Rory Pilgrim and Helen Cammock are among an increasing number of UK artists focusing their practices on care work. Is this symptomatic of a welfare system in collapse, or something more hopeful?

The opening refrain of artist Rory Pilgrim’s Turner Prize-nominated oratorio RAFTS (2022) has taken up residence in my head these last few weeks: “Safe, only safe I feel / When free, free to truly be / When rain falls slow / Around”, singer Declan Rowe John’s graceful voice lilts alongside the simple strums of Pilgrim playing the harp. The lyrics speak to a sense of quietude, of moments with no expectations in which one can simply be oneself. As the song reaches a crescendo, Rowe John is joined by an orchestra and choir as she intones, “For it’s time to figure out / To figure out how to stay around / So we can dream aloud / Dream aloud / And squeeze it / And breath [sic] it / Alive, alive, alive”. The song, titled Tomorrow’s Gentle Rain, is the first composition in the hour-long RAFTS, a videowork that has also been translated into a onetime live performance and installation of the same name. The symphonic work is vulnerable and hopeful as it depicts – in seven original songs interspersed with stories and poetry – metaphoric reflections of emotional and personal vulnerabilities by the artist and their various collaborators, including musicians and members of social-work organisations. In another song Pilgrim’s frequent collaborator Robyn Haddon croons, “So release it, release it / Don’t leave it, don’t leave it / And don’t take fires on board”; these symbolic lines encourage the listener, with their own personal experiences of ‘fires’, to place themselves within the music and heed such warnings.

