Transforming information into aesthetics, Sahin explores the friction between a macro and micro view of history and of human life, both forever intertwined

Save for a few wisps of cloud, it is a clear day. Viewed from a high vantage point, the sea shimmers and the curls of each wave can be seen in high definition. Where it meets the coastline, there is lush greenery, a town of uniform white buildings and roads slaloming between them. A grid of blue lines overlays the image, the squares modulating with the terrain. This largescale wallpaper work adorns one wall of Rifle in the Closet, Kurdish artist Cemile Sahin’s exhibition at Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden. It’s a pretty picture, with a sugary taste for colour and lighting.

But the high viewpoint suggests a more complicated relationship between the viewer and the landscape: we look at this 3D digital render of the city like a bird of prey, only the gridded blue lines and a digital reticle of green and red that hones our attention on one particular building suggests the eyesight of something altogether more mechanical. The exhibition booklet informs that this is the Palais de Rumine, at the heart of Lausanne. The Swiss city is significant to this show on two fronts: it is part of ‘drone valley’, an industry moniker for the region between Lausanne and Zürich as the world’s centre of civilian and military drone development, the product of which has been used in wars spanning decades across the Middle East; and it is host to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, in which the UK, France, Italy, Japan and Turkey carved up the old Ottoman Empire and divided Kurdistan and its people between multiple countries, causing a chain reaction of ongoing political conflict and displacement of Kurds. The conflicted intersection – between power, technology and the lives they impact – is instructional for the ways in which Sahin is working today.

Born in Wiesbaden to Kurdish parents who fled the region during the late 1980s, Sahin is now based in Berlin. An avid researcher, she spends months or even years leafing through books and trawling online archives, YouTube and TikTok, following her curiosity, then finessing her ideas and sources before she’ll even begin to distil these into artworks. The finished exhibitions have certain visual hallmarks: arrangements of found or digitally produced images – often colourful, largescale and wrapping around multiple surfaces – combine with posterlike text, a sense of layering created by installing images in the middle of galleries, and interrogative videos at the centre of it all. Her works are often arranged so that you see almost everything at once, your central vision flooded, then set to work on each element. Topics also recur across exhibitions, as if to reject any idea of completeness a show might imply.

