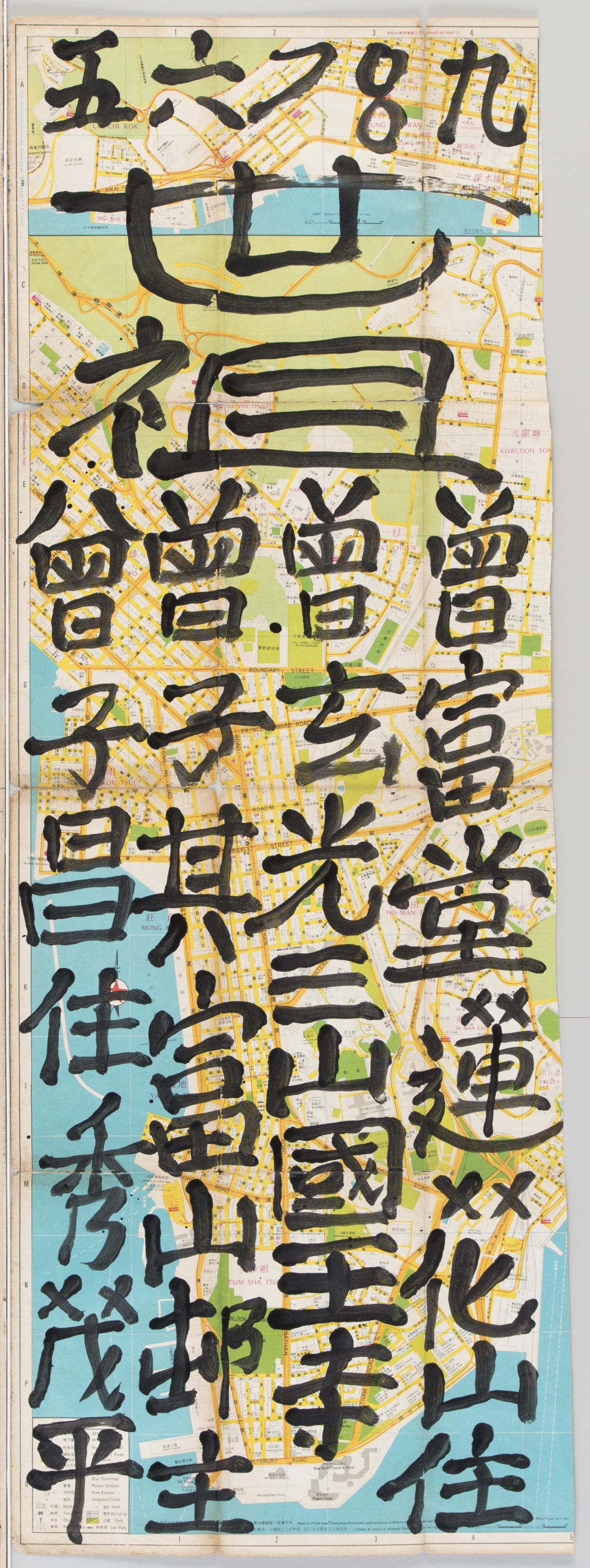

For Hong Kong artists in particular, the existence of M+ provides a kind of institutional recognition they haven’t known before. The exhibition Hong Kong: Here and Beyond features work by local artists (136 of the 777 artists whose works are part of the collection are from Hong Kong), and an early gauge of the extent to which M+ will (hopefully) uphold its promise to serve the local art community. Centred on four themes, ‘Here’, ‘Identities’, ‘Places’ and ‘Beyond’, the exhibition aims to shape a holistic, rather than chronological, understanding of the city. A work by the late Tsang Tsou-choi (aka King of Kowloon; self-taught, and the equivalent of a street artist during his time), Untitled pair of doors (2003), inscribed with his signature calligraphic aesthetic, opens the exhibition and serves as a metaphorical gateway to Hong Kong’s art history. A work by another self-taught artist, Yeung Tong Long, wields a hypnotic effect, his 2.4m-high perspective painting The Floor (2014), depicting his studio floor as almost unending, and warped – a projected fantasy specific to the typically small and confined spaces in Hong Kong. In dialogue with this painting is Kacey Wong’s installation Paddling Home (2009): self-exiled to Taiwan earlier this year, Wong built a ‘micro-home’, resembling a minihouse on a raft, with materials typically used to construct residential buildings, and launched it into Victoria Harbour as a critique of unaffordable and compact housing in the city. In a way it offers a real-life critique of the numerous architectural models and drawings that are included in the exhibition as a trace of the city’s urban development.

Whatever the implications of Hong Kong’s political future may be, the city now has itself a world-class facility that undoubtedly strengthens its arts infrastructure and diversifies its cultural landscape. As importantly, at a time when established institutions are being criticised for exclusivity and a lack of perspectives, and are being forced to reckon with their own problematic colonial histories, M+ provides a potential platform from which to rectify that. While M+ will continue to face challenges, this opening series of displays suggests that it is in a position to develop new and relevant ways of documenting local and Asian art histories.