In an age of rentable, disposable virtualised culture, why the artworld stubbornly resists dematerialization

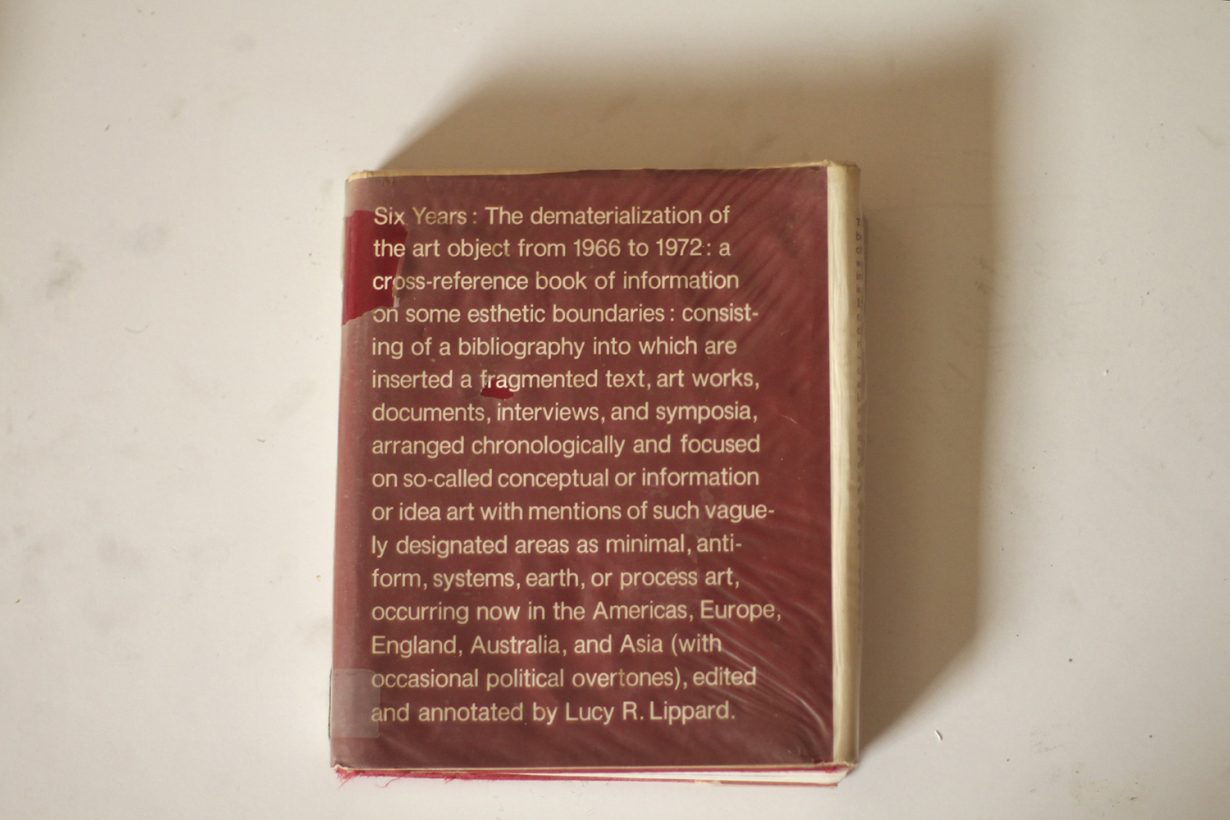

It’s a half-century since the chronological endpoint of Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object (1973), which catalogues conceptual art practices from 1966 onwards. The book ends on a melancholic note: ‘Hopes that “conceptual art” would be able to avoid the general commercialization… of modernism were for the most part unfounded,’ Lippard wrote. Plus ça change. Here’s an irony, though: today, dematerialisation is a huge cultural trend, and visual art is among the only holdouts against it.

Since the turn of the century, music, books, film and television, video games and more have divested themselves of materiality, beaming into our lives through our phones, smart TVs, e-readers, laptops, and Nintendo Switches, usually rented for a monthly fee and even when purchased reduced to data. (The very real materiality, in terms of energy costs, rare-earth elements, etc, that drives such weightlessness has been well outlined elsewhere, and lies outside the scope of this screed.) Whatever there is to be said about how this devalues, say, music and movies, encourages us to treat them as disposable, the evident trend is away from the burden of ownership – except, of course, when it comes to the devices required to make the products come to us: to access Mubi, Grand Theft Auto, Kindle books, porn, or whatever. Meanwhile, contemporary art, whose practitioners understood the virtues of getting rid of materiality before most of us were born, primarily continues to inhabit a saurian netherworld of physical objects that stubbornly resist becoming creatures of light.

There are several obvious reasons why: money, ‘aura’, the limitations and cost of the available technology. The last one is probably the most important. For a long time, the reception and acquisition of art has been tiered: collectors buy expensive one-offs, which wouldn’t be so expensive if it weren’t for scarcity value and market manipulation; those on a smaller budget who love art perhaps buy editions (which themselves can increase in value, sometimes stupidly). But I and others in the hugely expanded market of interest in contemporary art, can’t (yet) pay a monthly fee to have digital artworks of any stripe beamed into our homes, and clicked off when we’re bored of them, when we want something new, or because our friends are coming round and, honestly, we never quite got over Salvador Dalí.