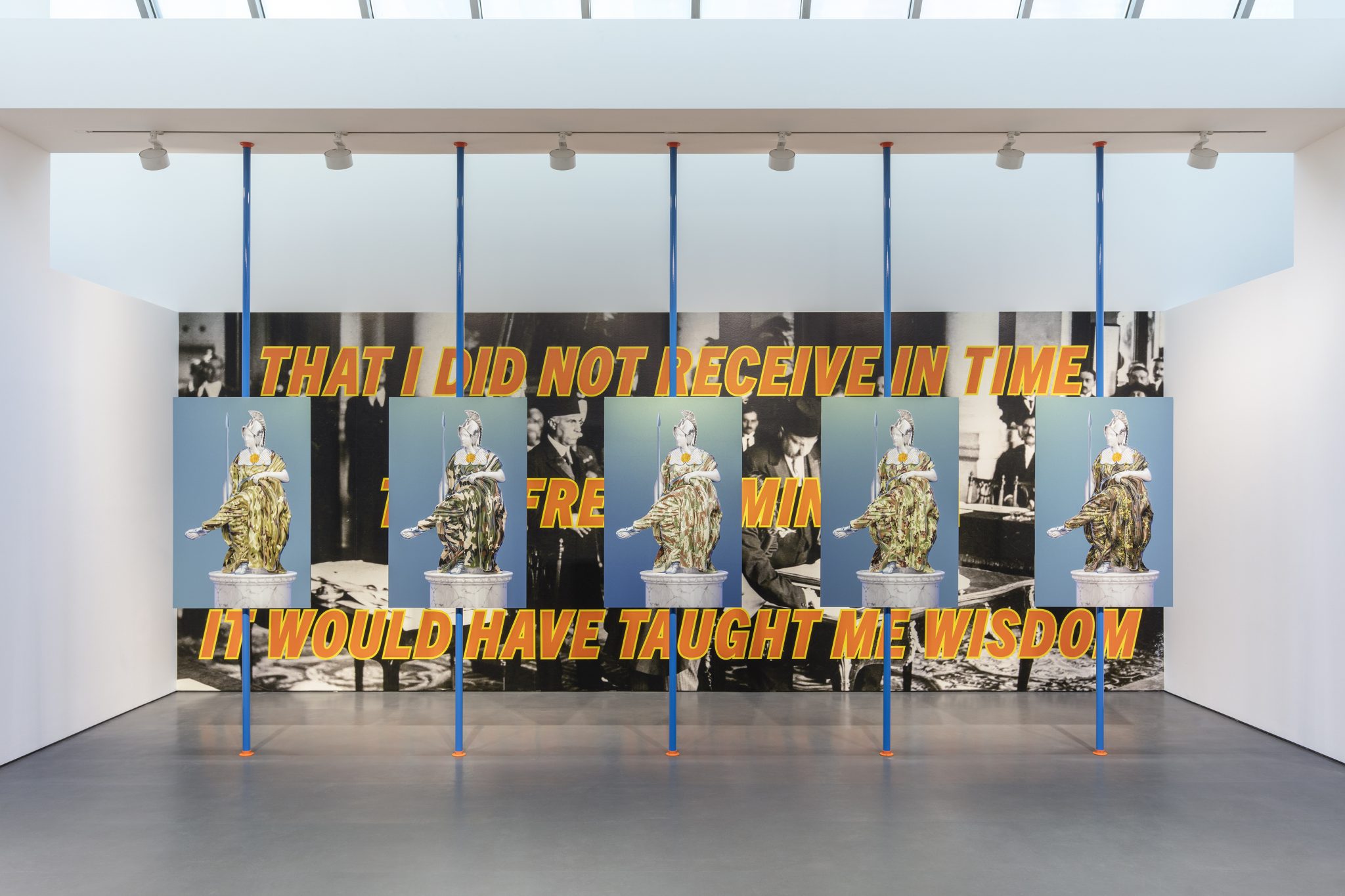

For instance: Rifle in the Closet is her third exhibition to feature Lausanne as the epicentre from which contemporary conditions in the Middle East have been dictated. Her installation Drone Valley at last year’s Lyon Biennale focused on the wall enforcing the 900km Turkish– Syrian border (the boundaries of which were marked in the 1923 treaty): blown-up images of the wall sourced from Google Maps were wrapped around the space and overlaid with block-capital text (‘THE FUTURE IS IN THE SKY / BECAUSE NATIONS THAT CANNOT / PROTECT THEIR SKIES / CAN NEVER BE SURE OF THEIR FUTURE’, attributed to modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk), a short dashcam video of a car driving up to and then crossing the border and an inflatable sculpture installed in the room that mockingly imitated a section of the wall. A later installation, It Would Have Taught Me Wisdom (2021), at Esther Schipper, Berlin, featured five UV portrait prints on glass depicting a digitally reconstructed sculpture of Minerva, the Roman patron goddess of craft and strategic warfare. Each iteration of the Minerva is clad in the military colours of the nations who were at that time undertaking military action in the Middle East. Behind the portraits, a black-and-white wallpaper image of political leaders signing the Treaty of Sèvres (Lausanne’s ‘failed’ 1920 precursor) is overlaid with orange and yellow text: ‘THAT I DID NOT RECEIVE IN TIME / THIS FRENCH MINERVA / IT WOULD HAVE TAUGHT ME WISDOM’, a quote attributed to the Prussian king Wilhelm II. Sahin’s use of text feels constantly attuned to the qualities of poetry: introducing deliberate line breaks to quoted speech or prose in order to draw emphasis to each isolated phrase; and, in this case, employing iambic tetrameter in the first line. (Sahin also happens to be a prizewinning author of two novels in German.) While the linguistic aesthetics of artists like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer will feel like obvious references for some onlookers, Sahin’s method is finetuned to her focus: she adopts words from literature and historical documentation to highlight an ambivalent poetry within them, the artistic outcome always first in service to the contexts from which it was taken.

“Art shouldn’t be so far away from society,” says Sahin, in conversation at her studio in Berlin. “I live in this world too, even if I’m sitting in my studio. I’m not some kind of genius who woke up one day and had some sort of idea. People have different talents and mine is transforming information into an aesthetic.” She is animated about film, books, nuggets of information. We talk giddily about new discoveries she has recently made while working on her next project, changes to the YouTube algorithm and handwriting styles.

