An exhibition at Centre Pompidou, Paris, is a reminder of the artist’s cultivated air of hobbyist enthusiasm – ‘an attribute that grates as much as it charms’

For the past 40 years, Christian Marclay has been using his work to explore the afterlife of redundant technology and vintage pop-cultural imagery, and his evident affection for the material detritus of the late twentieth century – from vinyl records and dial-up telephones to comic books and B-movies – carries with it a distinct air of hobbyist enthusiasm. Over the course of this partial retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, encompassing a dozen galleries and more than 200 works, it’s an attribute that grates as much as it charms.

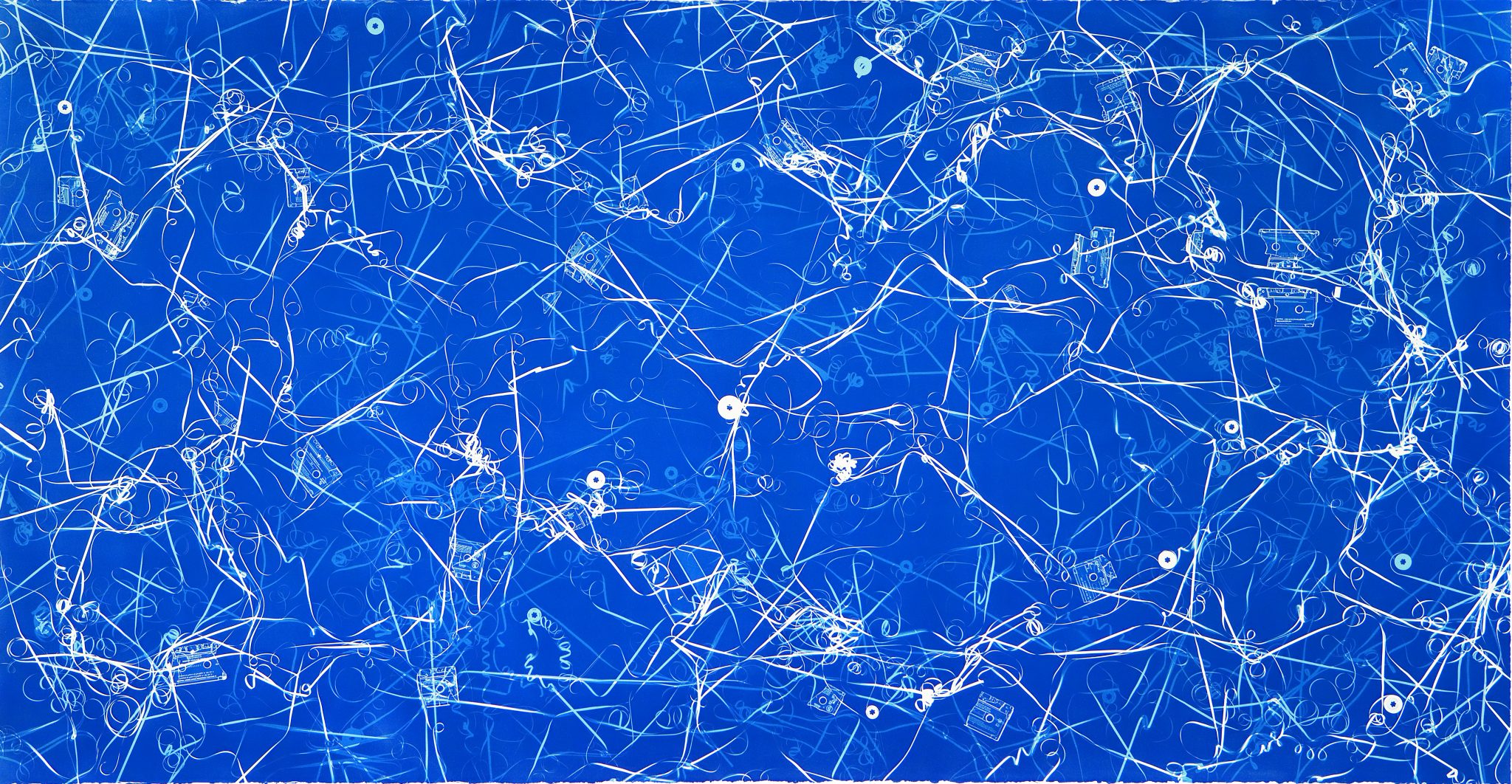

Marclay is not strictly a nostalgist: his earliest use of records and tapes as a medium predates their commercial decline. Record Players (1984), for example, is a video in which the artist scratches, wobbles or bangs vinyl LPs against each other; The Beatles (1989) takes the form of a cushion-shaped object knitted from tape ribbon pulled from cassettes of the titular group’s albums; Body Mix (1991–93) sees album covers depicting the human physique arranged on the wall in a kind of rock’n’roll take on the Surrealist game ‘Exquisite Corpse’.

While Marclay’s work has become ever more formally ambitious since, it still carries the same spirit of teenage nerdishness and late-night stoner humour. For all its technical accomplishments, even his most celebrated work, 2010’s The Clock – a 24-hour compilation of clips from film and TV in which clock faces display the actual time of the place in which the artwork is screened – can be read the same way. That work is not present here (small wonder: Marclay describes it as ‘the albatross’) but we do get Doors (2022), a new video installation that follows much the same formula: we glimpse clips from films in which characters open and shut doors, cutting to a different cinematic source every time one closes.

The one work here that presents an obstacle to judging this exhibition on its own, carefree terms is Guitar Drag (2000), a film created in response to the murder of James Byrd Jr, an African-American man who was attacked by a group of white supremacists in Jasper, Texas, in 1998. The assailants tied the stricken Byrd to the back of a pickup and dragged him at high speed over rough ground for five kilometres. According to coroners, he remained alive for at least half of the ordeal. Marclay repeated the death drive nearby, with an amplified electric guitar standing in for Byrd’s body. The grainy footage gives it the air of a home video, but the horrendous din that screams from the soundtrack denies it the comforting familiarity that marks much of Marclay’s work. Evoking a wealth of pivotal twentieth-century musical references – John Cage, electric blues, Jimi Hendrix mangling The Star-Spangled Banner – it’s as visually and sonically thrilling as it is upsetting, and tearing one’s eyes away is a challenge. Yet there is never any real crescendo: indeed, the piece appears edited specifically to defy any sense of narrative or structure, delivering its kick at gut level. For all that this show as a whole is is enjoyable, not much here feels anywhere near as vital.

Nevertheless, there’s frequently a real beauty to what we see: consider, for instance, the collage series Imaginary Records (1987–99), for which Marclay cut up dozens of old album sleeves to create entirely new combinations of typeface and imagery. In Rhythm (1997) this process gives way to a kind of archivist concrete poetry: in this instance, the eponymous title, in bold red capitals, hovers above a square photograph of cracked earth; the collage’s implied ‘rhythm’ encourages the viewer to interpret a pattern in the zigzagging lines in the patch of ground depicted in the image. Like so much here, it is fun and inventive and touchingly homespun. What the show’s more middling moments demonstrate, however, is just how easily these qualities can start to seem winsome.

Christian Marclay at Centre Pompidou, Paris, through 27 February