‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers’ at London’s Design Museum offers some clues as to the fate of the ‘blockbuster exhibition’ in post-pandemic times

A piece of wall text inside the Design Museum’s newly opened exhibition Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers asks: ‘Can a sound without words say anything?’

The show answers with a resounding ‘yes’ by way of an engaging exploration of electronic music’s evolution and enduring cultural influence. But the question also evokes the challenges of exhibiting popular music in the museum space.

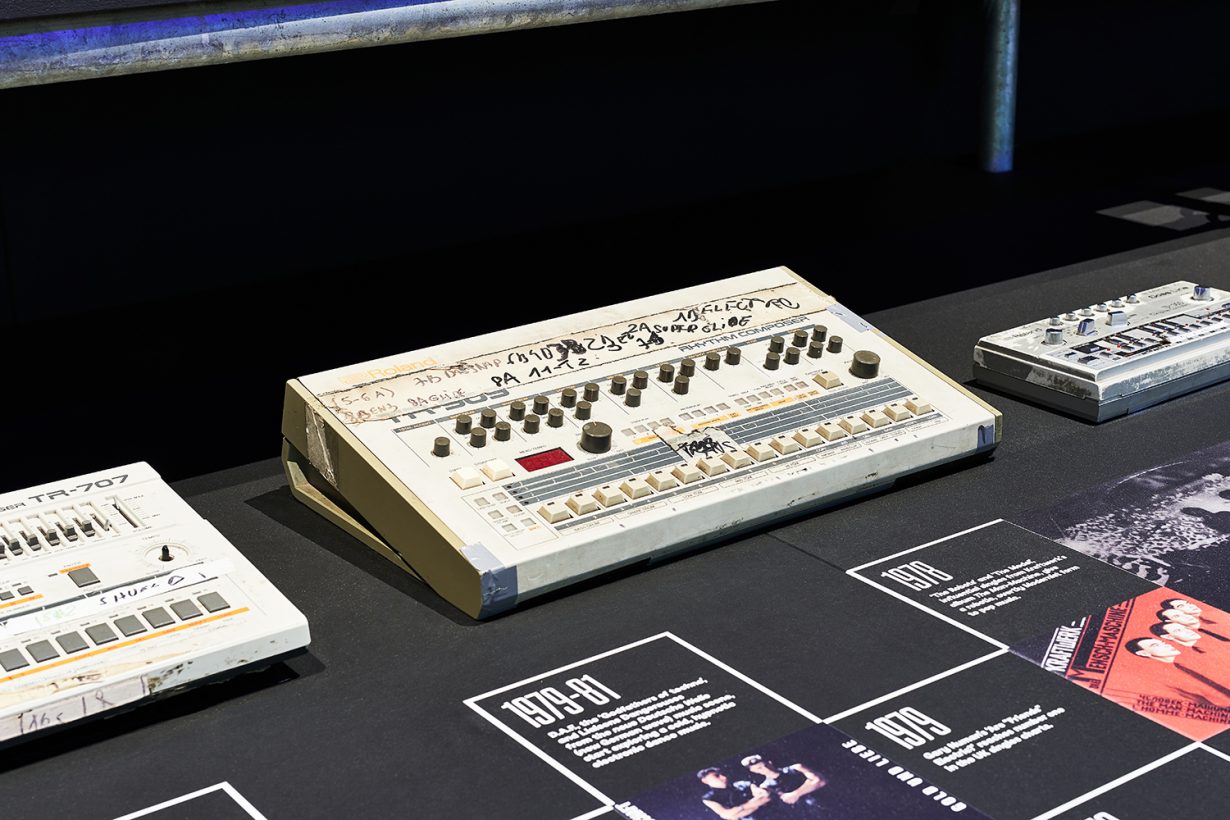

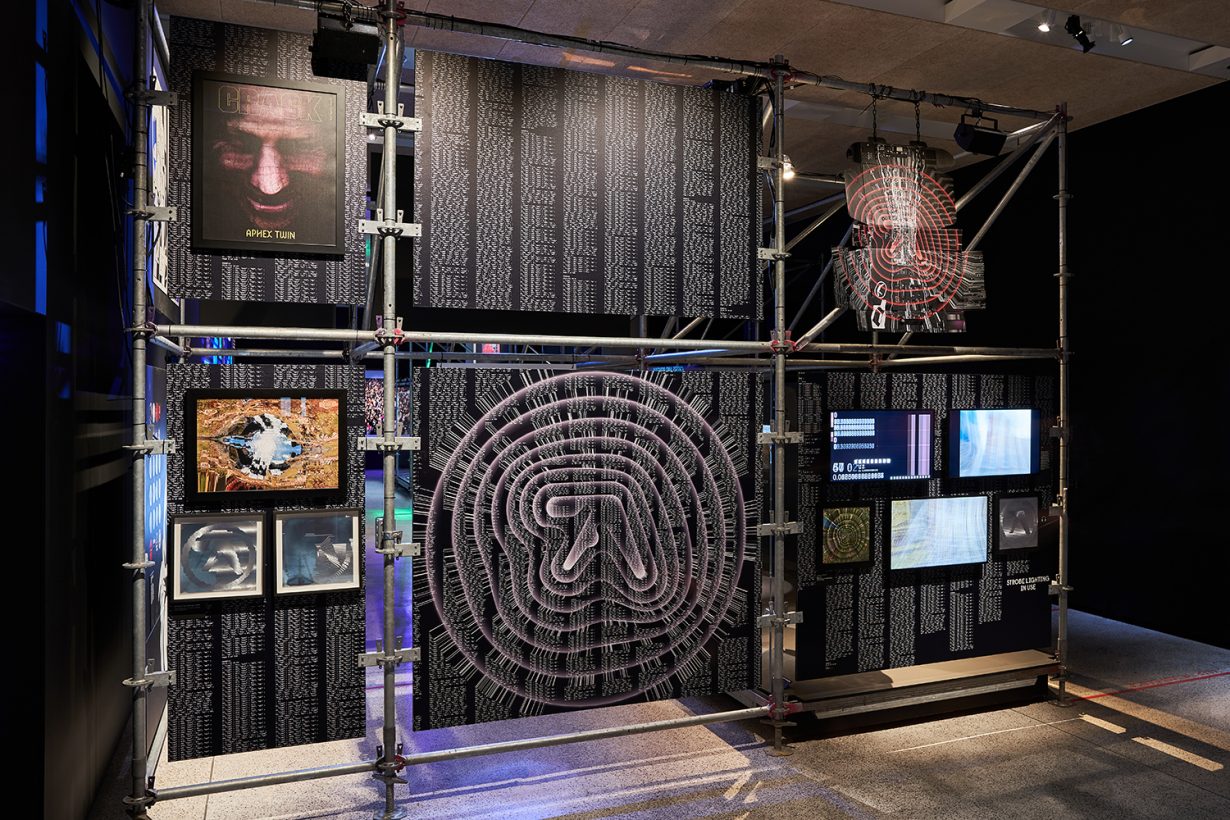

In his 2011 book Retromania, cultural critic Simon Reynolds wrote ‘I’m not sure music of any kind really works in a museum…’ His criticism stemmed from his belief that the museum’s ‘decorum’ was antithetical to popular music’s energies and that, unable to provide an authentic listening experience, music exhibitions relied on the ‘ancillary’ stuff: the instruments and ephemera. Electronic does place these on display. You can see the Roland TB-303 and French composer and producer Jean-Michel Jarre’s laser harp. But to their credit, the curators were not content to let these objects stand merely as artefacts from the recent past but as works of art in themselves. For example, Jarre’s Imaginary Studio allows the visitor to imagine the process of creation more easily than if the sheet music, books and instruments were simply lined up.

Music exhibitions have evolved since Reynolds’s disappointing encounter with the British Music Experience. Sound is still for the most part complementary. The main curatorial approach remains telling the story of music’s past, present and possible future through its visual and material culture. But interactivity, which plays a bigger part in music exhibitions than in their visual arts counterparts, might be under threat with COVID-19.

When art museums closed, exhibitions were either moved online, often in the form of curator-narrated video tours or postponed. But now that cultural institutions are cautiously reopening, directors must consider questions for which only time will bring answers: can they reassure the public that museums are safe to visit? How will blockbuster exhibitions accustomed to heavy footfall manage with reduced capacity, in order to comply with social distancing? What do people even want from art in the wake of a pandemic?

A recent US study revealed that for many respondents, with a vaccine as yet unavailable, it would take increased cleaning, reduced admissions and mandatory masks to get them to attend museums in person again. And when they do return, most respondents want ‘more fun’ and ‘distraction and escape’. Electronic offers some clues as to how the ‘blockbuster exhibition’ – no longer able to draw in blockbuster crowds to generate hype – might function in a post-pandemic future.