She cites Chris Marker as an early influence. The French New Wave director’s essayistic approach to documentary film – and, later, his multimedia installations featuring arrangements of documentary images, video and text installed across wooden frameworks – seem a clear guide to Sahin’s contemporary engagement with such media. Where Marker’s installations were often black-and-white, gritty and melancholic, hers are luridly colourful and vertiginous in scale, and by incorporating AI and videogame technologies have uncanny tendencies.

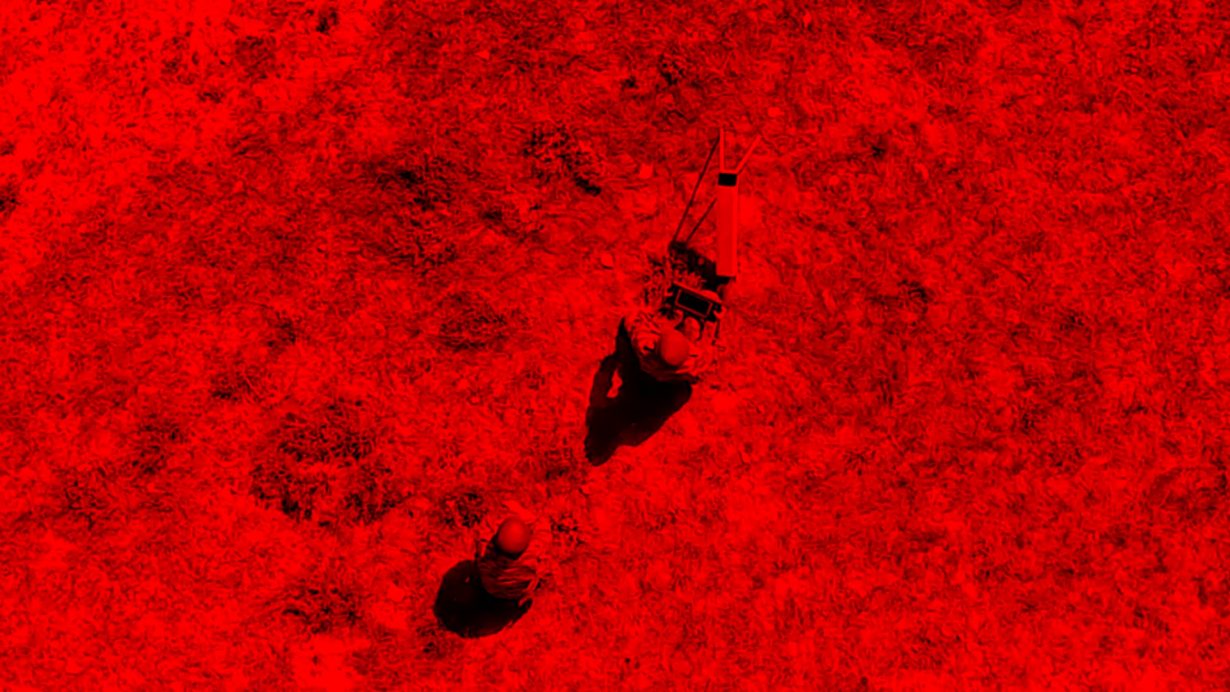

Sahin’s works also invert the monochrome radarlike aesthetic of military drone-camera images to which we may be accustomed – because the reality is in fact far more advanced. “The universities in ‘drone valley’ contribute work for the Swiss army,” says Sahin. “They develop AI simulation training for the army. They’re literally played like a game to practise.” In the video at the centre of Rifle in the Closet (a screen installed 2.75m up the wall), Sahin intercuts clips of this simulation training with drone and GoPro shots of real-world army exercises. The gamelike footage roams alongside virtual soldiers and flies over sunny hills (it could be bucolic Swiss countryside but is also, in this context, reminiscent of Kurdistan’s mountainous regions). These ‘in-game’ scenes are intercut with a digitally rendered woman reading to us passages from German philosopher and playwright Friedrich Schiller’s William Tell (1804; the titular Swiss folk hero associated with marksmanship), a quote from which also adorns the floor of the gallery space (translated from German: ‘WE TRUST IN THE HIGHEST GOD / AND DO NOT FEAR / THE POWER OF MEN’). The videogame aesthetic builds on ideas addressed in the late German artist Harun Farocki’s Parallel I–IV (2012–14), a series of films that investigate videogames as a new medium for understanding a history of imagemaking. Those films posited the self-contained, reality-mimicking worlds as a new imaginative tool for artists to create immersive environments and tell new stories. Sahin’s video explores the ways in which videogame technology might instead become an imaginative tool for malign powers to inflict future destruction, their slick aesthetics a mask for the real-world consequences of warfare.