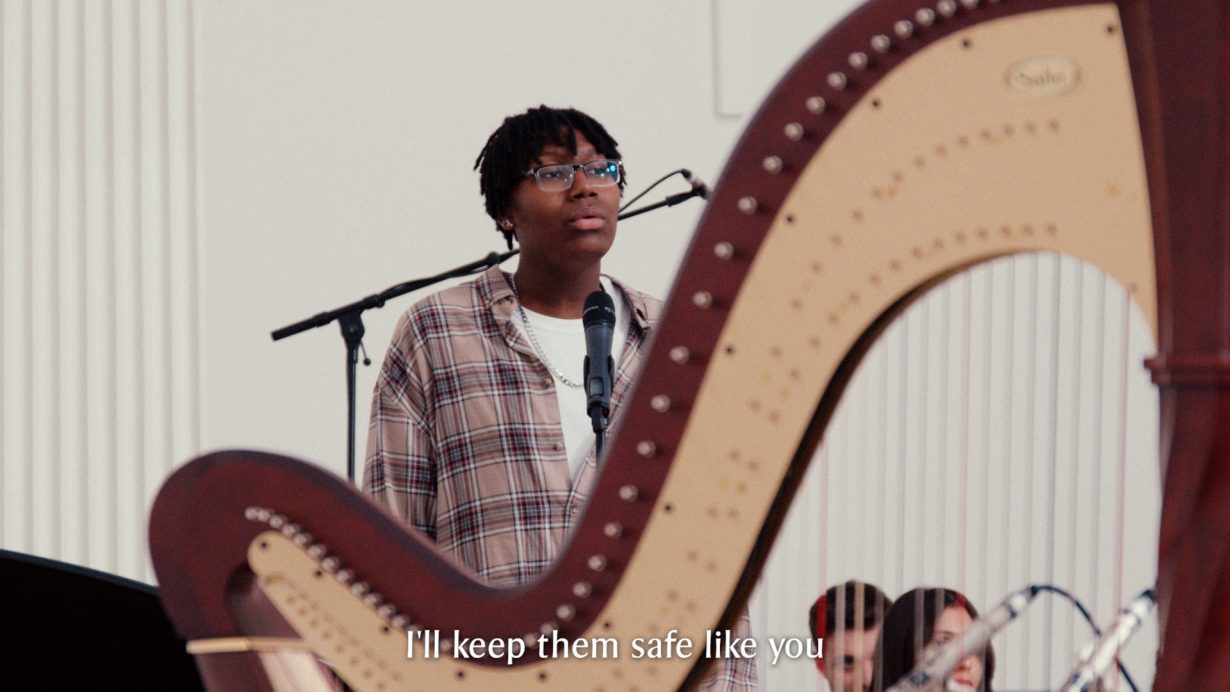

The rafts, which appear lyrically and visually in drawings throughout the work, symbolise a system of support that might be precarious, but one that stays afloat and “takes us somewhere”, rather than remaining metaphorically stagnant, as Pilgrim tells me. Pilgrim traces the early origins of RAFTS to a significant breakup, and the work’s collaborative and sympathetic nature feels like a much-needed embrace for the emotionally exhausted, offering a compassionate personal connection and testifying to the importance of interpersonal relationships as networks of support and care: “So just bring me your flowers / I’ll keep them safe like you”, Kayden Fearon sings in Flowers.

For Pilgrim, who has been a caregiver to a terminally ill person and whose parents are carers by vocation (in ministry and different-needs education), sustenance from and for a community has been a formative part of their life. Pilgrim approaches the idea of ‘care’ as a notion informed by the junctions between feminism, activism and social engagement, but one ultimately resting on a sense of compassion. Pilgrim’s emphasis on providing and facilitating a space for that within their artistic practice attests to a growing mobilisation within British contemporary art, in which some artists have visibly taken on a caring impetus and used their platforms to highlight the systemic failures of social welfare and care by creating art that responds to this breakdown with their own socially engaged projects.

The British welfare state has been in crisis since the introduction of neoliberal policies in the latter half of the twentieth century. Margaret Thatcher’s leadership during the 1980s initiated a regime of austerity and mass privatisation that continues to influence policies today. Following the 2007–08 global financial crisis the UK government implemented austerity policies that deliberately sought to minimise the welfare state in an effort to reduce the government budget deficit. Pilgrim tells me that in the wake of this crisis, which took place during their early twenties, they “became fixated on thinking about care in relation to economics”. In response to spiking unemployment rates across Europe and in particular Spain, the artist developed a live musical performance piece called Care (2012), presented in Madrid. The work featured performers lamenting that their desire to care for others was limited by dwindling bank accounts and emotional exhaustion. One says, in Spanish, “I’m worried about humanity… that those concerned with materiality just want more and more and more.” Back in the UK, austerity policies were implemented to save the economy, but the effect has made the act of asking for or admitting to the need for care shameful, altering society to the extent that many Britons have become convinced that such matters shouldn’t concern the state, that they are for the individual to resolve. This very real shunning of what should be a common concern of caring for one another, in favour of productivity and economic value, has resulted in a sort of state-sanctioned callousness that artists like Pilgrim, Helen Cammock, Ilona Sagar, Grace Ndiritu and collectives Gentle/Radical and Hospital Rooms are attempting to counteract by returning ‘care’ to the public sphere through art, exploring its many definitions and meanings in its seeming absence within the government.

RAFTS was first presented in the 2022 exhibition Radio Ballads at the Serpentine Galleries, London. The exhibition came out of a two-year project of the same name, for which artists Pilgrim, Sonia Boyce, Sagar and Cammock were commissioned to work with ‘social workers, carers, organisers and residents’ of the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham to ‘explore stories of labour and who cares for who and in what way’. Like Pilgrim, Cammock (who shared the 2019 Turner Prize with Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Oscar Murillo and Tai Shani in a gesture of ‘commonality, multiplicity and solidarity’ in the face of a politically fracturing Britain) has direct experience of the exigencies of looking after others, having spent ten years as a social-care worker in England earlier in her working life.

One of Cammock’s first jobs in social work was at a centre where she specialised in working with families and local communities. “That was the beginning,” Cammock recalls, “of being in a setting that spoke to everything that I felt emotionally, socially, politically, and about how to care and be cared for.” However, national cuts to welfare programmes during the 1990s affected her job: Cammock tells me that towards the end of her career in social care she was told by her boss to take a vulnerable young teenage girl to a police station but to avoid taking her inside, as doing so would mean social services would have to pay for a place for her to sleep. If the police took the girl inside the station themselves, they would be responsible for the lodging. “It got to a point where I thought, I can’t work within these parameters. I refuse to.” This realisation led her to think about working “with people in a different way” that brought her to art.