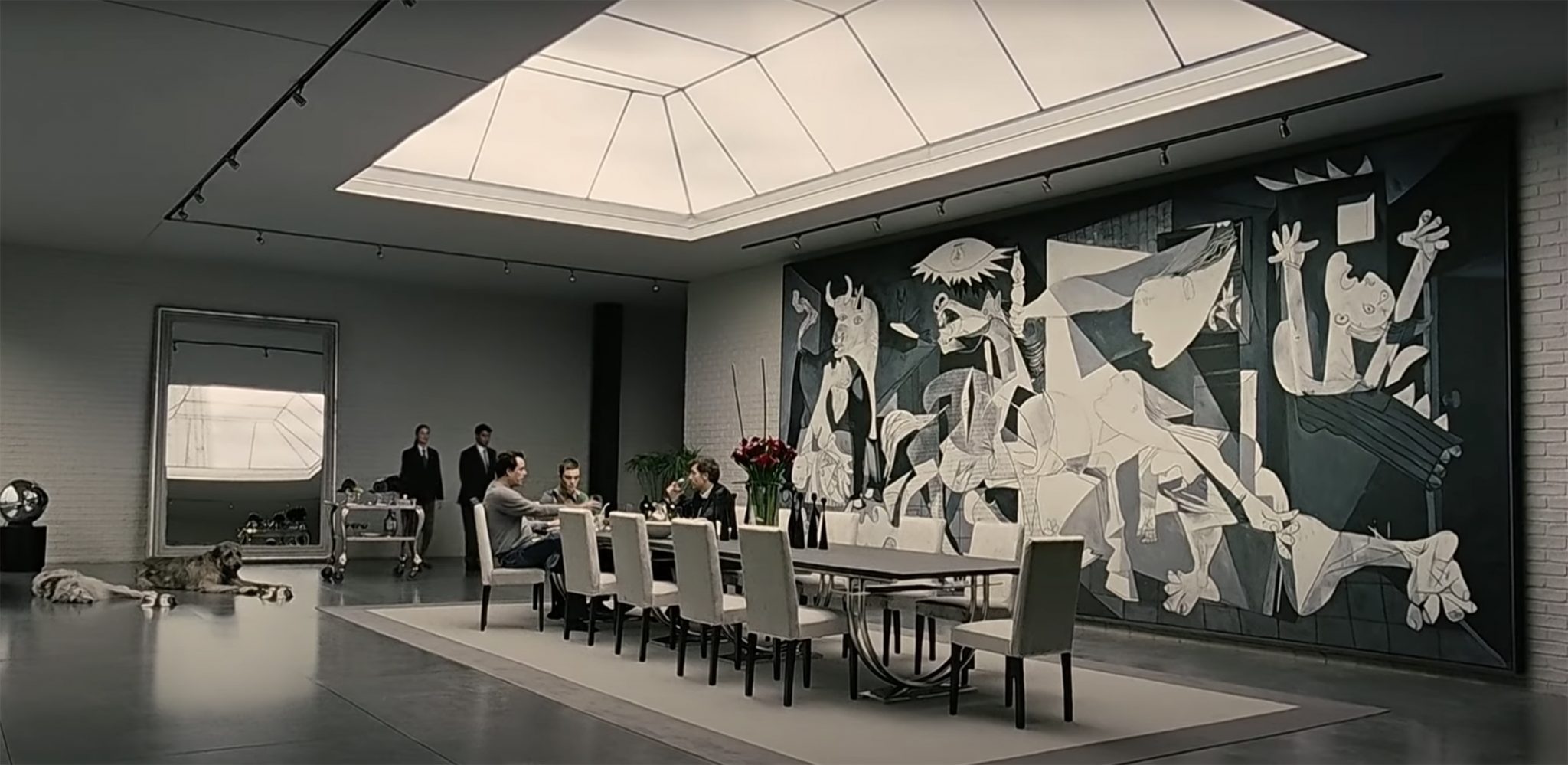

Such a technological option, whatever your ambivalence about it, wouldn’t prevent art remaining a shady asset class, in the same way that the existence of a Kindle version of Great Expectations doesn’t prevent a first edition of the same book being super-expensive. At this point down the line of possibility, the experience of art might bifurcate, broadly, into a slightly less dystopian combination of Children of Men (2006), in which one person owns all the real art, and Ready Player One (2018), where the poors – or, sorry, non-collectors – spend their time in a virtual universe. Or one in which you can go to a museum but also come home, flop on the sofa, and flick on a simulacrum of a sculpture. Or, more likely, given the residues of aura clinging to solid art objects as we’ve come to understand them, experience whatever kind of artistic practice has best adapted itself to changes in medium, to Virtual- and Augmented- and Mixed Reality and whatever other type is to come.

This is to leave aside even more speculative ramifications concerning what such a model would do to reception and attention. There’s probably a bit of time to consider it, since the artworld as it’s constituted today seems to take pride in not gearing up for such crass commercial opportunity, or even leveraging the technology that exists. Is there a decent video-art streaming service, even? No.

When, two years ago, philosopher and curator Daniel Birnbaum quit his directorship of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet to work for virtual-reality art startup Acute Art, the critical consensus, as I understood it, was that: a) he was surely being paid a lot of money to dick around with gadgets and bring in his famous artist friends; and/or b) he was a fashion victim. Since then AA, as they probably don’t call it, has worked with figures including Marina Abramovic, Olafur Eliasson, Bjarne Melgaard, Cao Fei and a fair few more, spinning out virtual reality exhibitions and projects like the startup’s eponymous app, in which you can currently access projects like Unreal City, planned as a walking tour but converted into an augmented-reality lockdown project, wherein you ‘curate an exhibition at home’ by placing floating KAWS figures or Koo-Jeong A doodles around your ‘room’ – as long as you’re staring at your phone – and looking at them in sort-of three dimensions. (Or, in my case, trying quixotically to kick the KAWS away.) It all feels a bit clunky, embryonic and lightweight, but Birnbaum, somewhere down the line, may end up having the last laugh. Or he may not, and art might instead end up claiming another, defiantly blimpish position: in a world of rentable, disposable virtualised culture, continuing to be the last brave bastion of materiality.