In the introductory statement to Tomas van Houtryve’s Blue Sky Days (2013) – a series of photographs in which the artist’s small drone camera roves high above quotidian American life – he quotes an interview given by the grandson of a civilian killed by a US drone strike in Pakistan in 2012: ‘I no longer love blue skies,’ Zubair Rehman said. ‘In fact, I now prefer grey skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are grey.’ It’s a chilling admission – and one that feels relevant in Sahin’s own use of drone footage, much of which is decidedly colourful, sunny and, in isolation, presents idyllic views of their landscapes. Both van Houtryve and Sahin share a determination to point the threatening camera back on the nations who usually control them. After all, the implicit power of the drone-eye view is alarming, both in its dizzying scale and as it frequently bears the promise of violence. In Sahin’s use and ventriloquism of its images, she nods to a more widespread, and therefore disquieting, vision of the drone camera than merely its implication of violence. If photography helped accelerate the era of mass image-making, resulting in a shrinking perception of the world by making it subject to capture on camera, then it’s arguable that drone technology used in remote-controlled warfare has done something similar: the technology has expanded the size of a given battlefield to a space of almost no limitation. The complexities of this extended vantage point are alluded to by Teju Cole, who writes in his essay ‘The Unquiet Sky’ (2015) for The New York Times: ‘What was invisible before becomes visible: how one part of the landscape relates to another, how nature and infrastructure unfold. But with the acquisition of this panoptic view comes the loss of much that could be seen at close range. The face of the beloved is but one invisible detail among many.’ There is an ongoing friction here and in Sahin’s aesthetic form, between a macro and micro view of history and of human life, both forever intertwined.

So as if to counteract the dehumanising distance and aesthetic of drone footage, beloved faces are increasingly present in Sahin’s work. Four Ballads for my Father – Spring (2022), the first in a forthcoming quartet of narrative films, tells the story of a Kurdish family split between Paris and Istanbul: how their life was affected by the Southeastern Anatolia Project, a dam construction that ruptured communities in the Kurdish regions of Turkey. At one point, in a French documentary that serves as a film-within-the- film, a man recalls his former life in Kurdistan and the circumstances that led him to Paris. “I thought I wanted to be a hero, so that people would later say: he fought for the freedom of his people… But the fact is also that I am alone here. I miss Kurdistan. I want to die in Kurdistan. Not here… To a certain degree I’m still pretending to be a person I am not.” He speaks to us, though, in a voiceover; in the interview chair, he sits silent. While we listen to his voice, the footage cuts between the sitting man and a grainy handheld-camera montage of the Kurdish countryside. “Feeling a pain is one thing: you suffer,” he says. “But to describe a pain is another: you suffer and you understand why.”

This mode of emotive directing – edited from a collection of footage Sahin found in Kurdish television archives and from family records, layering Spring’s fiction with real-world sources – contrasts with the clinical, mechanical eye of the drone, reinserting human experience and presence where such kinds of military technology erase it. “Speaking about home is protective, and a really deep, sad cause,” says Sahin. “People are forced to leave. Sometimes they cannot take anything. It’s really hard for a lot of people because they clinch onto their memories: for a lot of political refugees, they went back 30 years later and everything they had in their head – how it was, their school, their house – was gone, and it became a question of whether you can ever go back at all.” It’s a concern shared by many writers, often of a similar generation, displaced and living with trauma in the wake of war – take Tamil author Anuk Arudpragasam, who in his novel A Passage North (2021) describes memory becoming ‘far harder to maintain when all the clues to that memory that an environment contained were systematically removed’.

Sahin finds a parallel in other forms of image production: “There’s almost no Kurdish cinema. For the last century there was just war in Kurdistan, people didn’t have time to make films – they just had to survive. So you have to build a whole new cultural memory and you need to start in the past. You cannot build it back entirely, but it’s important to do it. It gives people hope – for life, that something can be rescued.” With this point, the crux of her work crystallises: a drawing of attention to the operations of both historical and contemporary state power; and to remind viewers of who it impacts. Taking us from sweeping drone-eye views, down to the granular ache of loss, Sahin’s critically forensic, visually iridescent – and increasingly heartfelt – works rally in the face of an irretrievable past.

Cemile Sahin’s exhibition Rifle in the Closet is on view at Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden, through 23 July