Cammock’s film Bass Notes and SiteLines: The Voice as a Site of Resistance and The Body as a Site of Resilience (2022) organises and documents group sessions with care receivers and caregivers from a charity called Pause – which works with women who have had (or are at risk of having) a child removed from them – as the group of woman sing, dance and compose a song together. Most of the women are not professional singers, nor do they seem to know one another very well, but by making an effort to sing in front of each other and knowing strangers will later view the videowork, they demonstrate a willingness to share their vulnerabilities. They also express to the camera their personal struggles with mental health. One caregiver admits that she witnesses and absorbs a lot of sadness in her profession, and though that in turn affects her own mental wellbeing, she has been trying to give herself time and space to reflect on and accept this anguish. Cammock relates these meditations to moments of silence between song, speech and other miscellaneous sound, where silence symbolically acts like the absence of care, or what she refers to as a “numbness”. In the video, Cammock’s voice speaks over moving images of London: “And we discussed what music and what sound can do to this numbness, to bury and furrow the notes that allow a seepage of connection. To joy, pain, remembrance. They enable a wholeness to be felt in these moments, even if only in these moments.” Bass Notes and SiteLines advocates for the real and metaphoric moments of silence just as much as it does moments of sound; ultimately one can’t be truly appreciated without the other.

Cammock continues to engage in social work, but she explains that being an artist affords her a “fluidity” and “risk-taking” that was impossible in her former career. “Artists have been working in ways that social workers would always have wanted to,” she tells me. “The systems within which social care offers care have become more impoverished, and artists have become more integral within those systems – by coming in, for example, with projects that have been funded by the arts [and in the case of Radio Ballads, local government] that they can then bring into particular areas of social work.” In doing so, those artists are making care a more visible concern in the face of an increasingly privatised welfare state and beyond the secretive realms in which it might usually occur. Cammock’s work proposes that care, caring for others and for oneself, can happen at all times. She says it’s about “being able to see and be seen, being able to hear and be heard”. Pilgrim echoes this sentiment, as they tell me that care “can happen in many ways, but inherently it is something that should already be in the world”.

The ability to be cared for or to offer care also depends on the ability to communicate. In their work, Pilgrim and Cammock often turn to music as an alternative way to communicate, offering what Cammock calls a “liminal space between word and meaning”. With elements such as the group singing sessions and Pilgrim’s earnest songs, Pilgrim and Cammock facilitate moments of vulnerability, celebrating them in their unwieldy complexity and, through sharing, start to unpick notions that needing care is a locus of seclusion and shame. Both RAFTS and Bass Notes and SiteLines feel like a musical call and response between artist and viewer, caregiver and care receiver – a “reciprocal dialogue”, as Pilgrim refers to it, that might go on to affect the viewer’s life, as Cammock hopes of her practice. These articulations and gaps in the works, in which Cammock and Pilgrim express their own and their collaborators’ sensitivities and vulnerabilities, in turn gently encourage us to feel comfortable with our own emotional states.

Perhaps, as Cammock notes, the increasing presence of artists in care work is not simply a symbol of a declining welfare system, but a chance for new forms of support. These artists’ practices, in their social work-oriented collaborations, present alternative models of community care that directly impact those involved, and perhaps those viewing the completed artworks, by appealing to the mutual need for kindness. There’s a real joy in Cammock and Pilgrim’s works undeterred by their accounts of struggle; in fact, these depicted vulnerabilities augment the mirth: at the end of BassNotes and SiteLines, we see the women’s newfound ease with each other, and RAFTS’s swelling symphony imparts an emotional sense of excitability and wonderment for life in general: “I think to create space for such joy is one of the most caregiving things you can do,” Pilgrim says with a smile.

Rory Pilgrim’s RAFTS is on view in the Turner Prize 2023 exhibition, at Towner Eastbourne through 14 April. The winner of the 2023 Turner Prize will be announced on 5 December

Helen Cammock: I Will Keep My Soul can be seen at the Rivers Institute, New Orleans, 14 October – 17 December