Masks are mandatory, capacity is reduced, regular ‘cleaning slots’ are scheduled, there are no touchscreens and you must bring your own headphones or reserve a pair. The lack of touchscreens removes an aspect of interactivity that music exhibitions often rely on to ‘engage’ visitors. But one COVID-19 safety measure inadvertently provided an unexpected source of interactivity and authenticity: plugging my headphones into the LCD screens recalled a more personal, intimate experience of listening to music and watching films.

Electronic constantly anticipates the difficulty of immersing oneself and forgetting about COVID-19 when the experience itself is dictated by the pandemic. In a corny but self-aware response, it amalgamates the safety measures into the show. ‘KEEP THE DIST-DANCE’ is printed on the floors. Booths dedicated to Detroit, New York, Chicago, Berlin – cities that pioneered sub-genres such as House and Techno and grew underground scenes that preserved the culture – are labelled ‘Capacity: One’.

While these days, you never slough off COVID-19-related paranoia entirely, there are moments where near total (but temporary) immersion occurs. Nøtel (2015), artist Lawrence Lek’s audio-visual collaboration with Kode9 drops the viewer into a virtual reality advert for an eerie, futuristic ‘hyper-luxury’ hotel without the need for a VR headset.

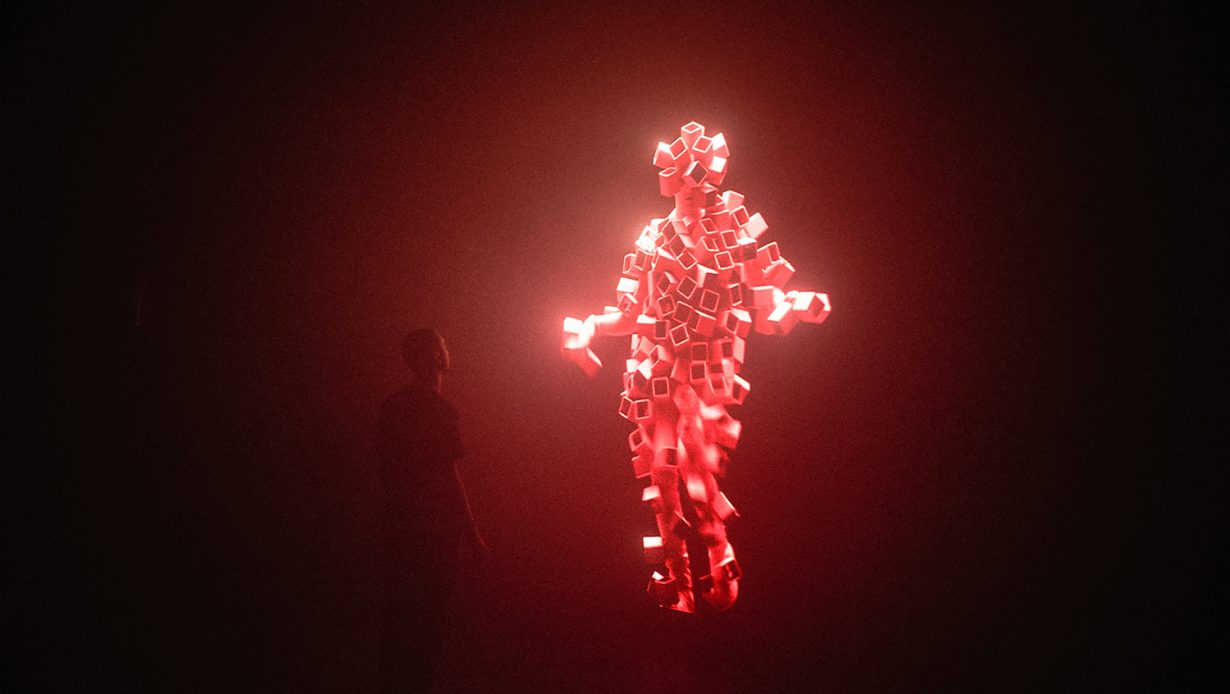

But if this sounds solitary and antithetical to the communal spirit of raves, the culminating exhibit by Marcus Lyall and Adam Smith, The Chemical Brothers’s show designers, gets delightfully close to providing a live show experience. The smoky, incense-filled room featuring the concert visuals for The Chemical Brothers’s track ‘Got to Keep On’ (2019) and intense strobe lighting, gives visitors permission to lose themselves, if only for a moment. It’s a winking acknowledgement of the surreality of these times.

Aida Amoako is a writer and critic based in London.